Tucked away in the northern suburbs of Leeds is Gledhow, which has a long and interesting landscape history. The Gledhow estate is part of the wider area known as ‘Allerton’ or ‘Chapel Allerton’, to the north of Leeds. The spa or spring (on which the bath house is built) is in Gipton, which has often been a separate landholding in its history. The name Gledhow is thought to derive from old English: hill (how) of the kite (gled).

Early history

The first evidence we have is of a late prehistoric enclosed settlement in Gipton Wood from around 1000BC [1]. This may be the Saxon fort that the early 18th century antiquarian, Ralph Thoresby, claimed to have found. In 1066, according to the Domesday Book, the owner of (Chapel) Allerton was the Saxon lord, Gluniairnn. Gipton has two entries and was owned by Earl Edwin and Gospatric. By 1086, both were owned by the Norman, Ilbert de Lacy. While Gipton had 3.7 households, Allerton had none but both paid a relatively large amount of tax! [2] This must have indicated the value of these lands.

The de Lacy family made grants of land to nearby Kirkstall Abbey from its foundation in 1152 (Kirkstall was founded by Henry de Lacy). By the early 13th century, this would appear to have included Allerton [3]. By the time of the dissolution of the monasteries, the lands belonging to Kirkstall came to the Crown in 1539 and this included the manor of Chapel Allerton. By the late 16th century, the Thwaites family were living in Gledhow [4], presumably as tenants.

17th century

In 1601, the Crown sold the Manor of Chapel Allerton to four parties: Thomas Kellingbeck, Thomas Marshall, John Thwaites Senior and John Fladder for £258 10s 11½d [5]. Thwaites had bought the Gledhow estate part and he (or his son, also John) built the first Gledhow Hall and developed the surrounding lands. John Jnr became Alderman of Leeds in 1653: the first of many owners of the estate to hold that position (the forerunner of Mayor).

John Thwaites died in 1671 and the estate passed via his daughter to the Waddington family. Her eldest son, Edward, is credited with erecting a bath house on the site of the Gipton spa in that year. Whether this was the first is unknown but the spring is mentioned in a survey for James I in 1612. We also do not know why he built it but it must have been of significance to him as the present building (Figure 1) has the plaque with the inscription:

‘HOC FECIT

EDVARDUS WADDINGTON,

DE GLEADOW

ANNO DOMINI 1671’

Photograph: Louise Wickham.

Sadly three years later, Edward died aged only 24. The estate appears to then pass to his next three brothers. The first was Samuel who died in 1681, unmarried, as did John, his next brother, later that year. [6] So it finally went to Benjamin. With Benjamin’s death in February 1690, Gledhow passed to his only daughter, Jane, who was three years old. [7]

18th century

Jane Waddington married Sir Roger Beckwith of Aldburgh on 10 October 1705. None of their children were baptised in Leeds, so possibly they were living on Beckwith’s estate in North Yorkshire. Jane died and was buried at Masham in 1713. However, the spa seemed to be popular with Ralph Thoresby noting in his diary on 5 July 1708 [8]:

Walked with my dear by Chapel-town and Gledhow to Gypton-well (whence my Lord Irwin, who comes thither in his coach daily, was but just gone) to enquire for conveniences for my dear child Richard’s bathing.

In his publication of 1715 [9], Thoresby comments:

At this Place a very curious cold Spring, which in a Romish Country could not have miss’d the Patronage of some Saint: ’Tis of late Years accommodated with convenient Lodgings to Sweat the Patient after Bathing, and is frequented by Persons of Honour, being reputed little or nothing inferior to St. Mongah’s. Over the entrance is inscrib’d,

HOC FECIT

EDVARDUS WADDINGTON,

DE GLEADOW

ANNO DOMINI 1681 (sic)

By the 1730s, the estate was sold to the Sleigh family: possibly Hugh Sleigh who was a noted attorney in Leeds and ‘greatly improved the old house’ [10]. His only daughter, Ann, had married Hugh’s apprentice, Henry Pawson, in 1723. It was their daughter (Anne) who sold Gledhow to Jeremiah Dixon in 1764, following the death of her husband. She had married William Wilson, a London merchant, in 1759. Wilson became the second Mayor (Alderman) of Leeds to occupy Gledhow Hall in 1762.

Photograph: Louise Wickham.

Photograph: Louise Wickham.

Jeremiah Dixon remodelled the Hall (Figure 2), which has been attributed to Carr of York, possibly after a fire in 1769 [11]. In 1768, he built the bridge over Gledhow Lane to the pleasure gardens. Still extant here is a so-called ice-house (Figure 3). Although possibly from this period, its position and design would suggest that it was used for other purposes.

Dixon was also responsible for the large scale plantations that are the basis of the woods we see today. He introduced the Swiss or Aphernously Pine which became known as the Gledhow Pine (Pinus cembra) [12]. It is said that they were propagated from cones procured direct from Switzerland [13]. Dixon purchased the Manor of Chapel Allerton from the Killingbeck family in 1765 and in 1771, he added to his landholding by purchasing the estates belonging to Lady Dawes and her son [14] (Lady Dawes had married Beilby Thompson as his second wife: his first wife being Jane Beckwith, youngest daughter of Sir Roger and Jane, née Waddington).

Dixon also built ‘King Alfred’s Castle’, also supposedly from a design by John Carr, on Tunnel How Hill (between Stonegate Road and the Ring Road) on what was reputed to be the highest point in Leeds (Figure 4). A stone plaque was set in the wall of the 'castle' which read: 'To the memory of Alfred the Great, the pious and magnanimous, the friend of science, virtue, law and liberty. This monument Jeremiah Dixon of Allerton Gledhow caused to be erected.' A date is also quoted as 1720 but it is more likely to be 1770. It collapsed in May 1946 when one of two walls that contained an arched doorway fell in. [15] It is in a direct line from the Hall, so it may have originally been visible from there.

By kind permission of Leeds Libraries.

With Jeremiah’s death in 1782, the estate passed to his eldest son, John. He divided his time between Gledhow and his estates in Cheshire. His second son, also Jeremiah, became the third occupant to become Mayor in 1784.

19th century

Between 1812 and 1815, Turner sketched the view of the Hall from across the valley [16] and made a painting as shown in the back of the last YGT Newsletter. An engraving by G Cooke was published in 1816 (Figure 5) for Dr Whitaker’s History of Leeds.

John Dixon died in 1824 and was succeeded by his son, Henry. However the Gledhow estate was occupied by Sir John Beckett from 1822 and then by his widow after his death in 1826. [17] Lady Beckett died in 1833 and two years later, Thomas Benyon, a flax merchant is the new owner [18]. By this stage, the bath house seems to have fallen from favour given the comment from Edward Parsons that: ‘the waters of Gipton have lost their celebrity and are no longer frequented’ [19].

The 1846 Tithe map shows the estate now split with William Hey and James Brown, owners of Gledhow Wood (and the spa) and Benyon, the Hall and surrounding pleasure gardens. William Hey was from a family of distinguished surgeons based in Leeds (and both his father and grandfather were Mayors). Possibly as a retirement home, Hey built Gledhow Wood House c1860. [20] James Brown was the first cousin of Benyon’s wife and was the owner of the neighbouring property of Harehills Grove.

Reproduced with the permission of Special Collections, Leeds University Library, YAS/MS1790/234.

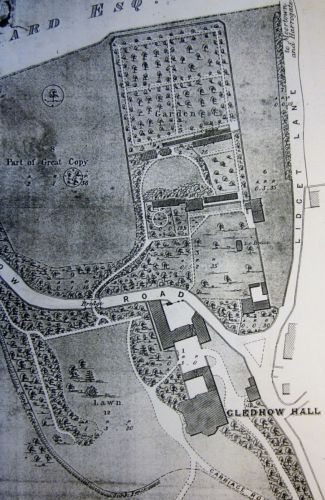

Benyon’s business depended on linen and canvas for ship’s sails. Unfortunately he went bankrupt in 1861 and Gledhow Hall was bought by John Cooper, a cloth merchant. Inherited by his brother, William, in 1870, the Hall was once again up for sale after the latter’s death in 1873. The Hall, pleasure and kitchen gardens are shown in detail in Figure 6 from the sale plan of 1878 [21]. At this time, the estate was already being enjoyed by the public as the lake, known as Benyon’s Pond, was popular as a place for skating ‘by the upper and middle classes of Leeds’ [22].

The next owner was Samuel Croft, who was Mayor in 1875. After Croft’s death in 1883, it was bought by the first Lord Mayor, James Kitson (1st Baron Airedale), an industrial magnate and MP. Gledhow Wood House was put up for sale on William Hey’s death also in 1875 [23] and was bought by Edward Schunck, a merchant.

In 1884, the ‘Gledhow estate’ contained [24]: an orchard, shrubbery, ice house, well, peach house, flower and kitchen gardens, glass pits (cold frames?), fernery, greenhouses, conservatory, vineries, stoves and potting sheds. Most notably in the house, a Burmantofts ‘Faience’ bathroom was installed for the proposed visit of the Prince of Wales in 1885.

The two estates are united in a way when Albert Ernest Kitson (James’s son) and Florence Schunck (Edward’s daughter) married in 1890. Perhaps the bath house was rebuilt at this time, as a report from 1885 has the description: ‘On the left, from Leeds, of the road which passes through Gipton Wood, there is still an old well, protected by rude walling, with a long flight of partly broken steps down to it. The building has gone and with it the stone that bore the name, "Edwardus Waddington”’. [25]

20th century

James Kitson died in 1911 and the estate seems to have been put in trust for his sons [26]: Albert Ernest, Edward Christian and Roland Dudley. In the 1911 census, Edward (and his wife) and his sister, Alice Hilda, are recorded as living there. The OS Map from c1910 shows a more simplified layout to the main gardens. It was though noted for its fuchsia garden (‘My Lady’s Garden’ – Figure 7) and a topiary in the shape of an ‘old-fashioned rush-bottomed chair’ [27].

Photograph: (Plate XLVIII) from The Gardens of England in the Northern Counties by Charles Holme (1911, The Studio Limited, London & New York). University of California Libraries.

During the First World War, the house was used as a military hospital. Hilda moved to Gledhow Grange and Edward to Quarry Dene, Westwood. Edward died in 1922 and it seems that at this point, the estate starts to be broken up and sold off. The Hall comes into the possession of Leeds Council from 1923 and becomes a school. The creation of the Gledhow Valley Road divides the estate in 1926. The Wades Trust acquires part of Gledhow Woods in November 1927 and March 1928. In 1948 and 1956, work was done to improve the area, creating paths and enlarging the lake.

Before Hilda’s death in 1944, she gave £200 for the Council to preserve the bath house. However it was not until 2004 that the Friends of Gledhow Valley were able to get it fenced off and properly protected.

References / Bibliography

[1] http://www.pastscape.org.uk

[2] http://domesdaymap.co.uk [consulted 7 August 2012]

[3] E. Clark (1895) The Foundation of Kirkstall, Publications of the Thoresby Soc. IV, Leeds, pp180-1

[4] Baptismal record of John Thwaites, christened on the 3rd January 1587 at St Peter’s, Leeds. His father, also John, is described as ‘of Gledhow’

[5] T. Allen (1831) A new and complete history of the county of York, Volume 4, London: I T Hinton, p466

[6] St Peter’s, Leeds parish records

[7] St Peter’s, Leeds parish records

[8] Ralph Thoresby (1830) The Diary of Ralph Thoresby, London: Colburn & Bentley, p8

[9] Ralph Thoresby (1715) Ducatus Leodiensis, 1st ed., London: Maurice Atkins, p113

[10] Edward Parsons (1834) The civil, ecclesiastical [&c.] history of Leeds, Halifax, Huddersfield ... and the manufacturing district of Yorkshire, Leeds: Frederick Hobson, p199

[11] St. James's Chronicle or the British Evening Post, Tuesday 7 to Thursday February 9, 1769

[12] J. C. Loudon (1838) Arboretum et fruticetum Britannicum, London: Longman & Co, p2278

[13] Arthur Aikin (1804) The Annual review and history of literature for 1803, Volume 2, London: Longman and Rees, p885

[14] Rev. R. V. Taylor (1865) The biographia leodiensis or, Biographical sketches of the worthies of Leeds and neighbourhood, from the Norman conquest to the present time, London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co, p182

[16] https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-gledhow-hall-near-leeds-d09857

[17] Edward Parsons (1834) The civil, ecclesiastical [&c.] history of Leeds, Halifax, Huddersfield ... and the manufacturing district of Yorkshire, Leeds: Frederick Hobson, p199

[18] Poll book for 1835

[19] Edward Parsons (1834) The civil, ecclesiastical [&c.] history of Leeds, Halifax, Huddersfield ... and the manufacturing district of Yorkshire, Leeds: Frederick Hobson, p200

[20] West Yorkshire Archives – ref WYL160/M404

[21] Yorkshire Archaeological Society Archives – ref MS1790/234

[22] The Penny Illustrated Paper, 4 February 1865, reported the sad case of a pair drowning after falling through the ice.

[23] West Yorkshire Archives – ref WYL160/M4

[24] Deeds for “Lochmaben”, 149 Gledhow Valley Road

[25] Ralph Thoresby, the topographer; his town and times, R. H. Atkinson, 1885, Leeds: Walker and Laycock, p132

[26] Deeds for “Lochmaben”, 149 Gledhow Valley Road

[27] The Gardens of England in the Northern Counties, special Spring number of the Studio, 1911