The parkland at Brantinghamthorpe is of interest as a good example of a modest planned landscape of the early 19th century, but of particular historical significance are the remnants of the Victorian formal gardens laid out for visits of the Prince of Wales.

Estate owners

The Brantinghamthorpe estate owned by Hugh Mason of Hull in the early 18th century passed through a number of owners until 1801 when it was purchased by Isaac Broadley (d. 1816), a Hull merchant, who was then living at Brantingham Hall. Following Broadley’s death it was sold in 1819 to Edward W. Barnard, vicar of South Cave (d. 1828). Barnard’s devisees sold the hall to Captain Richard Fleetwood Shawe (1804-72) in 1832. (Allison, Hull Gent, 49)

The hall and estate were purchased in 1867 by the Revd Sir Henry Foulis on behalf of his nephew Sir Tatton Sykes 5th Bt. (ERALS, Deeds Registry KH/236/287.) It then became the home of Sir Tatton’s brother, Christopher Sykes, who hosted a number of visits here by Edward, Prince of Wales, the first in July 1869. (Sykes, The Visitors’ Book , 84-87)

From 1889 the house was tenanted by John Edward Wade, timber merchant, who bought the estate in July 1899 following the death of Christopher Sykes the previous year. (Sewell, Joseph Armytage Wade, 24; Eastern Morning News 13 July 1899) Wade died on 28th September 1899.

Later owners included George Thorpe-Wilson c. 1905-10, Sir John Sherburn, c. 1910-1929, Arnold Reckitt 1929-53, and Mrs Dorothy Maxted (daughter of Arnold Reckitt) who lived there 1953-73. Mrs Maxted was followed by her daughter Sally and her husband Christopher Frith. The house was sold by the family in 1988 and has since changed hands a number of times.

Early history of the site

The porch of the present Victorian house is said to be dated 1567. It is evidently on the site of, and may have at its core, the Elizabethan house built by Anthony Smethley who died in 1578. Nothing is known of its setting but in 1766 when Brantinghamthorpe Hall was owned by Carleton Monkton it had modest grounds of around 8 acres (3 h.). (HHC, U DDCV/25/3 Brantingham Enclosure Plan, 1766.) It is likely that no extension to the grounds was undertaken until the hall was purchased by the Revd Edward Barnard in 1819.

Chronological history of the designed landscape

1819-31 Edward BarnardIn addition to the property acquired from Broadley’s devisees, Barnard bought land adjoining the grounds of the hall from the Athorpe family and others. A diversion of the highway from Elloughton to Brantingham was obtained in 1819 which enabled the laying out of a small park. (ERALS, HD/22) When the house was to let in 1824 it was said to have ‘an excellent walled garden, lawn, shrubberies, fish pond and plantations’. (York Herald 28 Feb. 1824) Barnard may have been responsible for much of this for Teesdale’s plan of the East Riding, surveyed 1817-18, shows no obvious parkland, but the first edition Ordnance Survey 1” to the mile plan of 1824 does. The latter plan is not clear but parkland with boundary plantations are suggested. Bryant’s plan of 1829 is clearer where the house is named as the Priory.

1832 – 67 Richard Fleetwood ShaweRichard F. Shawe (1808-72) enlarged the house in the Gothick style and extended the parkland by moving the road from Elloughton to Brantingham further south-west in 1834. (ERALS, HD/39) He was probably responsible for planting some of the clumps and single trees shown in the parkland on the Ordnance Survey map published 1855.

Shawe was one of the original members of the Royal Agricultural Society and was evidently keen on horticulture. (York Herald 18 Sept. 1872) The walled garden flourished under his head gardener, Robert Creaser Kingston (1818-95). Kingston was the son of the gardener at Saltmarshe Hall and was working at Brantingham Thorpe by 1841. (Census Returns, 1841 HO 107/1216/15; Hull Packet 2 Sept. 1842) Kingston was a frequent prize winner and judge at the principal local horticultural shows and his son, Robert Creaser Kingston, jun. (1846-72) worked in the Royal Herbarium at Kew Gardens. (Hull Packet 2 Sept. 1842, 26 May 1843, 12 Sept. 1845, 16 July 1852 ; Journal of Botany, NS 1 (1872), 224)

The gardens were described in 1841:

1867-89 Christopher SykesThe whole cannot stand on less than four acres of land, which are laid out in a most judicious and elegant manner. There are four hot houses in the first kitchen-garden, in which are figs, nectarines, and vines against the wall whilst the floors are filled with early fruits of various kinds; the whole are heated by means of hot water conveyed through large iron pipes.

The dahlia or centre walk is very handsome, and the productions of the garden very fine. In the second kitchen garden is the forcing ground, asparagus beds, melon, and pine pits, the latter in every stage of growth to maturity.

The shrubbery and flower garden, of more than two acres, is very beautiful. The rose walk from the first kitchen garden, the climbing roses creeping over a large frame work, and the aviary with its canary birds; goldfinches and turtle-doves are all very pretty, but the grand attraction is an elegant conservatory with many of the rarest and finest plants.’ (Allen, The Stranger’s Guide, 67-9)

On taking over the estate in 1867 Christopher Sykes largely rebuilt the house in time for the first royal visit in 1869 and made substantial changes to the grounds. It was stated in 1879 that Brantinghamthorpe ‘as it is now is a very different place from what it was when Mr Sykes first bought it from Captain Shaw … the park, the pleasure-grounds, the gardens, the approach to the house … have been more or less transformed under Mr Sykes’s judicious and indefatigable administration’. (Beverley Guardian 13 Sept. 1879). A lodge was built on the Elloughton to Brantingham road (New Road) at the south-west corner of the park and a long drive led up to the hall.

The changes to the gardens were planned and supervised by James Craig Niven, curator of Hull Botanic Gardens 1853-81. He was seemingly responsible for the terrace to the south of the house, described in 1899 as being ‘enclosed by stone retaining and parapet walls’, and ‘in two tiers, the upper one being neatly graveled with grass verges, and the lower one embracing a beautifully level lawn, interspersed with flower beds’.

From the terrace the lawn extended to, and included, the tennis court, and ‘thence it ascends by a flight of stone steps to the Eastern Lawn, which opens out expansively to the rear of the house, and towards the middle of which stands the Conservatory. The rear of the house is beautifully shrouded by ancient yews, and the lawn is well sheltered by beech and other timber trees.’ (HHC, U DDCV/25/46)

The walled kitchen gardens were described in 1899 as ‘large, well-stocked, and productive’. The heated glasshouses included early and late peach houses, early and late vineries and a rose house. There were also ‘adequate potting sheds, forcing houses, frames, and pits’. (HHC, U DDCV/25/46)

The tunnel marked on the 1891 plan (below) runs from the house under the Eastern Lawn to give access to the Stables and Coach House. Statues and other garden features were scattered throughout the grounds – a French leadwork figure and a French sundial were featured in an article on Brantinghamthorpe in Country Life in 1905. This well-illustrated article barely mentions the park and gardens.

An avenue of Wellingtonias leading from the Eastern Lawn via a wicket gate was known as ‘the Royal Walk’ because it was planted by the Prince and Princess of Wales and various members of the Royal Family. The walk led to a summer house ‘named by the Duchess of Edinborough [sic] “Melovoid” or beautiful view’. (HHC, U DDCV/25/46)

20th CenturyThe evidence from maps and images suggests that there were no major changes to the grounds in the 20th century, although the southern cormer of the park was cut into by the new route of the A63 and the lodge demolished.

In 1987 it was noted that, ‘the mature park trees and clumps have been recently enhanced by strategically sited tree planting schemes established with the aid of the Countryside Commission’. (Humberside Property Guide, 29 May 1987). A grandson of Sir John Sherburn who visited Brantinghamthorpe Hall around 2001 recorded that the ‘glasshouses were in ruin and walled kitchen garden was full of weeds’. (Wales, ‘Reminiscences of the Rev. Vernon Clarke’, 12)

Location

Brantinghamthorpe Hall and its park are located immediately south-east of Brantingham village, north of the A63, about 12 miles west of Hull and 2 miles north of Brough.

Area

Gardens, park and woodland about 75 acres (30.5 ha), of this the open parkland 53 acres (21.5 ha).

Boundaries

The park is bounded on the south-west by the A63 and the now disused section of the road from Brantingham to Elloughton (formerly New Road). The boundary to the south-east is the parish boundary with Elloughton and the Scarborough Wold Plantation, to the north the drive or lane from the hall to Brantingham village, and to the east the western boundary of fields on the Wolds slope.

Landform

Brantinghamthorpe Park lies on the west facing slope of the Yorkshire Wolds. The land rises west to east from 30m to 80m AOD, rising most steeply to the east of the hall. The hall and gardens lie at the bottom of the chalk slope. Chalk (Ferriby Chalk Formation) forms the bedrock of the hall site, gardens and parkland to the north east, and a grey calcareous siltstone (Brantingham Member) the bedrock of the parkland to the south east. The surface deposit is alluvium throughout.

Setting

The parkland is in East Riding Landscape Character Area 12, Yorkshire Wolds Sloping Wooded Farmland. Arable fields, pasture and woodland on the west face of the Wolds is the setting for the parkland to the east, south-east and north. Immediately to the south-west, however, is the busy A63, extensive market gardens and the large villages of Elloughton and Brough, and in the distance the broad River Humber.

Entrances and approaches

The former approach from the southern entrance to the park off the road from Elloughton to Brantingham was closed when the present A63 was built c. 1970, the lodge demolished and access ended.

The hall and parkland are now approached via a roadway commencing at the southern end of Brantingham village and entering the grounds through an elaborate gateway. The gateway and adjoining garden walls are listed grade II. Probably erected in the late 1860s and possibly designed by George Devey.

Principal Buildings

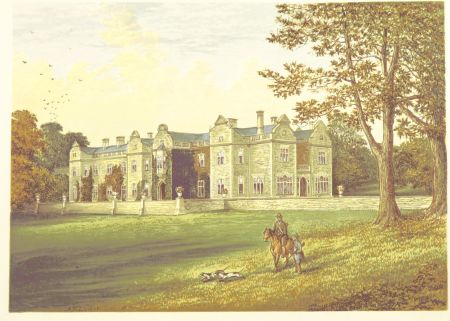

Brantingham Thorpe Hall Listed Grade IIElizabethan house, altered or rebuilt in the late 17th-early 18th century, and greatly enlarged in the Gothick style in the late 1830s. The architect George Devey was employed 1868-83 to transform the building into the present rambling house in a mid-17th century style, built of local honey-coloured limestone with an array of shaped gables and mullioned windows. (Pevsner & Neave, Yorkshire, York and the East Riding, 339-340)

Gardens and pleasure grounds

The layout and a number of features such as terraces, walls and steps remain of the once lavish Victorian gardens. On the west side of the hall there is only a terrace with retaining walls from the splendid terraced gardens with ornate formal flower beds and numerous urns and statues that were laid out by J.C. Niven to impress Royal visitors in the later 19th century.

The east terrace and Lawn to the east of the hall remain but without the large conservatory and many other features. Map evidence suggests that the wooded area, or shrubbery with circular fishpond, that existed in 1855 to the south of the entrance drive, survives, as do the woodland areas between the eastern lawn and the stables and to the east of the walled kitchen gardens.

Kitchen Garden

There was a walled kitchen garden in 1824 which may have been on the present site to the north-east of the hall. Here the once impressive walled gardens covering about 4 acres, described above, are now derelict. The walls and remnants of glasshouses and associated buildings remain.

Park

The present layout and character of the parkland with its grassland, clumps of trees, and border plantation to the south-east is much as it was in the mid-19th century.

Books and articles

James Allen, The Stranger’s Guide to Ferriby, Welton, Elloughton and South Cave, 1841

J. Allibone. George Devey, architect, 1820-1886, 1991

K. J. Allison, ‘Hull Gent. Seeks Country Residence’ 1750-1850, 1981

‘Brantingham Thorpe, Yorkshire’ Country Life 11 March 1905, 342-6

J.G. Hall, History of South Cave, 1892

Journal of Botany, NS 1 (1872)

M. Sewell, Joseph Armytage Wade, 1996

C. S. Sykes, The Visitors’ Book, 1978

N. Wales, ‘Reminiscences of the Rev. Vernon Clarke’, Craic: The Magazine for Great Salkeld & Area, 8, Winter 2012

Primary sources

Hull History Centre (HHC)Brantinghamthorpe Hall Estate Sale Particulars 1899 U DDCV/25/46

East Riding Archives and Local Studies (ERALS)Deeds Registry

Highway Diversions (HD)

Newspapers

Beverley Guardian

Eastern Morning News

Hull Packet

Humberside Property Guide

York Herald

Maps

Brantingham Enclosure Plan 1766 Hull History Centre U DDCV/25/3

T. Jefferys, Yorkshire, published 1772 & 1775

H. Teesdale, Yorkshire, surveyed 1817-18, published 1828

A Bryant, East Riding surveyed 1827-8, published 1829

Ordnance Survey maps published 1824 -2012.