The designed landscape at Goldsborough has developed over the last 500 years by its owners taking advantage of its natural beauty and favourable topography. The de Goldsburgh family held the manor from the mid-12th century and utilising an extensive wood to the south, created a deer park by the early 16th century. Later owners in the 18th century were inspired by the leading designers of the day, including possibly Stephen Switzer in the 1730s. Daniel Lascelles, its wealthy owner from 1762, sought the advice of two landscape designers, Richard Woods and Thomas White, soon after his acquisition. Both men though produced relatively modest proposals with only minor changes immediately around Goldsborough Hall. However the partially extant walled kitchen garden with its hothouse built in the wall is almost certainly to the design of Woods.

After Daniel Lascelles’ death in 1784, Goldsborough became part of the estate of the Earls of Harewood and was often occupied by members of the Lascelles family. In many cases, this was the heir to the Harewood earldom and Goldsborough provided an opportunity for them to shape its designed landscape. The last of these was Viscount Lascelles, later the 6th Earl, whose wife, Princess Mary, was a keen gardener. Her influence on the grounds adjacent to the hall remains to this day. In the wider landscape, all the parkland and most of the woodland that were in-situ in the 18th century remain and provide an important setting for the Grade II* listed Goldsborough Hall.

Estate owners

In 1086, Goldsborough was part of the estate of Ralph Paynel, with Hubert as his tenant. By the middle of the 12th century, the de Goldsburgh (or Goldesburg) family, thought to be descendants of Hubert, held the manor of Goldsborough for the Paynel family (Farrer 1914, 394-5). The first of these to be mentioned in 1166 was Hugh, who had three sons, Richard, Herbert and Adam. Richard’s son, Richard, was the heir to the estate in 1230 (ibid, 395). Goldsborough remained with this family until c. 1599 when Sir Richard Hutton started to acquire the parts of the estate that had been split due to disputes over inheritance.

When Sir Richard Hutton’s grandson, also Richard, died in 1680, the estate devolved first to his daughter, Elizabeth, who had married Philip Wharton and then to his granddaughter, Mary. Mary Wharton married her mother’s cousin, Robert Byerley, in 1692. Robert and Mary’s five adult children had no heirs, so the last surviving one, Elizabeth, decided to sell the estate in 1759. This was acquired in 1762 by Daniel Lascelles, who already owned the nearby Plumpton estate. It remained with the Lascelles family (Earls of Harewood) until 1951, when the Hall was sold to Boyer family and the wider estate was put up for sale the following year. Following the conversion of the hall into a nursing home in the 1980s, it was sold together with its immediate grounds to the current owners in 2005.

Key owners and tenants responsible for major developments of the designed landscape and dates of their involvement:

Richard de Goldeburg c. 1268 – ?

Sir Richard Hutton c. 1599 – 1639

Robert and Mary Byerley 1692 – 1714?

Robert Byerley junior c. 1723 – 9?

Elizabeth and Ann Byerley c. 1735 - 55

Daniel Lascelles 1763 – 84

John and Frances Douglas (née Lascelles) 1797 – c. 1802

Henry Lascelles (later 3rd Earl of Harewood) c. 1823 – 44

Henry Lascelles (later 4th Earl of Harewood) 1848 – 57

Sir Andrew Fairbairn 1871 – 8?

Henry Lascelles (later 6th Earl of Harewood) and Princess Mary 1922 – 30

Unless otherwise stated, all archive references are from West Yorkshire Archives Service, Leeds.

Early history of the site

In 1066, Goldsborough had 8 carucates (c. 480 acres) of arable land but this had reduced by half by 1086. In addition, there was woodland of 12x4 furlongs (1.5 x 0.5 miles, c. 480 acres) and the settlement had seven households. Ralph Paynel held it with Hubert being his tenant (https://opendomesday.org/place/SE3856/goldsborough/, consulted 21 February 2024). By the mid-12th century, the family of de Goldeburg (Goldsborough) were the tenants and on the 12 October 1269, there was a grant of free warren to Richard de Goldeburg in his demesne lands in Goldsborough (PRO 1906, 125). In 1292/3 the grant of free warren was confirmed, provided Richard de Goldeburg did not hunt in the lands of the king’s forest i.e. the ‘Park of the Hay’ to the north (English 1996, 213-4).

Whether there was an enclosed park at this stage is not clear and later documents relating to the estate do not mention one. On 10 August 1352, Sir Richard de Goldesburgh held the manor of Goldesburgh and attached to it was a capital messuage with 2 dovecotes and 2 orchards, 210a of arable land, 25a meadow and several pastures and underwood (Goldsbrough 1930, 67). The site of this manor house is thought to be due west of the current hall at SE 379 559, where there are remains of a moat. The first evidence of a park is the map by Christopher Saxton made in 1577 (British Library EBORACENSIS Comitatus f.61) that shows it covering most of the area to the south of the church. It is also depicted on John Speed’s map of 1611 (Figure 1).

Following the death of Thomas Goldesburge (Goldsborough) in 1566, the estate was left to his granddaughter, Anne, as his eldest son (her father) had died three years earlier. However, Thomas’s second son, Richard, disputed her claim and matters came to a head in 1582 when Anne and her husband, Edmond Kighley, issued a bill of complaint against Richard. In this Richard claimed he had ‘an estate of inheritance in the Manor of Goldesbroughe and also in Goldesbroughe Park, which was well stocked with deer and all manner of game, being an ancient Park of warren’ (TNA SP 46/184/134 & 135; Paley 1893, 221-2). This was his reason for allowing armed men to enter the park and to hunt with dogs. When the park keeper tried to stop them, they surrounded the park lodge and attacked its keeper (ibid).

A separate dispute about the manor house started two years later when the Kighleys’ tenant was evicted by Richard Goldsborough. In 1586, it was judged that the Kighleys did own the hall but that Richard and his men had:

‘pull[ed] down to the ground the Capital Messuage called Gouldisbroughe Hall and all the barns, stables, dovecotes, brewhouses and kilns & one new building called Aldborough parlour & all the edifices & buildings thereto belonging…The capital messuage is utterly destroyed and nothing remaining but only the soil or ground where the house did stand, being a house of ancient time and countenance, worth £1000 at least…[in] Goldsborough park…with force and arms [Richard et al] did pull down a great quantity of the pale of the said park…and did drive out…three score [60] of the deer…whereby there is no deer left’ (Paley 1894, 37)

In the survey conducted in 1758 (WYL250/3/Sur/11), there is a reference to an area called ‘Lodge Hill’, which was located between Great Wood and Pikeshaw Wood and is possibly the building shown within the park on Warburton’s map of c. 1720 (Figure 2). This map also shows its southeast boundary being Gundrif’s Beck. From this, the likely boundaries and extent of the park are marked in Figure 3 and covered about 300 acres, including c. 79 acres of open ground that is listed in the 1758 survey (ibid).

Whilst it appears that the park remained intact, when Sir Richard Hutton bought the property c. 1599, the manor house was destroyed. He decided to build his house in a new location adjacent to the church, which was completed c. 1610. There is no documentary evidence relating to the grounds around the new hall and the earliest plan is thought to be a proposal (WYL160/M285 [Plan 4], Figure 4). Probably dating from after 1692 when Robert Byerley senior married Mary Wharton, the only element that was certainly constructed was the four-square walled kitchen garden. Other features such as the bowling green, parterre, circular arrangement of trees and the three formal pools do not appear on any subsequent plans or maps.

The steps from the east front of the hall may have been implemented as they are shown on another undated plan (ibid [Plan 1], Figure 5). This postdates Plan 4 as it shows the new service buildings next to the churchyard. It also depicts an oval shaped parterre with paths cut into being planned (or implemented?) to the west. Little other detail of the grounds is apparent apart from the square garden next to the south front of the hall with the latter’s remodelled exterior.

The third plan (ibid [Plan 3], Figure 6) details all the service buildings and shows the extant kitchen garden with the area to the east that is possibly a canal or pool. This is probably from the late 1720s after Robert Byerley junior had come of age and inherited the estate in 1723. He had been on a Grand Tour between September 1720 and May 1722 when he had visited Germany, Belgium and France, including a visit to Versailles (Wilson 1876, 152) that may have inspired him. He and his companion, William Hutchinson, intended to visit Italy and had reached Marseilles before being ‘recalled to England’ (ibid, 153). However they set off again in July 1723 and this time reached as far as Genoa the following summer but again were back in England by July 1725 (ibid, 155 & 157). By 1729, Robert had died and his younger brother, Philip, inherited the estate although he too was dead by 1735, leaving Goldsborough to his two surviving sisters.

The final plan (ibid [Plan 2], Figure 7) is probably from the mid-1730s, just before the 1738 estate map (WYL250/3/Map 25, Figure 8). There are payments to the gardener, John Thomas, for baskets and spades bought between June and September 1735, with further payments to 2 labourers, John Robinson and Richard Greaves, for 22 days’ work in the ‘gardens’ in September and October of that year (NYCRO ZDS XVII/3). While the plan is sparse on detail, it shows the walled kitchen garden having a separate top third and paths to the south of it, both of which are shown in the estate map (WYL250/3/Map 25). The latter shows in detail the redesign with the distinctive bastions, which are similar in style to those in Stephen Switzer’s design for Grimsthorpe Castle that was made in 1716 (Jacques 1990, 19) and a new parterre garden.

There is a family connection as Mary Byerley’s father and Robert Bertie’s mother (the owner of Grimsthorpe) were first cousins and so the Byerleys may visited have Grimsthorpe or indeed come into contact with Switzer directly. Other features shown on 1738 map point to more influences from the work of Switzer including the former park divided into fields to create a ferme ornée with possible raised walks along the field boundaries (William Brogden, pers. comm.). Some of these wider than usual field boundaries are still extant in the landscape but currently have depressed rather than raised areas in the middle. The pool or canal to the east of the kitchen garden is similar to the one that Switzer shows in his book The practical kitchen gardiner (1727, 1; Figure 9).

Looking at the former boundaries shown on the Woods plan, the courtyard to the east of the hall (with its associated structures) may have been cleared by 1758, together with the formal garden to the southwest. In the latter’s place a path leading to the southwest bastion may have been put in, as there are payments to the labourer, Richard Greaves, for 11 days work in the gardens in March 1741 and 11½ days in October 1742. In addition, Richard Hodges was paid for carting gravel at the same time (NYCRO ZDS XVII/3). There is a reference to a payment to Chris Sanderson on 11 April 1772 to ‘stubing [removing trees] in the Grove’ (WYL250/3/ACS/287), so perhaps there were groves or wildernesses either side of this path. All these changes would have been instigated by Anne and Elizabeth Byerley, who inherited the estate in 1735.

By 1758, Elizabeth Byerley had decided to sell Goldsborough as the sole surviving sibling. Daniel Lascelles had acquired the neighbouring Plumpton estate in 1756, to fulfil a condition of his father’s will to use part of the inheritance to buy property (Lynch 2009, 123-4). He first started discussing the purchase of Goldsborough with his steward, Samuel Popplewell, in early 1759 (WYL250/SC/2/3/44, 49 & 56), however it appeared that the parties could not agree on the price. They finally settled in late 1762 when Popplewell noted on the 27 December in a letter to Lascelles:

I am not sorry that you have purchased Goldsbrough. It is a desirable acquisition & it is certainly prudent for gentleman of your rank to increase their property as near as possible to their mansion house, tho’ at an extravagant price. Had you once it let it slip perhaps it might not have been easily come at hereafter. (WYL250/SC/5/49)

Chronological history of the designed landscape

1763 – 1794

Having finally completed his purchase, Lascelles now turned his attention to improving the hall and the grounds. At the same time, he abandoned his plans for a new house at Plumpton, although he continued with the pleasure grounds there (Lynch 2009, 127). His first choice of designer was Richard Woods, who would work for his brother, Edwin, at Harewood and cousin, Edward, at Stapleton Park the following year (Cowell 2009, 202-3). Woods’ first commission in Yorkshire had been at Cannon Hall in 1760, with nearby Cusworth Hall a year later (ibid, 25) and these may have influenced Lascelles’ decision.

Sometime before October 1763, Woods submitted his plan (Figure 10) with its focus on the existing garden areas immediately south of the hall. Although Woods had been landscaping the parkland at both Cannon and Cusworth, the only change here to the wider landscape was a piece of water to the east of the walled kitchen garden. It is not clear whether this limited plan was Woods’ idea or imposed on him by Lascelles who was either concerned about the cost or happy with the existing layout. Sometime between delivering the plan and starting work, Lascelles decided the old kitchen garden needed to be moved to a new site east of the church. On the 13 October, Richard Swailes was paid for ‘Garden Walls £39 3s 2d’ (WYL250/3/ACS/287), which was likely to be for removing the old garden. With this large part of the area altered, Woods sent his foreman, Edward Richardson, to start work by 10 November (ibid).

The regular payments to Richardson for labourers continued into 1764 although it is not clear exactly what they are doing despite Popplewell making regular trips there to report on progress to Lascelles (WYL250/SC/5). On the 11 June 1764, Woods wrote to William Stones (WYL100/C/23A):

You are to go down to Goldsborough near Knaresborough in Yorkshire the seat of Daniel Lascelles. You are to relieve Mr Edward Richardson who is there & to take your instructions from him for carrying on the ground works there…I shall be down with you early in July & in the meanwhile I wish good health and success.

This suggested they were mainly clearing the area of the old formal gardens and perhaps preparing for the new kitchen garden site.

By the 30 June, Stones had taken over as foreman. In the archives is an undated memorandum from Woods with a copy by Stones (WYL100/EA/19/1, Appendix) detailing work that needed to be done. The five ‘articles’ were as follows:

- To get the haha sunk ready for the wall next to the new kitchen garden

- To get all the ground of the pleasure garden formed & turfed and then begin planting

- Form the ground at the front of the House & to make it correspond with the garden lawn

- Make the new kitchen garden

- Make the piece of water

Clearly progress was slower than Lascelles expected as Woods wrote to Stones on the 29 December:

‘I have this morning been with Mr Lascelles who wants to know of me how forward his Business is advance at Goldsborough, supposing that you often wrote to inform me…I find Mr Lascelles is not so well satisfied as you seem to imagine’ (WYL100/EA/19/1).

There is little information as to which elements of Woods’ plan were being carried out, apart from a letter from Popplewell to Daniel Lascelles on 9 Feb 1765 saying ‘Stones with his men at present are levelling the hill before the south corner of the house’ (WYL250/SC/5). Even this is ambiguous as it could refer to the site of old kitchen garden or the southwest bastion, which Woods had indicated to be removed in his plan. There was however a bill for 316,500 bricks on the 21 September (WYL250/3/ACS/287) suggesting that work was underway on the kitchen garden. On the 4 November, John Telford was paid £30 7s 6d for sundry shrubs (ibid) that was possibly for area around the south of the church.

Both the plantation and the new kitchen garden are shown on White’s plan of the following year as existing features, thus confirming that they were part of Woods’ design. The unusual extant hothouse built into the northeast corner of the kitchen garden wall is similar to other designs by Woods such as the one at Wardour (Fiona Cowell, pers. comm.) and White is not known to have designed any buildings.

There is an undated draft letter from Stones probably to Woods (WYL100/EA/19/1) that said White

‘hath been at Gouldsbro 3 times but hath done no business and he is to draw a plan but nothing to be altered that is finished’ and ‘since he [Lascelles] came down from London there is no placating on any count not only me but all about the place’

suggesting Lascelles was unhappy with what was going on and intended to replace Woods. White had become an independent designer in late 1765 with commissions for Busby Hall and Harewood (Turnbull and Wickham 2022, 22-5). White’s plan (Figure 11) showed that Woods’ scheme for the pleasure grounds in the old garden area and the new piece of water had been abandoned. Was this because White advised against it or again Lascelles wanted something cheaper and simpler? The only addition that White had made was to include a pleasure ground to the west of the hall.

When White took over is not clear however the amount being paid to labourers increased significantly between 29 March and 5 July 1766. On the 12 July, John Telford was paid £28 15s 6d for sundry shrubs (WYL250/3/ACS/287), which was perhaps for the new western pleasure ground. By the beginning of 1767, Stones had left to go and work for White at Newby Hall (Turnbull and Wickham 2022, 26). John Yateman then took over responsibility for ‘sundry labourers’ (WYL250/3/ACS/287), although whether he was appointed by White to complete the work or employed directly by the Goldsborough estate is unknown. However regular payments to him for the labourers continued until October 1772 (ibid): £174 in 1767, £215 in 1768, £201 in 1769, £198 in 1770, £143 in 1771 and £120 in 1772.

There were also further payments to John Telford for ‘sundry shrubs’ of £11 9s on 30 December 1767 and £21 17s on 22 October 1768 indicating further planting in the pleasure grounds (ibid). Telford was also paid for ‘sundry trees and shrubs’ totalling £10 17s 6d on 25 November 1769, £8 3s 7d on 4 September 1770, £4 7s 6d on 31 Dec 1771, £1 11s 6d on 31 December 1772 and £12 17s 4d on 31 August 1773 (ibid). The purchase of the trees may indicate planting in the wider parkland.

More building was also going on with 241,860 bricks paid for on 3 October 1769, 270,200 bricks on 15 December 1770, 209,200 bricks on 13 December 1771 and 126,900 bricks on 18 December 1772 (ibid). These may have been for the hothouse built in the northeast garden wall and mentioned in 1781 when bark was bought for it (WYL250/3/ACS/262), the greenhouse north of kitchen garden shown on the c. 1797 map (WYL250/3/Map 27) and removed in 1824 (WYL250/3/ACS/495) or the icehouse referred to in 1782, whose location is unknown (WYL250/3/ACS/262).

By 1773, the new kitchen garden had been built that included the hothouse and possibly the greenhouse, together with melon frames. Whether the area previously occupied by formal gardens and the old kitchen garden had been largely cleared is unknown. The new pleasure grounds though to the south and west of church and to the west of the hall had been added, together with a sunk fence around kitchen garden and another to south of western pleasure grounds.

The account book for Goldsborough (WYL250/3/ACS/287) has no further entries from 1774. By this stage, Lascelles was spending most of his time in the south either in London or at Upper Gatton Park in Surrey that he was renting at the time of his death in 1784 (Lynch 2009, 128). His property, including Goldsborough, was due to be inherited by his brother and Edwin may have been planning to rent it out, as work appears to have started again on the grounds in 1781 (WYL250/3/ACS/262). The tenant from c. 1786 was probably Margaret, Lady Cunningham of Robertland (1721 – 1811). There is a letter from a Lady Cunningham to Edward Lascelles regarding relinquishing occupancy of the house at Goldsborough on 26 July 1795 (WYL250/SC/12/7) and she first appears in the land tax records as the occupier in 1786.

John Dickinson (1732 – 1827) was put in charge of the work done by the labourers from 1781 (WYL250/3/ACS/262) and would later be the head gardener there. He had been working at Harewood from at least early 1770 (Finch & Woudstra 2020, 83), possibly continuing to implement the plan by White including the walks in the pleasure ground (WYL250/SC/4/2/14). He was paid directly by Lancelot Brown in 1774 (£30) and in 1775 (£535) for the landscaping planned by the latter.

The works carried out under Dickinson’s direction at Goldsborough may have been a continuation of the White plan to clear the area occupied by the former gardens. It may also have been to update the existing design by further opening up the parkland. In the week commencing 29 Jan 1781, the labourers were recorded ‘in the garden planting the Lombardy Poplars in the Parsonage pasture…lead [carry by cart] the rubbish to fill up the sunk fence [and] thining oaks Brownhill’ (WYL250/3/ACS/262). Between 17 September and 10 November of that year, Richard Jaques was paid for making new fences on the lawn and behind the kitchen garden (ibid) and on the 3 December, the Telfords were paid £4 1s 1d for fruit trees & shrubs (ibid). On 18 February 1782, Benjamin Lawton was paid for rebuilding sunk fence wall (ibid).

In 1785, Edwin Lascelles put wood from Goldsborough worth £1,000 up for sale (WYL250/1/173), perhaps some of which was from Leases Wood as the area had been largely cleared on the later map. It may also have enabled the carriageways through the woodland to be constructed as John Allinson was paid for repairing the bridge in the wood at Goldsborough on the 31 December 1785 (WYL250/3/ACS/217).

1795 – 1847

On 25 January 1795, Edwin Lascelles died and all his estates, including Goldsborough, were inherited by his cousin, Edward. The latter’s daughter, Frances, had married the Hon. John Douglas and Edward requested in July that the current tenant, Lady Cunningham, move out so that Mr and Mrs Douglas could be accommodated there (WYL250/SC/12/7). This may have resulted in maintenance work being done such as repairing the hothouse and melon frames (WYL250/3/ACS/223) and replacing the thatch of the icehouse (WYL250/3/ACS/217). There were also minor changes to the layout with William Temple being paid on 30 January 1796 for ‘removing and dressing the pleasure ground fence at Goldsborough where the addition is made to it’ (WYL250/3/ACS/223) and on 2 April for ‘making trellises for the garden wall and assisting to draw the trees from the wall in the garden’ (ibid). On 7 January 1797, Stephen Midgley was paid for ‘stubbing [removing] trees in the low orchard and drying yard’ (ibid) that was to the north of the pleasure grounds.

By 1797, Mr and Mrs Douglas had moved in and a survey was taken at this time (WYL250/3/Sur/12). The entry for Goldsborough Hall included ‘Kitchen Garden walled in – Hothouses – Shrubbery – Plantations’ with ‘The Site of the House etc’ listed as 9a 29p, which was the same as the 1758 survey (WYL250/3/Sur/11) showing that the site of the former gardens was still a distinct area, even if it now largely a lawn. There were two further areas covering in total 1a 3r 31p that was the western pleasure ground and the kitchen garden complex now covered 2a 2r. The map dated to c. 1797 (WYL250/3/Map 27, Figure 12) shows the revised layout including a new pond east of Leases Wood with a plantation to the north. There is no reference to it in the accounts, so when it was added is unclear.

Apart from John Wilson being paid on the 28 Jul 1798 for ‘making a hedge between the lawn below the house at Goldsborough and the Lease Wood’ (WYL250/3/ACS/223), there is little activity recorded in the account books for Goldsborough up until 1820. John and Frances Douglas had moved out in 1802 and the land tax records shows the tenant was James Starkie (or Starkey) from then until 1822. Edward Lascelles died in 1820 and was succeeded as 2nd Earl by his son Henry. As Edward, Henry’s eldest son, was living abroad, his second son, Henry junior, and his family moved into Goldsborough in c.1823. As well as making repairs to the hall, Henry made alterations to the kitchen garden in 1824, including taking off the old coping, pulling down and rewalling garden walls, taking down old greenhouse and levelling base and the repair of sunk fence on and against the kitchen garden (WYL250/3/ACS/495).

Henry Lascelles and his family remained there until 1844, even after becoming the 3rd Earl and inheriting Harewood in 1841 (New Court Gazette, 18 December 1841). During his tenure, the parkland was opened up with the earlier map (WYL250/3/Map 27, Figure 12) showing the boundaries that were to be removed. According to a survey from c. 1843 (WYL250/Accn3292/46 [59]) and accompanying map (WYL250/3/Map 29), the park now covered just under 87 acres (1st edition OS map, Figure 13). Four years later, this had expanded to the east up to the ‘New Cut’ drain and measured 120a on the tithe map and apportionment (TNA IR 30/43/176, Figure 14).

1848 – 1892

The next occupant from 1848 was Henry, Viscount Lascelles, until he succeeded his father as the 4th Earl in 1857. There are significant purchases of ‘Forest Trees’, rhododendrons, yews and laurels in October 1849 and December 1850 from a variety of nurseries including George Cunningham of Oak Vale nursery, West Derby, Liverpool (WYL250/3/ACS/218) for the pleasure grounds but possibly for the large wooded area to the south. The latter may have been in the process of being replanted as Mr Warne was paid £102 on 1 January 1853 for nursery trees (ibid). In the kitchen garden, two additional glasshouses had been added by 1863, as well as a terrace on the south side of the hall (WYL250/3/Map 31). More land was added to the to the southern section of the park next to the woods that had previously been arable land.

Between 1867 and 1881, it was rented by tenants outside the family and then occupied by Henry, Viscount Lascelles (later 5th Earl) until 1892. The tenant from mid-1871 was Sir Andrew Fairbairn and he may have been responsible for commissioning a redesign of the ‘flower garden’, with the plan (private collection) dated May 14 1871. It is signed ‘H. E.? B.’ and it may be the work of an architect, Henry Edwin Bown (1845 – 81), who was based in nearby Harrogate. Its 3D style is similar to other architects who also later designed landscapes such as Reginald Blomfield. The proposed garden building and the two parterre gardens do not appear on later maps, so it is likely that they were not implemented. Photographs taken in 1895 (Harewood House Trust) show many mature shrubs and trees surrounding the south and east façades of the hall. In 1892, the hall was once again rented out, this time to William R Lamb, who stayed until 1921.

1922 – to date

Henry, Viscount Lascelles (later 6th Earl) married Princess Mary on 28 February 1922 and Goldsborough became their home in December of that year. As well as making alterations to the hall, they made the first significant changes to the grounds in nearly a century. Princess Mary was a keen gardener and she may have had advice from the designers William Wood & Son who had advised on other royal gardens and had been paid £5 5s 9d on the 23 February 1923 (WYL250/Accn3292/28 [23/2]).

To the south of the hall new twin herbaceous borders, nearly 120ft long and backed by beech edging, were put in during 1923 (ibid, Figure 15). To the south of this was added the Lime Tree Walk. In the western section of the walled kitchen garden a rose garden was added, which was the subject of a painting by Beatrice Parsons in 1930 (Harewood House Trust). On 17 December 1926, W Cutbush & Son Ltd were paid £1 13s 9d for roses (WYL250/Accn3292/28 [23/3]).

On 24 January 1924, Princess Mary wrote to Sir Charles Cust about the plans for cutting down old and planting new plantations (LA BNLW/4/4/10/174). This may refer to the planting to the west of the pleasure grounds next to the site of the old manor house that had previously been an open field. On his father’s death in late 1929, Lord and Lady Lascelles moved into Harewood the following year and Goldsborough was once again rented out. In 1952, the estate was put up for sale and the hall and immediate grounds were bought by the Boyer family who ran it as a school. It then operated as a care home prior to the current owners acquiring it. The land inside the old walled kitchen garden was sold off and houses were built inside the walls, although large parts of the walls remain.

Location

Goldsborough is 2 miles (3.5km) southeast of Knaresborough and 5 miles (8km) east of Harrogate.

Area

The historic designed landscape of Goldsborough at its greatest extent was c. 325 acres (132 ha).

Boundaries

The northern boundary is formed by the road from SE 392 561 in the east to SE 382 561 in the west. The boundary to the west starts here and then follows the northern extent of the pleasure grounds to SE 380 560. It then goes south along the western edge of the park and Great Wood to SE 386 546. The southern boundary is formed by Gundrif’s Beck until SE 393 554, where the eastern boundary goes north along eastern edge of Pikeshaw Wood and then follows the Great Dike to SE 392 561.

Landform

Around the hall and the pleasure grounds, the underlying bedrock is Brotherton Formation of limestone. The majority of the park’s bedrock is Roxby Formation – Mudstone, however the woodland and rest of the park is Sherwood Sandstone Group. This is overlaid with superficial deposits of clay and silt. The soil throughout is base-rich loam and clay but they are slowly permeable, seasonally wet and slightly acid with impeded drainage giving moderate fertility.

Setting

Goldsborough lies in the National Characterisation Area 30 (Southern Magnesian Limestone). This is a ridge of elevated land running north-south with light, fertile soils. It is mainly open, rolling arable farmland enclosed by hedgerows, plantation woodlands and estate parkland. The watercourses that run through it, such as the one next to Goldsborough, provide areas of wetland. The limestone has provided much building material for the many large houses in the area.

Goldsborough Hall stands on an elevated position at 43m AOD, with the ground sloping down south to the northern edge of the former Leases Wood at 30m AOD. It then rises again in the Great Wood to 55m AOD before falling to 31m AOD at Gindrif’s Beck. From west to east, the ground gradually falls away from c. 40m OD to c. 29m OD.

Entrances and approaches

Gatepiers at village entrance [Grade II – NHLE 1149951]

Located at SE 37996 56264, the gatepiers mark the entrance to the village on the road from Knaresborough. Preceding them is an avenue of trees that is shown on the c. 1797 map and the gatepiers have been dated to the late 18th century.

Entrance to park off Mill Road

Added in the early 19th century, this entrance at SE 380 560 led to a carriageway that went east just south of the pleasure grounds towards the hall.

Entrance off Cinder Walk

Off the main street of the village, this was the original entrance to the stableblock and hall.

Principal buildings

Goldsborough Hall [Grade II* - NHLE 1315586]

Built c. 1610 for Sir Richard Hutton with alterations c. 1743 for Elizabeth and Ann Byerley, in 1762-5 for Daniel Lascelles by John Carr and in the 1920s by Sidney Kitson for Lord Lascelles and Princess Mary. There have been further changes in the late 20th century when it became a school, then a nursing home and now is a country house with accommodation and restaurant.

Stables & coachhouse [Grade II - NHLE 1149950]

Extant by the early 18th century, it may have been altered by John Carr for Daniel Lascelles in the 1760s. It has now been converted into residential accommodation.

Church of St Mary [Grade I – NHLE 1149951]

Built in the 13th century with restorations in 1750 and in 1859.

Hothouse

Built into the rounded northeast corner of the walled kitchen garden, this was probably designed by Richard Woods c. 1764 and built before 1773. It had a glazed roof and at the back is a fireplace in order to heat it.

Gardens and pleasure grounds

Gardens prior to 1763

When Goldsborough Hall was built in the 1620s, there may have been gardens laid out next to them following the fashion of the time, however there is no evidence of them. When the Byerleys came to live at the hall in 1692, they may well have wanted to update the grounds and there are four plans indicating possible improvements to be made (WYL160/M285, Figures 4 to 7). To the west a bowling green and then an oval parterre (Plans 4 and 1 respectively) were proposed but no evidence that either was built on this sloping piece of ground. Next to the south front of the hall were a series of gardens including a parterre (Plan 4) and a walled section labelled ‘Garden’ (Plan 3) that may have been a kitchen garden area. Beyond this, there is a proposal for a circular group of trees possibly with a mount at the centre (Plan 4).

The land adjacent to the east front falls away sharply and the plans for this area offer different solutions. Plan 4 is the most ambitious with two sets of steps and a circular terrace walk around what may be a lawn in the centre. This then leads to a series of three geometric ponds. While the later Plan 1 does show two sets of steps next to the hall, the terrace walk is absent. The plans from the 1720s and 1730s (3 and 2 respectively) show a defined courtyard with steps immediately next to the hall, twin square beds in the centre and two square built structures (gateposts?). Further east is an open area that leads to a path east of the kitchen garden and out into the wider landscape.

Elizabeth and Anne Byerley then developed a c. 6a area to the south that is depicted in the 1738 map (Figure 8). The distinctive layout with its twin bastions may well have been inspired by or indeed designed by Stephen Switzer (see Section 3.2). In the middle of these are marked by a single tree both in the earlier map and Woods’ plan (Figure 10), which may have been the walnut trees that were taken down in early 1813 (WYL250/3/Acs/223). Between these and the kitchen garden to the north may have been a wilderness or grove as some mature trees are shown there on Woods’ plan.

To the west of the kitchen garden is another defined garden area with an elaborate layout that is reminiscent of both Switzer’s ideas and Batty Langley’s designs published in his book New Principles of Gardening in 1728 such as those in Figure 16 (Plate VIII). Little appeared to have remained by the time Woods made his plan, perhaps due to the expense of maintaining it. To the north of this is an open area that is shown as a lawn on Woods’ plan and labelled ‘Garden’ on Plan 3.

Pleasure grounds

The first pleasure grounds to the east were put in according to Woods’ plan and provided a screen for the new kitchen garden east of the church. To the west of the hall and covering c. 4.5a, White planned further pleasure grounds that were in place probably by 1773. These two areas were combined when the boundaries of the former gardens were removed c. 1797 and amounted to c. 8.5 acres.

20th century gardens

In late 1922, the area due south of the hall was cleared to create the twin herbaceous borders the following year (WYL250 3929/28 [23/2]). In the lawn in between them was put a sundial given to Princess Mary by The Hornton Village Stone Industry of Banbury in Oxfordshire. Adjacent to the hall a new terrace was built with a wide paved area and lawns either side of the steps down with two clipped yews. The beds in front of hall were filled with more herbaceous planting to mirror that of the long borders. The accounts for 1926 record the many purchases of plants for the garden including carnations from C Engelmann of Saffron Walden and dahlias from Carter Page & Co of London (WYL250 3929/28 [23/3]).

Kitchen garden

The first known kitchen garden was south of the hall and covered c. 1⅓ acres. It was likely to have been added by the Byerleys after 1692, possibly replacing the one due south of the hall noted as ‘Garden’ on Plan 3 (Figure 6). Originally divided into four sections, by the 1730s there were six areas, with the northwest section laid out more formally with a central circular area (Figure 8). By the eastern wall was a canal, similar to the idea proposed by Switzer (see Section 3.2). Although Woods had proposed keeping this garden, a decision was made to make a new garden to the east of the church in 1764. This was part of the former ‘Saunders Orchard’, which implies it had previously been a productive area.

The new structure is shown on White’s plan of 1766 (Figure 11) with rounded corners on the northern wall. Woods had used this style in other commissions such as the one for Carlton Towers (1765) and possibly for Stapleton Park (c. 1763-4). The walled area covered just under 2 acres and a further ½ acre to the north, next to the public road, was added for additional buildings such as the freestanding greenhouse. A hothouse was built into the wall at the northeast corner (see Section 4.7.4) and there were melon frames but their exact location is unknown.

In 1824, the walls were rebuilt and the old greenhouse to the north was removed, with a new structure put in its place. By 1863, two further glasshouses had been built in the interior and there was a small glazed structure in the northeast corner (Figure 17). In the 1920s, the western section of the walled garden was made into a rose garden.

Park and plantations

Former deer park

Although the first reference to this is in the 1570s, it had clearly been in existence sometime before this, as the Goldsborough family had had a grant of free warren since the mid-13th century. However, it is more likely to date from the 15th century.

Park

Originally an open area of ground of 79 acres in the former deer park, by 1738 it had been divided into fields. These boundaries were removed in the early 19th century and from 1843, it began to be enlarged to cover 120 acres. By 1863, the area to the south next to the woodland was added, thus increasing the size to 168 acres and by the end of the 19th century, it had reached its full extent of 209 acres.

Leases Wood

First shown on the 1738 map and measuring 12 acres, this distinct area of woodland has been steadily reduced over time and no is longer extant.

Great Wood

Possibly part of the woodland noted in the Domesday book, this probably was formed as the southern part of the medieval deer park. Covering 84 acres, it is still extant.

Pikeshaw Wood

Possibly part of the woodland noted in the Domesday book, this probably was formed as the southeastern part of the medieval deer park. Covering nearly 16 acres, it is still extant.

Water

The 1 acre Leys Pond was first shown on the c. 1797 map and may possibly have been added to provide ice for the icehouse.

Books and articles

Cowell, F. 2009. Richard Woods: Master of the Pleasure Garden. Woodbridge, Boydell Press.

English, B. ed. 1996. Yorkshire Hundred and Quo Warranto Rolls 1274 – 1294. Yorkshire Archaeological Society.

Farrer, W. ed. 1914. Early Yorkshire Charters Vol. I. Yorkshire Archaeological Society.

Finch, J. and Woudstra, J. (Eds.), Capability Brown, Royal Gardener: The business of place-making in Northern Europe, 33–47. York, White Rose University Press.

Goldsbrough, A. 1930. Memorials of the Goldesborough family. Cheltenham, E.J. Burrow.

Jacques, D. 1990. Georgian Gardens: The Reign of Nature. London, B. T. Batsford.

Lynch, K. 2009. ‘Extraordinary convulsions of nature’: The Romantic Landscape of Plumpton Rocks. In Kellerman, S. and Lynch, K. eds. With abundance and variety, 123-42. York, Yorkshire Gardens Trust.

Paley Baildon, W. 1893. A Chapter in the history of Goldsborough. Yorkshire County Magazine Vol. III, 217 – 225.

Paley Baildon, W. 1894. A Chapter in the history of Goldsborough Part II. Yorkshire County Magazine Vol. IV, 33 – 45.

PRO 1906. Calendar of the Charter Rolls, Vol II, Henry III-Edward I, 1257-1300. London, HMSO.

Turnbull, D and Wickham, L. 2022. Thomas White: redesigning the northern British Landscape. Oxford, Windgather Press.

Wilson, H. S. 1876. The Grand Tour a Hundred and Fifty Years Ago. The Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol. 241, 147-59.

Primary sources

Harewood House Trust (HHT)

Photograph album of Goldsborough, 1895

Paintings by Beatrice Parsons of Goldsborough gardens, 1930

Lincolnshire Archives (LA)

BNLW/4/4/10/174 Letter from Princess Mary to Sir Charles Cust, 24 January 1924

North Yorkshire County Record Office (NYCRO)

ZDS XVII/3 William Hutchinson as agent for the Byerley family: papers 1723-50

Private collection

Plan for a proposed alteration of flower garden at Goldsborough Hall, 14 May 1871 by ‘H. E? B.’. Copy at Goldsborough Hall.

The National Archives (TNA)

IR 29/43/176 Tithe apportionment for Goldsborough, 21 December 1846

IR 30/43/176 Tithe map for Goldsborough, 1847

SP 46/184/134 & 135 Bill of complaint of Richard Goldsborough against various parties, c. 1592-93

West Yorkshire Archives Services Leeds (WYASL)

WYL100/C/23A Letter from Richard Woods to William Stones, 11 June 1764; diagrams from memorandum from Woods to Stones (nd)

WYL100/EA/19/1 Letters from Richard Woods to William Stones, 11 October 1764 and 25 December 1764; memorandum from Woods to Stones, original and Stones’ copy (nd); draft letter from Stones to Woods? Nd

WYL160/M285 4 plans for possible improvement to grounds at Goldsborough, nd (c. 1692 – 1738)

WYL250/1/173 Agreement to sell wood, 20 May 1785

WYL250/4/12/1 A Design for the Improvement of Goldsborough the Seat of Daniel Lascelles, Esqr. By R. Woods 1763

WYL250/4/12/2 Thomas White, A Plan of Alterations designed for Goldsborough, 1766

WYL250/3/ACS/217 Goldsborough, Plompton and Bramham accounts, 1783-1817

WYL250/3/ACS/218 Cash book of William Somerville, relating to Goldsbrough Estate and woods, 1848-58

WYL250/3/ACS/223 Labourers at Plompton and Goldsborough wage book, 1785-1820 by William Popplewell

WYL250/3/ACS/262 Labourers at Goldsborough wage book, 1781-4 paid by John Dickinson

WYL250/3/ACS/287 Ledger (Mr Watson), 1763-1773 regarding building, gardens etc at Goldsborough

WYL250/3/ACS/495 Account books incl work at Goldsborough Hall, 1813-24

WYL250/3/Map 25 A New and Correct Plan of the Manor of Goldsborough the seat of Madam Ann and Elizabeth Byerleys. By Thomas Pattison, 1738

WYL250/3/Map 27 Map of Goldsborough, c. 1797

WYL250/3/Map 29 Map of Goldsborough, c. 1843

WYL250/3/Map 31 Map of Goldsborough, 1863

WYL250/3/Sur/11 Survey of Goldsborough, 1758

WYL250/3/Sur/12 Survey of Goldsborough, c. 1796

WYL250/SC/2/3/44 Letter from Daniel Lascelles to Popplewell, 22 February 1759

WYL250/SC/2/3/49 Letter from Daniel Lascelles to Popplewell, 26 February 1759

WYL250/SC/2/3/56 Letter from Daniel Lascelles to Popplewell, 6 March 1759

WYL250/SC/4/2/14 Letter from Edwin Lascelles to Popplewell, 3 March 1773

WYL250/SC/5 Steward’s letter book 1763-92

WYL250/SC/12/7 Letter from Lady Cunningham to Edward Lascelles, 26 July 1795

WYL250/Accn3292/28 [23/2] Viscount Lascelles account book 1922-3

WYL250/Accn3292/28 [23/3] Viscount Lascelles account book 1926

WYL250/Accn3292/46 [59] Survey of Goldsborough, c. 1843

Maps

1st edition 6” Ordnance Survey map, surveyed 1846-51, published 1853

Revised edition 25” Ordnance Survey map, revised 1907, published 1909

Figure 1 – Goldsborough deer park shown on John Speed’s map of c. 1611. Cambridge Digital Library CC-BY-NC 3.0

Figure 2 - Goldsborough park with lodge from John Warburton’s map of Yorkshire c. 1720. The Virtual Library of Bibliographic Heritage, Spain CC BY.

Figure 3 – likely extent of medieval deer park on revised 6” OS map, published 1910. National Library of Scotland CC-BY.

Figure 4 – Plan of Goldsborough Hall and gardens, n.d. [Plan 4] (WYL160/M285). Used with permission from West Yorkshire Archives Service, Leeds.

Figure 5 – Plan of Goldsborough Hall and gardens, n.d. with annotations [Plan 1] (WYL160/M285). Used with permission from West Yorkshire Archives Service, Leeds.

Figure 6 – Plan of Goldsborough Hall and gardens, n.d. with annotations [Plan 3] (WYL160/M285). Used with permission from West Yorkshire Archives Service, Leeds.

Figure 7 – Plan of Goldsborough Hall and gardens, n.d. [Plan 2] (WYL160/M285). Used with permission from West Yorkshire Archives Service, Leeds.

Figure 8 - detail of estate map from 1738 showing gardens and bastions (WYL250/3/Map 25). West Yorkshire Archives Service, Leeds. Published with kind permission of the Harewood House Trust.

Figure 9 - Plan of a kitchen garden with a canal at the bottom by Stephen Switzer. From The practical kitchen gardiner, 1727 - https://archive.org/details/practicalkitchen00swit/page/n57/mode/1up

Figure 10 – Plan by Richard Woods of improvements to Goldsborough, 1763 (WYL250/4/12/1). West Yorkshire Archives Service, Leeds. Published with kind permission of the Harewood House Trust.

Figure 11 – Plan by Thomas White for improvements to Goldsborough, 1766 (WYL250/4/12/2). West Yorkshire Archives Service, Leeds. Published with kind permission of the Harewood House Trust.

Figure 12 – Detail from estate map of Goldsborough c. 1797 (WYL250/3/Map 27). West Yorkshire Archives Service, Leeds. Published with kind permission of the Harewood House Trust.

Figure 13 – Goldsborough estate on 1st edition OS map, surveyed 1846-51, published 1853. National Library of Scotland CC-BY.

Figure 14 – Extent of parkland at Goldsborough on tithe map of 1847 (IR 30/43/176). ©The National Archives.

Figure 15 – Goldsborough Hall and gardens, 1928.

Figure 16 – Design by Batty Langley from New principles of gardening, 1728. https://archive.org/details/mobot31753000819141/page/n240/mode/1up

Figure 17 – Walled kitchen garden showing glasshouses (hatched areas) from revised 25” OS map, published 1909. National Library of Scotland CC-BY.

Memorandums for William Stones to carry on the improvements at Goldsborough (WYL100/EA/19/1)

First article is to get the haha sunk ready for the wall according to the section, only to observe to keep the slope of [that] wall a foot below the surface of the ground on the garden side so that the turfs may form an easy swell over it.

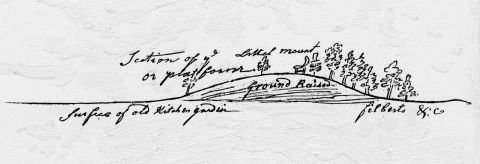

Second article is to get all the ground of the pleasure garden formed & turfed as soon as possible & the different borders quarters & clumps trench in readiness for planting. In forming the lawns you’ll observe to make soft swells where the stakes are placed marked No 1 but at the stake No 2 the ground is to be raised about a yard with a platform at the slope not less than 15 feet wide & to fall in a concave slope down to the level of the old kitchen garden & on each side to form swelling banks with their bases running farther out then the base of the concave so that the whole side of the wilderness towards the House may appear a waved bank. Let the earth fall back amongst the filberts in a kind of rough slope so as to support the platform.

Image used with permission from West Yorkshire Archives Service, Leeds (WYL100/EA/19/1).

The ground being all prepared begin the planting as soon as convenient & observe as follows: The winding lines of stakes are the boundaries of each border, quarter or clump. Let there be a margin left for flowers about 3 or 4 foot wide in which margin left for the flowers about 3 or 4 feet wide in which margin let those be a few roses jasmines & honeysuckle plants about 6 or 7 feet asunder to intermix with the flowers. The next begin with short shrubs & evergreens and so keep rising taller and taller still backwards. At the back of the seat upon the litter mount at the stake number 2 let it be principally be evergreens with some honeysuckles with them to climb up. All the white end stakes are for trees such as oaks, elms, beeches, chestnuts etc with some flowering trees mixed with them such as double blossomed peach ditto almond ditto cherry ditto thorn Glastonbury thorn pseudeosmia cherry arborjudae tulip tree etc & where the short single stakes stand up on the turf near the borders are to be chosen short growing plants such as Portuguese laurels, arbutus, striped hollies, ditto laurustinus ditto philerea, chenia, arborvitae, cistus several sorts etc sumach for planting only let all be watered at first planting & all tall plants staked.

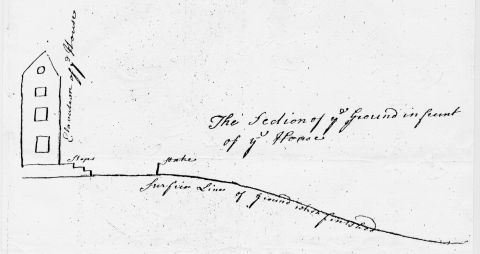

The third article is the forming the ground at the front of the House & to make it correspond with the garden lawn. First then you’ll observe the line of stakes is intended for the raise of the terrace, the ground must be formed in a hanging level form the House to that line & may fall in front of the hall about one foot. Then make the ground fall from that line downwards in a fine bold O:G: slope like the section on the other side & in order to do this you’ll want some earth to meet the hill where the wall is taken down, which earth must be taken out from the intended piece of water.

Image used with permission from West Yorkshire Archives Service, Leeds (WYL100/EA/19/1).

The fourth article is the new kitchen garden. In making of this garden, the ground must be so formed as that it may lie with such descents to prevent the water hanging as the bottom is a cold clay soil. The borders to be raised to the top of the plinth(?) & hang at least 6 or 8 inches in the ? a bason to be made 10 yards diameter at the stake placed for that purpose for the centre thereof & all the upper part of the ground laid with such descent as to cast the stale water down to the bason & all the ground be low & the bason to be so laid & drained as to carry the water into the haha at the east end & the best way to do it is to carry a stone drain down the middle or the lowest part & lead all the cross drains into it. If possible let the principal stone drain bounder the middle walk. In marks in the borders take care to dig out the clay where it lays shallow & lay in a bottom of bricks and mortar rubbish wall rammed down so as to prevent the roots shooting into the clay & when you plant the fruit trees, be sure to set them upon the slope of the border & so to raise hillocks round them, otherwise in a few years they will draw themselves down too deep, set them at least 9 or 10 inches from the wall.

The fifth article is the piece of water. In making of the water you’ll observe that the level of the surface is fixed at 2 foot 6 inches below the top of the centre level stake. The head is to be fixed at the stake No 3. A good rib of clay must be made along the lower side & across the head & must dig down a trench till you meet with a good clay bottom for its foundation. Let the slopes be made a very easy(?) at least 3 foot base to one foot fall.