The designed landscape of Kirby Hall was largely shaped by the decision of Stephen Thompson to build himself a new hall in 1746. He was a friend of Lord Burlington who is credited alongside Roger Morris, John Carr and Thompson himself with the design of the building. Taking advantage of a natural watercourse, Thompson created a serpentine ‘river’ possibly inspired by the one at Chiswick, the London home of Burlington. Stephen’s brother and nephew continued to develop the grounds from 1764, employing the designers, Adam Mickle II and possibly Thomas White, although the exact extent of their involvement is unknown as no improvement plans survive.

With a significant inheritance in 1814, Richard John Thompson had the funds to add to the designed landscape, commissioning a plan for the flower garden and a fountain from John B. Papworth in 1834. As the plan is now lost, it is unclear whether it was carried out. Thompson’s son, Henry, extended the hall and added other buildings including a second lodge and extensive glasshouses in the third quarter of the 19th century. By 1907, the parkland had reached its greatest extent however in 1919, the estate was sold and the 18th century part of the hall was demolished the following year. The designed landscape remained largely intact though and today provides an important setting for the remaining listed buildings of the Kirby Hall estate.

Estate owners

In 1086, Kirby Hall (or Kirby Ouseburn) was owned by the Norman, Osbern d’Arques [de Arches] and it devolved to his son, William, on his death in 1115. It remained with the de Arches family until the late 12th century when it became the possession of William de Stutevill. On the latter’s death in 1203, it passed to Fountains Abbey under a charter made by de Stutevill a few years prior to this. On the dissolution of the monasteries in 1540, it became the property of the king who leased the half of the manor of Kirby Hall to the tenants, William and John Dickinson in 1556.

By 1618, the Dickinson family had acquired the manor, together with ½ of the neighbouring manor of Thorp [Underwood] and land in Little and Great Ouseburn. It remained with the Dickinson family until the death of Thomas in 1671, who left 3 daughters as his heirs. The eldest, Ann, married Joshua Colston and they lived at Kirby until at least 1684. Between then and 1691, the property passed to Sir Stephen Thompson of York, with his son, Henry, inheriting on his death in 1692.

Henry Thompson died in 1760 and was succeeded first by his eldest son, Stephen, and then by his second son, John, in 1764. With the latter’s death in 1777, Kirby Hall remained with his direct male descendants until Henry Meysey Meysey-Thompson, who put the property is put up for sale in 1919 and it was bought by the family who owned it until late 2024.

Key owners responsible for major developments of the designed landscape and dates of their involvement:

Fountains Abbey 1203 - 1540

The Dickenson family 1556 – c. 1684

Stephen Thompson 1743 – 64

John Thompson 1764 – 77

Henry Thompson 1777 – 1814

Richard John Thompson 1814 – 53

Sir Harry Thompson [later Meysey-Thompson] 1853 – 74

Henry Meysey Meysey-Thompson [later 1st Baron Knaresborough] 1874 – 1929

Early history of the site

In 1086, Kirby [Hall] was owned by Osbern d’Arques and covered 2 ploughlands (c. 240 acres). It was possibly waste as it had no recorded population (https://opendomesday.org/place/SE4561/kirby-hall/, consulted 3 December 2024). Next to it was Thorpe Underwood that had 1 ploughland (c. 120 acres), 4 acres of meadow and woodland of 0.5 leagues x 4 furlongs (c. 480 acres). It was also described as waste and was the property of Ralph Paynel (https://opendomesday.org/place/SE4659/thorpe-underwood/, consulted 3 December 2024). Both manors were given to Fountains Abbey in the late 12th century by their respective owners, William de Stuteville (Kirby) and Geoffrey Haget (Thorpe Underwood). They remained as separate areas with the abbey leasing out the grounds of Kirby in 1507 to John Pulleyn for 40 years. This lease was taken over by William Dickenson senior, his wife Ann and son, William Dickenson junior, in 1522 (Michelmore 1981, 106). The lease referred to ‘their built-on capital messuage and half of the manor of Kyrkbyhall with all the appurtenances as he now occupies them’ (ibid), however there was no detail re the landholding.

When William Dickenson junior and his son, John, were granted the lease of half the manor from the Queen in 1556, it listed the following closes or fields: Netherfield, Parre (or Carr?) Garths, Fore Garth, The orchard, Berry Garth, Eliot Ings, Kirke (or Church) Close, Pillet Holme, Crossfield, Park Lane, Grimshaws field, William Croft, Broomfield and Boat Close (KULSC MT 196-199). In 1616, James I granted the manor of Kirby Hall to Sir Thomas Middleton and Richard Swale (KULSC MT 200-1), who sold it to William and Richard Dickenson the following year. In an inquisition in 1619 (KULSC MT 205), the Dickenson property was listed as having:

(a) capital messuage, kilnhouse, oxhouse and barns in Kirby hall, closes called Newhorse Close, William Croft, Low Crosfield, High Crosfield, Townend Close, Great Broomfield, North Broomfield, Pillot (Holme), Elliott Inge, Netherfield, Old Horse Close, New close, Ferry boat close and Broomfield Garth, in Kirby Hall, and North mill field, Corn booth Closes, Great boat Close, ---wlke(?) Closes, Thorpe Inge and Thorpe Close in Thorp Underwood.

The Kirby Hall estate remained with the Dickenson family though they appeared to have incurred debts, as the property was mortgaged prior to the death of Thomas Dickenson in 1671 (KULSC MT 280-94). Although it was inherited by his three daughters, by 1692 Sir Stephen Thompson of York had control of the estate. On his death, he passed it to his son, Henry, who moved there with his family in c. 1721, the date of the first baptism of his children recorded at Little Ouseburn church. In 1672, the main house was listed as having 15 hearths, which was a substantial property. The estate belonging to Henry Thompson, shown on the map of 1743, covered just over 637½ acres (NYCRO ZRR K [1743], Figure 1), although it was mostly fields. The other three landowners were Mr Horsefield [Horsfield], Mrs Browne and Mr Cass who held a further 124 acres in Kirby Hall (ibid).

By 1743, many of the larger fields had been sub-divided and enclosed apart from Berry Garths (marked ‘h’ on the map) immediately north of the hall. To the southeast were two areas of woodland: ‘Great Wood’ that covered just over 14 acres and ‘Little Wood’ of nearly 6 acres. In between these were two sections named ‘Outwood’ of nearly 9 acres that may recently have been cleared. The beck had been dammed at the western side of Great Wood to form a pond and at the eastern side to make a race for the adjacent watermill. North of the hall was an orchard and in front of it, there were gardens and possibly a formal canal. A walled area to the southeast adjacent to a service building, may also have been a garden (NYCRO ZRR K [1743], Figure 2). Marked next to the church was the newly erected mausoleum, for which Henry Thompson got a licence for burials within its vault in 1743 (KULSC MT 934).

Chronological history of the designed landscape

1744 – 1815

By 1744, Henry Thompson was 77 and had handed over control of the estate to his eldest son, Stephen, who wanted to improve the estate by building a new hall and redesigning the grounds. He first consulted the gentleman architect, Colonel James Moyser, in June 1746 (ERA DDGR/41/3/10) and received several plans from him. On 22 November that year, Thompson wrote:

‘I received from Col. Moyser a…plan that I like better than any I have seen yet. I sent him some remarks upon it and hope to have a second edition. If I take it right my house will be a perfect model of Lord Orford’s at Houghton…a House to live in not a House for Show’ (DDGR/41/3/17).

Moyser suggested that Thompson consult another architect, Roger Morris, perhaps because he disliked the latter’s interference. In a letter of 3 January 1747, Thompson commented:

I perceive that Mr Moyser does not approve my alterations of his plan but I can’t think these will be those difficulties he imagines as I am in great hopes. I am not far off the true plan that I shall execute which will be not unlike Sir C[harles] Hotham’s in Beverley excepting the additions. Morris has promised to call at Kirby in May in his way to Scotland…which time I shall let my plan keep (DDGR/41/5/2).

While he does not appear to have been successful in getting this land from his neighbour, the later map from 1766 (NYCRO ZRR K [1766], Figure 3), shows the beck had been widened to form a serpentine lake or ‘river’ on the land he did own. This was completed by March 1748 with his brother-in-law, Stephen Croft, commenting that ‘it’s worthwhile coming from London to see it’ (DDGR/41/5/9) and Thompson declaring it his ‘charming water’ in June (DDGR/41/5/19). The creation of the serpentine river may have been inspired by the one at Chiswick House in London (Figure 4) constructed in the early 1730s, which he must have visited as Thompson was friends with its owner, Lord Burlington.

By mid 1748, work was underway on the house largely to the design of Morris (Figure 5). In 1749, John Carr was appointed the new head of works (DDGR/41/6/19) with the building finally finished by September 1755 (DDGR/42/5/37). A new kitchen garden had been built on the other side of water and a small park of just over 57½ acres had been created to the east by opening up the fields by 1766. There was also a new carriageway from the north through Berrygarth along a former track, replacing the road that had previously been on the boundary of Berrygarth and Netherfield (Figure 3). When all these features were put in is not clear, however in June 1747, Thompson said that he was employing the lawyer, Yoward, about ‘turning his Roads’ (DDGR/41/5/5), perhaps a reference to the diversion of the public road that went south to the old hall.

He may have engaged someone to help him with the design. One possible candidate was Thomas Knowlton, who was not only the gardener to Lord Burlington at Londesborough but who also gave advice to other landowners on landscape design for their estates. These included South Dalton Hall, Everingham Park, Birdsall House and at Aldby Park where he was engaged between 1746 and 1749. Thompson’s friendship with Burlington and the latter being credited alongside Morris of the design of the house (Figure 5), meant that Thompson would have met Knowlton.

In two letters written on the 21 April and 10 May 1748, Thompson mentioned an overseer, ‘Pullein’ who had recently started working for Thomas Grimston but had clearly done some good work for Thompson previously. In the first letter, he advised Grimston:

‘[Pullein] has viewed your work & he was sure he could do it to your satisfaction if you would let him have his own way…he has been many years used to the removing of earth & therefore must be a better judge what this or that part will require…I am confident he will not advise you anything with a view to make work for himself & that if you tell him fully what you would have done you may rely upon both doing it well & going the neatest way about it as I have had great experience of his capabilities & integrity’ (DDGR/41/5/10).

At this point, he had engaged a new overseer and asked Grimston in the second letter to ‘let Pullein leave you on Sunday for 3 or 4 days to meet my new overseer & put him in a way of going on with my workmen as I shall begin to work in good earnest as soon as I get down which I hope I shall be soon’ (DDGR/41/5/16). Although the new overseer is not named, both men may have helped Thompson with the design but no other information has been found about them to explore this further.

Stephen Thompson died in 1764 and the estate was inherited by his brother, John. The estate in 1766 is shown on the estate map of that year (NYCRO ZRR K [1766], Figure 3). John may have had plans to landscape the grounds as there was a payment to the landscape designer, Thomas White, from a ‘Thompson’ on 23 Sep 1775 for £50 (Natwest Archives, DR/427/71 folio 952). This may have been for a plan, as this was a typical amount he charged for this (Turnbull and Wickham 2022, 76). There was a further payment to White from ‘Thompson’ on 13 October 1777 for £60 (Natwest Archives, DR/427/75 folio 887) that may have been for supervising initial groundwork or the supply of trees. In 1776, Henry Thompson had taken out a mortgage on part of the Kirby Hall property (KULSC MT 307) perhaps to fund these works.

John died on the 18 March that year and the estate went to his son, Henry. By 1780, another designer, Adam Mickle II, may have been working on the grounds. In a letter to her mother, Lady Grantham of Newby Park noted on 21 September:

We have also had an improver of ground over, a Mr Miguel (Mickle)…originally a foreman of Mr Brown’s, now settled in this county & recommended by a Mr Thompson (a gentleman some miles from hence, who had visited here) as having done well at Ld Scarbrough’s (BA L30/9/81/5).

His son, Adam, was baptised at Little Ouseburn church on the 4 March 1781 and in the parish records, Mickle is described as a ‘planter’ so perhaps had been carrying out White’s plans for new plantations.

Mickle had only recently set up as an independent, having worked for Lancelot Brown for many years and was working at Newby Park from 1780 (BA L30/15/54/175). Concrete evidence of his involvement comes from a letter of 7 July 1784 when Lord Grantham of Newby Park wrote to his brother, Frederick Robinson, that ‘Mickle is going to work at Kirby, I believe at the Entrance’ (BA L30/15/54/231). This was the new northern entrance and carriageway through the former Berrygarths shown on the 1815 map (NYCRO PR/OUL, Figure 6) and was next to a shelterbelt of trees to the north and east. Whether a lodge was planned at the entrance is not known but the local architect, William Belwood, had been employed prior to July 1784 (BA L30/15/54/236).

In 1786, Thompson acquired the land called ‘Boat Closes’ belonging to the Cass family (MT 983-6) in the middle of his estate to the northeast (marked on the 1766 map, Figure 3), in exchange for other land he owned in Thorp Underwood. This would have enabled him to expand the designed landscape to the river if he wanted, although it remained as farmland until the mid-19th century. There was a plantation (Hawthorn Bank) created though next to the river before 1815.

The designed landscape by 1815 (NYCRO PR/OUL, Figure 6) had significantly changed since 1766 but whether this was by White, Mickle or another designer is unknown. The open parkland now covered the western side of the serpentine lake taking in the former fields of Crossfield and Brickhill Close. The northern parkland of the former Berrygarths included fields to the east and it joined up with the southern parkland. The ‘Little Wood’ had been expanded to the eastern boundary of the park with new woodland extending towards the River Ure/Ouse and a small plantation had been put in on the southwestern edge of the lake. To the north of the walled kitchen garden was a substantial building, perhaps the hothouse mentioned in 1758. Next to the paths in the pleasure grounds to the northeast of the hall, were two further buildings (NYCRO PR/OUL, Figure 7). The larger of these is labelled as a ‘Green House’ on the 1st edition 6” OS map surveyed between 1846 and 1851 (Figure 8) and is extant.

Richard John Thompson inherited the estate and substantial funds from his father in 1814. Henry Thompson appeared to have made some good investments and left over £141,000 in funds in his will with his heir receiving half and his other six beneficiaries including his other children, a 1/12th each (WYASL WYL 382/114/231).

1816 – 1892

Richard John Thompson commissioned a new lodge from Robert Lugar before 1822 and in 1834, John B. Papworth provided plans to redesign the pleasure grounds and for a fountain. The plan for the grounds (RIBA PB1340/PAP[268](1-2)) is now missing and it is impossible to say whether the design was implemented. However an area called the ‘Flower Garden’ with two fountains are shown on the OS map, surveyed c. 1851 (Figure 8). An article from 1865 described the flower garden as ‘large, and is one of the old-fashioned kind’ (The Florist and Pomologist November, 243), so could date from the 1830s.

By 1851, an icehouse had been added in the northern shelterbelt just east of the lodge, together with a second carriageway leading directly from Little Ouseburn bridge to the hall and a boat house near the garden bridge. More woodland had been created to the east including Sugar Hills Plantation and the New Plantation south of Long Plantation (Figure 9). North of the kitchen garden were a range of buildings that by 1865 included two vineries, ‘one a very large one, which has borne immense crops for a number of years. These two, we understand are to be removed’ (ibid, 242). It is likely that the large one was the freestanding building seen on the 1815 map.

Richard John Thompson died in 1853 and Kirby was inherited by his son, Harry. He expanded the hall in 1857 by adding a substantial wing and built the riding school next to the stables. It was perhaps at this time that a new lodge from the village of Little Ouseburn was constructed, with a carriageway from it crossing a new bridge over the lake to the hall. Harry Thompson made changes to the kitchen gardens including installing a new range of glasshouses along the southern wall in 1864 ‘on Sir Joseph Paxton’s principle’ (ibid). The new slip garden to the south may have been added at this time (Figure 10).

Harry Thompson was created a baronet just before his death in 1874, having added Meysey to his surname and his son, Henry Meysey, took over the estate. By 1892, the parkland now extended to the River Ure/Ouse with Long Wood surrounded by it, the lower section being named ‘Back Park’. The shelterbelt to the north, next to the public road, had been lengthened alongside the new parkland enclosing the Keeper’s House and pheasantry. The former Great Wood had been renamed ‘American Wood’, perhaps because it had been replanted with North American species (Figure 11). When these changes were carried out is not known.

Later history

After the death of Henry Meysey-Thompson’s only son in 1915, the Kirby Hall estate was put up for sale in September 1919 (NYCRO ZRR). In 1920, most of the 18th century part of the hall was demolished with just the Victorian wing surviving. By 1950, a large part of the former Long Wood had been cleared as well as the southwestern part of the American Wood but the rest of the designed landscape was largely intact (Figure 12). The former area of woodland known as Long Wood has since been replanted, however parts of the parkland have been replaced with arable fields. The estate covering the historic designed landscape was put up for sale in July 2024.

Location

Kirby Hall lies next to the village of Little Ouseburn, 5 miles (8km) southeast of Boroughbridge.

Area

The Kirby Hall designed landscape at its greatest extent in 1919 was 356 acres (144 ha).

Boundaries

The northern boundary is formed by the public road Boat Lane from the junction of Mill Lane in the east to New Road in the west, it then follows the northern edge of the lake to ‘The Island’. Its western boundary follows the lake south until just opposite Moat Hall and then continues along the public road to the New Lodge. From there Thorp Green Lane is the western boundary until SE 459 602. Its southern extent is formed by the parkland, American Wood and Round Wood until it reaches the River Ure/Ouse. The latter forms the eastern boundary until the northern edge of Hawthorn Bank and then from Sugar Hills Plantation north to Mill Lane.

Landform

The underlying bedrock is Sherwood Sandstone Group across the whole area. This is overlaid with deposits of clay, silt, sand and gravel giving rise to slowly permeable, seasonally wet, slightly acid but base-rich loamy and clayey soils with moderate fertility for most of the site. To the west of the lake, the soil is a freely draining, slightly acidic loam with low fertility.

Setting

Kirby Hall is in the Landscape Characterisation Area of Vale of York. This is characterised by a largely open, flat and low-lying landscape between the higher land surrounding it and the major rivers that ultimately flow towards the Humber. It is predominantly agricultural but with many important historic parklands associated with country houses. The hall sits on a flat piece of land c. 24m AOD with the land around it at a similar level. To the east, it rises slightly to c. 28m AOD before falling away sharply to the main river at 12m OD.

Entrances and approaches

Old Lodge [Grade II – NHLE 1150291]

The design for this appears in Robert Lugar’s book Villa architecture of 1828, plate 6. No building is shown on the 1815 map, so it is likely to have been built after this. The carriageway from the lodge to the hall was probably the one that Mickle was working on in 1784.

New Lodge [Grade II – NHLE 1150292]

Built after 1851, it provided an entrance from Little Ouseburn village. Its gates and gatepiers are listed Grade II* [NHLE 1293661] and are described as 18th century in the HE listing so may have been moved here from another location.

Gateway to former Kirby Hall [Grade II – NHLE 1190739]

The gateway, walls and carriage-gate piers forming the immediate entrance to the demolished part of Kirby Hall that was constructed between 1748 and 1755.

Principal buildings

Kirby Hall [Grade II – NHLE 1150293]

The original building was built between 1748 and 1755 to the design of Roger Morris, Lord Burlington, John Carr and Stephen Thompson (Figure 5) with an additional wing built in 1857. Only the latter remains, with the former being demolished in 1920.

Stables [Grade II – NHLE 1315398]

Main stableblock contemporary with the hall i.e. 1748-55, with later 18th century additions.

Garden building [Grade II – NHLE 1150294]

110m north of the hall is a building first marked on the 1815 map. The HE listing describes it as 18th century, probably designed by Roger Morris, Lord Burlington or John Carr.

Icehouse [Grade II – 1190707]

At SE 45543 61355, northeast of the Old Lodge, the HE listing dates it to 18th century however not shown on 1815 map, so exact date uncertain.

Little Ouseburn Bridge [Grade II – NHLE 1315437]

Current structure likely to date from 1746 – 1748, when the serpentine lake was being constructed. Possibly a design by John Carr.

Iron Bridge

Built c. 1857 to take the carriageway from the New Lodge to the hall.

Garden Bridge

Constructed between 1748 and 1766 to access the new walled kitchen garden from the hall.

Boat house

This was originally located on the southern side of the lake next to the walled kitchen garden on the 1st edition OS 6” map (Figure 7). By 1892, this had been replaced with another boat house on the northern side to the left of the Garden Bridge (Figure 9).

Gardens and pleasure grounds

Gardens of old hall

In a series of deeds (KULSC MT206-19) from 1619 to 1650, there was a reference to the manor house with ‘garden and 2 orchards adjoining’ and these were probably those seen on the 1743 map (Figure 2).

Grounds around Kirby Hall

There is no detail on the 1766 map of pleasure grounds around the new hall, however by 1815 there was an open (lawned?) area to the south of the hall and pleasure grounds to the north (Figure 7). The latter area was remodelled possibly in the 1830s and a description from 1865 referred to: ‘[its] large beds and borders…[being] planted with Roses and hardy perennials, but Geraniums and other bedding plants monopolise the greater proportion of the garden’ (The Florist and Pomologist November, 243). By 1892, there was terracing to the south and east of the enlarged hall and the northern pleasure ground had been planted with more trees including conifers (Figure 13).

Kitchen garden

This was probably constructed between 1748 and 1755 for the new hall, although it is first marked on the 1766 map. The walled section covered about 1¼ acres with a similar sized area around it that included a freestanding greenhouse by 1815 (Figure 7). By 1851, there was a range of (service?) buildings on the northwestern wall, with perhaps the peach trees under a glass case with no heat detailed in 1858 (The Florist, Fruitist, and Garden Miscellany, 22). In 1864, a large new range of glasshouses was built on the southern wall and a detailed description was given of it the following year:

‘We found Mr. Purchase [head gardener] in the new range of houses, erected here about eighteen months since, on Sir Joseph Paxton’s principle. The range is 400 feet long, divided into eight compartments. Entering the range at the east end, the first house is an orchard-house; all the trees are planted out; they are Cherries, Apricots, and Plums, and were in the highest possible state of health and cleanliness…The next house is also an orchard-house, and the trees are all planted out…The next house is a Peach-house. The trees are planted to root out into the outside border, and the branches are trained to trelliswork as in an ordinary Peach-house; but the trelliswork is kept low enough to allow the sun to reach the back wall, against which trees are also planted. This house, like the others, is heated by hot water…We understand the hot-water work was done by Messrs. Jones & Sons, of Bankside. The next house is a plant-stove…There is a break in the range here, a walk from the enclosed garden leading through to the outer garden. Going onwards through the range the next house we entered was a greenhouse…the other three houses are vineries. All the best kinds of Vines have been planted (The Florist and Pomologist November, 242-3).

The older greenhouses were removed in the late 1860s and the area was landscaped by 1892 (Figure 10). Another glasshouse was added to the central section, together with a range on the northeastern wall that may have been the early vinery and early peach house referred to in 1865 (ibid). The walls remain and are listed on the HE Register (NHLE 1190850), together with the former gardener’s cottage and bothy.

Park and plantations

Park

It is possible that Berrygarths, covering nearly 28½ acres, was designed as proto-parkland in the early 18th century. By 1766, a defined area called ‘The Park’ of 57 acres had been created to the east. An area to the west of the water was added before 1815 (83 acres) and the former Berrygarths had expanded to just over 44 acres. Further expansion in the 19th century meant by 1919, the parkland covered 220 acres (NYCRO ZRR).

Great Wood/American Wood

Extant by 1743, it may have been planted in the late 17th or early 18th century as no mention is made of it in early documents and evidence of ridge and furrow on lidar showed that it had been cultivated previously. Originally 14 acres, it changed little in overall size despite small sections being added to the south and southwest. Now only a small southern section remains.

Little Wood

Its original 6 acres in 1743 had decreased to 5 acres by 1815 and had been felled by 1950.

Long Wood

Created by 1815, this was next to the eastern edge of Little Wood. It covered 42 acres at its greatest extent in the late 19th century but a large section to the west was removed in the first half of the 20th century. This has since been replanted.

Sugar Hills Plantation

In place by 1851, this woodland of over 11½ acres is still extant.

Hawthorn Bank

Next to the river, part of this was on land acquired by Henry Thompson from the Cass estate in 1786, so dates from between then and 1815. Covering about 12 acres, it is still in place.

Northern shelterbelt/Boat Lane Plantation

The western section may well date from c. 1784 when Mickle is reported to be working at the ‘entrance’. It was extended eastwards in the second half of the 19th century. Originally 5½ acres, just the later eastern part remains.

Water

The Ouse Gill Beck was a natural stream that flowed to the confluence of the Rivers Ure and Ouse. By 1743, it had been dammed to two places to create a large pond next to Great Wood and another to form a race for the watermill. In 1747, Stephen Thompson decided to make the section from north of Little Ouseburn church to the mill a wider ‘river’ or serpentine lake. It was completed a year later and its earthworks remain.

Books and articles

Henrey, B. 1986. No ordinary gardener: Thomas Knowlton, 1691-1781. London, British Museum (Natural History).

Michelmore, D.J.H. 1981. Fountains Abbey Lease Book. Leeds, Yorkshire Archaeological Society.

Turnbull, D and Wickham, L. 2022. Thomas White: redesigning the northern British Landscape. Oxford, Windgather Press.

Primary sources

Bedfordshire Archives (BA)

L30/15/54/175 Letter from Lord Grantham, Newby to Frederick Robinson, 24 October 1780

L 30/15/54/231 Letter from Lord Grantham, Newby [Park] to Frederick Robinson, 7 July 1784

L30/15/54/236 Letter from Lord Grantham, Newby Park to Frederick Robinson, 14 Jul 1784

L30/9/81/5 Letter Lady Grantham to Jemima Yorke, 21 Sep 1780

East Riding Archives (ERA)

DDGR/41/3/7 Letter from Stephen Thompson to Thomas Grimston, 7 Mar 1746

DDGR/41/3/10 Letter from Stephen Thompson to Thomas Grimston, 17 June 1746

DDGR/41/3/17 Letter from Stephen Thompson to Thomas Grimston, 22 Nov 1746

DDGR/41/5/2 Letter from Stephen Thompson to Thomas Grimston, 3 Jan 1747

DDGR/41/5/5 Letter from Stephen Thompson to Thomas Grimston, June 1747

DDGR/41/5/9 Letter from Stephen Thompson to Thomas Grimston, 26 Mar 1748

DDGR/41/5/10 Letter from Stephen Thompson to Thomas Grimston, 21 Apr 1748

DDGR/41/5/16 Letter from Stephen Thompson to Thomas Grimston, 10 May 1748

DDGR/41/5/19 Letter from Stephen Thompson to Thomas Grimston, 20 Jun 1748

DDGR/41/6/19 Letter from Stephen Thompson to Thomas Grimston, 20 April 1749

DDGR/42/5/37 Letter from Stephen Thompson to John Grimston, 14 Sep 1755

Keele University Library Special Collections (KULSC)

MT 196-9 4 deeds re ½ manor of Kirkeby hall [Kirkeby Usborne) with (named) closes between Sir Thomas Wharton (QC) and John Dickinson [Dyconson] of Kyrby Hall, yeoman, 1556

MT 200-1 Letters Patent to Sir Thomas Middleton and Richard Swale of Greenhammerton, manor of Kirkby Hall, 1616

MT 205 Inquisition of William Dickonson, snr., and William Dickenson, jnr., both of Kirkbie Hall , yeomen, re property in Kirkeby Hall, and Thorpunderwood, 1619

MT 280-94 15 deeds and related papers re settlement of the debts of Thomas Dickinson of Kirby Hall to Francis Wheelwright of Helmsley, the Dean and Chapter of York and Henry Hitch of Leathly, 1659-84

MT 307 Mortgage between Henry Thompson and Robert and William Atkinson, 1776

MT 934 Faculty to Henry Thompson, esq., parishioner and inhabitant of Little Usburne [Ouseburn], to build a burial vault, 1742/3.

MT 983-6 3 deeds and abstract of title for exchange of lands between George Henlock of Great Ouseburn and Henry Thompson, 1786.

North Yorkshire County Record Office (NYCRO)

PR/OUL Great and Little Ouseburn map (estate of RJ Thompson), 1815

ZRR K Estate Maps of Kirby Hall 1743 & 1766

Sale catalogue of Kirby Hall 1919

Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA)

PB1340/PAP[268](1-2) J.B. Papworth, Kirby Hall (Yorkshire): Design for a fountain and for the laying out of part of the grounds, 1834 [missing from archive since 2002]

West Yorkshire Archive Services Leeds (WYASL)

WYL382/114 [230-231] Account Books of the executors of the will of Henry Thompson Esq. of Kirby Hall, 1814-1849

Maps

Ordnance Survey 6” 1st edition, surveyed 1846 to 1851, published 1853

Ordnance Survey 25” 1st edition, surveyed 1892, published 1893

Ordnance Survey 6” revised edition, revised 1907, published 1910

Ordnance Survey 6” SE46 – C revised edition, revised 1950-1, published 1961

Figure 1 – Kirby Hall estate belonging to Henry Thompson in 1743. North Yorkshire County Record Office (ZRR K [1743])

Figure 2 – Kirby Hall estate belonging to Henry Thompson in 1743, detail of hall and gardens. North Yorkshire County Record Office (ZRR K [1743])

Figure 3 – Kirby Hall estate belonging to John Thompson in 1766. North Yorkshire County Record Office (ZRR K [1766])

Figure 4 - John Donowell (active 1753–1786) A View of the Back Part of the Cassina, & Part of the Serpentine River, terminated by the Cascade in the Garden of the Earl of Burlington, at Chiswick. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1995.13.165. Public domain.

Figure 5 - Kirby Hall print by James Basire, c. 1767. Courtesy British Library, Maps K.Top.45.24.1.

Figure 6 – Kirby Hall estate showing new plantations and parkland, 1815. North Yorkshire County Record Office (PR/OUL)

Figure 7 – Kirby Hall gardens and kitchen garden, 1815. North Yorkshire County Record Office (PR/OUL)

Figure 8 – Kirby Hall pleasure grounds and flower garden from Ordnance Survey 6” 1st edition, surveyed 1846 to 1851, published 1853. National Library of Scotland CC-BY.

Figure 9 – Kirby Hall estate from Ordnance Survey 6” 1st edition, surveyed 1846 to 1851, published 1853. National Library of Scotland CC-BY.

Figure 10 – Kirby Hall kitchen garden from Ordnance Survey 25” 1st edition, surveyed 1892, published 1893. National Library of Scotland CC-BY.

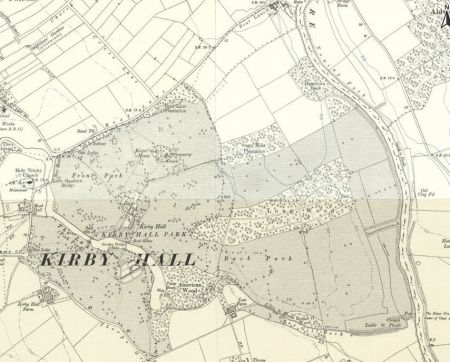

Figure 11 – Kirby Hall estate from Ordnance Survey 6” edition, revised 1907, published 1910. National Library of Scotland CC-BY.

Figure 12 – Kirby Hall estate from Ordnance Survey 6” edition, revised 1950-1, published 1961. National Library of Scotland CC-BY.

Figure 13 – Kirby Hall pleasure grounds from Ordnance Survey 25” 1st edition, surveyed 1892, published 1893. National Library of Scotland CC-BY.