The Frankland family held Thirkleby for over 300 years and shaped the designed landscape following the fashionable ideas of the time. William Frankland, 1st Baronet began the enclosure of Great Thirkleby in 1668 that allowed his son Sir Thomas (2nd Bt) to create a park and admired formal garden between 1699 and c. 1720. These surrounded the first Hall that dated to the late 16th or early 17th century. When Sir Thomas (6th Bt) inherited in 1784, both the house and the designed landscape were out of fashion. He demolished the old hall and commissioned the architect James Wyatt to build a new hall with associated buildings on higher ground to the northwest.

Adam Mickle II was employed to lay out the ground in the same year. Sir Thomas had a great interest in horticulture and had a major influence on the design and plants grown. This interest continued during the tenure of his son, Robert Frankland Russell (7th Bt) and daughter-in-law, who enlarged the Hall and further developed the grounds. Their grandson, Ralph Payne-Gallwey, was the last of the family to live at Thirkleby. A keen sportsman, he was responsible for the creation of the Lake, along with other ponds and a duck decoy elsewhere on the estate. In 1927, the Hall was demolished but Wyatt’s stables, lodge and the shell of the walled kitchen garden remain along with much of the landscaping including the lake and plantations.

Estate owners

In 1066 Thirkleby was held by Kofse as part of Coxwold and passed to Hugh son of Baldric in 1086 (https://opendomesday.org/place/SE4778/thirkleby/ accessed 26 January 2020).

It subsequently came under the overlordship of the Mowbrays following the descent of the manor of Thirsk, being held successively by William de Busci/Buscy, Sir Thomas Ughtred, Sir Roger Fulthorpe and heirs until the 16th century when Queen Elizabeth granted the manor of Great Thirkleby to the Earl of Warwick in 1576. He alienated it to William Frankland, a wealthy member of the Clothworkers Company (https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/north/vol2/pp55-58 accessed 17 January 2019).

The estate remained in the hands of the Frankland family and their descendants until 1927. William Frankland (1640-1697) was created 1st Baronet Frankland, of Thirkleby on 24 December 1660 by Charles II. Thereafter the estate passed to Sir Thomas Frankland 2nd Baronet (1663-1726). His son Sir Thomas Frankland 3rd Baronet (1685 - 1747) died without male issue and left the estate absolutely to his second wife. The will was contested successfully by his successor to the baronetcy, his nephew Sir Charles Henry Frankland 4th Baronet (1716 - 1768), but the widow retained possession of the estate for her lifetime (https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/north/vol2/pp55-58 accessed 17 January 2019).Sir Charles never occupied Thirkleby as he predeceased the widow who died in 1783. His brother and successor Admiral Sir Thomas Frankland 5th Baronet (1718 - 1784) only came into possession of Thirkleby the year before he died (Clay 1899, 243-248).

His son Sir Thomas Frankland 6th Baronet (1750 - 1831), was responsible for the building of the new Hall and remodelling of the Park. Sir Thomas was succeeded in 1831 by his son Sir Robert Frankland Russell, 7th Baronet (1784 - 1849). He adopted the name Russell as a condition of the inheritance of Chequers Court in Buckinghamshire.

After Sir Robert’s death in 1849, both the Thirkleby estate and Chequers remained in the hands of his widow, Lady Louisa Frankland Russell, though the title went to another branch of the family (https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/frankland-robert-1784-1849 accessed 30 January 2020).

The estate passed to Sir Robert’s daughter Lady Emily Payne-Gallwey. She and her family had moved to Thirkleby in 1855 and she adopted the name Payne Frankland in 1882 after her husband’s death in line with her mother’s wishes, apparently to ensure her inheritance of Thirkleby.

Her son Sir Ralph William Payne-Gallwey (1848 - 1916) resided in Ireland before his father’s death but moved to Thirkleby after 1882. Lady Emily died in 1913 and the estate passed to Sir Ralph who changed his name to Payne-Gallwey-Frankland in 1914. He was the last Frankland to live at Thirkleby as his only son was killed in the First World War. He died in 1916 and the estate passed to his nephew Lieutenant Sir John Frankland Payne-Gallwey who later sold it off in the 1920s (NYCRO ZKC 27).

Key Owners responsible for the major developments of the designed landscape and dates of their involvement:

Thomas Frankland 2nd Baronet (1697-1726)

Thomas Frankland 3rd Baronet (1726-1747)

Sir Thomas Frankland 6th Baronet (1784-1831)

Sir Robert and Lady Louisa Frankland Russell (1849-1871)

Lady Emily & Sir William Payne Gallwey (1855-1913) & son Ralph Payne Gallwey (c1882-1919)

Early history of the site

In 1086 Thirkleby (Turchilebi) was in the 40% of smallest settlements being estimated to have 7.7 households (https://opendomesday.org/place/SE4778/thirkleby/ accessed 26 January 2020).

By 1301 26 households were subject to tax, and one Rogero de Burton was paying the most, 28s 3d (Brown 1897, 81-88). In 1308, Roger Burton held a ’capital messuage’ possibly a precursor of the old hall at Thirkleby which was replaced in the 18th century. In 1363, Sir Thomas Ughtred obtained a grant of free warren, giving him the right to hunt in his demesne lands in Thirkleby, which implies surrounding woodland which is also mentioned in Domesday. Subsequently several generations of the Fulthorpe family held the manor and had a ‘mansion house’ there (Brown 1909, 95-6). A mill is mentioned in the 16th century (https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/north/vol2/pp55-58#h3-0003 accessed 9 March 2020).

Chronological history of the designed landscape

Late seventeenth century

The park shown adjacent to the name Thirlesby [Thirkleby] on the Speed map of 1610 abuts the Cod Beck and lies clearly west of Bagby, so cannot be certainly identified with that at Thirkleby. The Blaeu map of 1645, thought to be based on Speed, shows what is presumably the same enclosed park a little further east, though Thirkleby is not named.

The early mansion house, dating from sometime between the sixteenth and mid seventeenth centuries, stood close to the church and village, the location being marked on later Ordnance Survey maps. It is visible today as an area of uneven ground (NYCC HER MNY56). A handwritten note in the margin of a copy of Gill’s Vallis Eboracensis states ‘it was built to st(and) near the Church The mounds + gar(den) may still be trac(ed) 1861’ (Gill 1852, 337). The house and the church stood alongside each other at the end of a continuation of the present village street, visible on the ground as a holloway, and which can be traced on the LIDAR image (Figure 1).

Enclosure of commons wastes and moors, particularly to the south and west of Great Thirkleby, was underway by 1668 even before William Frankland 1st Bt. inherited in 1672 (Atkinson 1886, 166), though pre-enclosure fields of ‘part of the Lordship of Great Thirkleby’ were still in use in 1699 and also in 1708, when the earliest documentary reference to a park occurs (LUSC/ DD94). Sir William may possibly have started the process of emparking, though it continued after his son inherited (see below).

Sir William was probably responsible for laying out the landscape features referred to in the survey of 1699: ‘The mansion house & orchards Long Walks and Pott Garths’ covering an area of 15a 2r 8p (c. 6.29 hectares) and ‘The Wood’ 16a 1r 13p (c.6.61 hectares). A further survey of a similar or slightly later date mentions ‘The Avenue’ 6a 3r 10p (2.76 hectares) and ‘Ox Close Plantation’ 2a 0r 3p (0.82 hectares) (LUSC/DD94).

The orchards are likely to correspond to one of the features on the LIDAR image which appears to show rectangular enclosures around the site of the hall, partly surrounded by relict watercourses. The location of The Wood and Ox Close Plantation are not known but The Avenue probably corresponds to one of the Long Walks. These, a feature of Stuart garden style, are likely to be similar to those at Escrick and elsewhere and to correspond to the three avenues shown on the later Jeffery's map, radiating out from the hall (Figure 2).

There were probably pleasure gardens, with flowers, around the house as John Gibson thanks Sir William Frankland in 1686 for his ‘fine flowers’ and offers to send him ‘some anemone, the double scarlet, the carnation or blue, both single, or the double star anemone, red, green and white’. He also encloses a receipt for gooseberry wine suggesting that these were produced. (RCHM 1900, 63).

Early eighteenth century

The above surveys were carried out in the early years of the tenure of Sir Thomas Frankland 2nd Bt. The first reference to a Park and a Park wall occurs in 1708 - ‘that part of Mil Field which is inclosed in the Park …also that taken up by the Way on the outside of the Park Wall’ (LUSC/DD94). The same document mentions that the wall was built in 1711. In 1699 the Mill Field, probably extending between the mill and the house, is given as 44 acres, the part enclosed being either part of the later East Park on the tithe map (Figure 3) or where there is an eastward bulge towards the village on Jeffery's map. Both areas have a lane on the outside of the park.

Sir Thomas Frankland retired from public life in 1718, so was possibly more involved in improvements at Thirkleby after that date. The Park was probably largely laid out and enclosed sometime before 1720 when it appears on the Warburton map. This shows the property straddling the Thirkleby beck but there is no other evidence that this was ever the case, as the beck had divided the separate holdings of Great and Little Thirkleby since the fifteenth century (https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/north/vol2/pp55-58 accessed 17 January 2019). A rental of 1718 lists ‘Sir Thomas Franklands house and gardens, Church Field, avenue, Oxclose and Park plantation wood’ for which the tithes were £30 (LUSC/DD94). A park is implied here but not listed separately.

Sir Thomas rebuilt the adjacent church in 1722 (Grainge 1859, p193) and it is possible that he or his son intended further improvements as plans were commissioned from Nicholas Hawksmoor sometime before 1736 (Downes 1953 334 & note 19). However the plans were apparently not implemented. The house is described as old in 1728 (CBS D-X1069/1/2) and in 1784 had a footprint of approximately 97’ x 70’ (30 x 21 metres) as depicted in a measured plan, annotated ‘Chamber Floor at Thirkleby as taken possession of by my Father 1783’ (LUSC/DD94). Ancillary buildings included brewhouse and stables (LUSC/DD94; NYCRO Z114). There is no evidence that the stables were rebuilt although there is an undated elevation for a stable building attributed to Nicholas Hawksmoor in the Payne Gallwey archives (LUSC/DD94).

In the pleasure gardens the Long Walks were retained as they are still extant in 1771 (Figure 2) but a new feature was a Wilderness described in 1812 as being ‘about 100 years old’ and planted with Ilex and possibly also beech, lime, sycamore and horse chestnut (LS JES/COR/15/44).

In 1724 John Macky wrote:

A Stranger ought not to leave Yorkshire without seeing Sir Thomas Frankland's Seat at Thirtleby [Thirkleby] near the little Town of Thirsk both for its Situation and the Fineness of its Gardens. The Parterre is incircled with Columns of Yew, the Wilderness is very neat and from the whole there is a delicious Prospect of the adjacent Country’ (Macky 1722, 2:216).

It is possible the parterres and walks included statuary like those in a property Sir Thomas had in Chiswick (Macky 1722, 1:73). There is a later reference to statues at Thirkleby as a payment was made in 1763 for ‘six men helping my man to carry the statues into the stable’, possibly because they had fallen out of fashion by that time (NYCRO Z114).

It is likely that the main changes to the gardens were carried out before the death of the 2nd Baronet in 1727 but it is also possible that the 3rd Baronet continued developments. His library, albeit inherited from his father, contained over 70 works on landscaping (Cousins, 2011, 156 & 177, note 106).

In 1728, John Baker describes the garden in his diary:

Dined this day at Sr Thomas Franklands, viewed this morning his plantation. His house is old and but indifferent & very small, the Garden being well planted with Yews and there being severall shady walks makes ?this/it very pleasant, is situated in a fine fruitfull Country & has a very [sic] prospect all round his house (CBS D-X1069/1/2).

Sir Thomas (3rd Bt) employed William Adcock, a founder member of the Ancient Society of York Florists, as a gardener at Thirkleby in 1740 and 1741. Adcock later moved to Whixley (Harvey 1974, 69). After the baronet’s death in 1747 James Rutherford ‘gardiner’ was paid 17/- (NYCRO ZPN 3/2).

Between 1758 and 1776, estate accounts show that the the third Baronet’s widow maintained the property. Park wall and pales were regularly repaired, gate hoops, crooks and catches were made by the blacksmith in 1759 and a new wooden gate was made in 1770. The same year a double ditch was dug ‘to keep the deer out of the Meadow Park’ (NYCRO Z114). Deer were kept at Thirkleby in the late 18th century as shown by the letters of the steward of Upsall Castle, who was charged in 1780 with acquiring a buck and a doe for a customary payment. He tried several properties including Thirkleby where ‘the severe winter ruined their brood’ (NYCRO ZT 6/1/1). It is not certain where the Deer Park and the Meadow Park were, though there is a small enclosure labelled Deer Park on the tithe map of 1844 (Figure 3).

By 1771 (Figure 2) the property comprised a park of approximately 75 hectares (185 acres) with the church and house close to the edge of the village, as discussed above. Three avenues (Long Walks) lead west, south and north, the south and the west avenues extending beyond the boundaries of the park. The line of the southern avenue survives today and is probably the one referred to in a later source as ‘a magnificent ancient avenue of Scotch Firs considered one of the finest in this part of the kingdom; - a worthy approach to a noble mansion, and a splendid record of the “olden times”’ (Gill 1852, 337).

1785 - 1815

Following his accession to the estate, Sir Thomas Frankland 6th Bt took the decision to make the major changes which gave it the overall form that is recorded on the Greenwood Map (surveyed 1817 & 1818 and corrected 1834) and later Tithe and 1st edition Ordnance Survey 6” maps (Figures 3 & 4). The work was largely carried out between 1785 and around 1798 and certainly by the time a survey of the Thirkleby estate was carried out in 1815 (NYCRO ZPE).

In January 1785 he is ‘pulling down Thirkleby (the old hall) and changing the situation of the house gradually’ (BARC: L 30/15/54/237) and by December he has a plan of the projected Thirkleby Place (BARC: L 30/15/54/294, 295, 296, 297). In the event the house was designed by James Wyatt: ‘I have an excellent house - built by myself (under James Wyatt) in a very fine and commanding situation’ (LS JES/COR/15/40). The new location was upslope from the old hall, away from the church and village, and more exposed to wind as his wife later complained: ‘Lady F, as usual, declaimed on the superior wisdom of our Ancestors in placing their houses low + my folly in building on a hill’ (LS JES/COR/15/56)

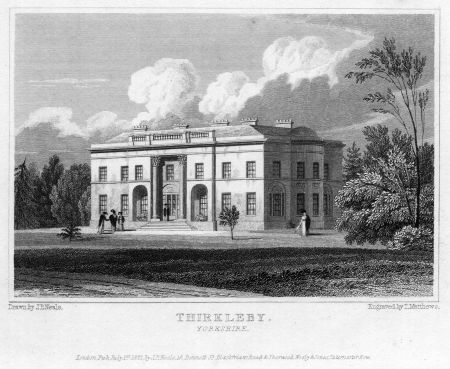

Some of Wyatt’s working drawings are held by the RIBA library and variously dated from 1787 to 1792 (RIBA SB72/8,1-27; SB96/9,28-48). The house itself can be seen in a print of 1820 and is described as ‘a handsome mansion…with a fine white stone’ (Neale & Moule 1820; Figure 7).

As well as the hall, the RIBA drawings include plans for a Kitchen Court, Stables, Lodge and Poultry House. The Stables, which survive today, were built at the same period. The terrace on the east side of the square stable block, visible on the tithe map, was possibly original to Sir Thomas’ design. This, with a small square building at each end, was linked to the house by a curvilinear boundary.

The new approach from the Thirsk road and the lodge which was built in 1792 (Grainge 1859, 193; Figures 5 & 6) lay in an extension of the park over the parish boundary into Bagby to the north. The new entrance drive was bordered by a linear plantation (later known as The Stripe) which abutted this northern boundary. This plantation, along with Oak Wood and Ruddings Wood were probably newly planted as part of the remodelling, as they do not appear on Jeffery's map.

There are also a number of drawings that relate to other sites but which may be ‘off the peg’ ideas for other buildings planned for Thirkleby. These were a piggery (1790), ice house (1795) and grape house (1797) (RIBA SB70/12, SB70/11, SB70/14). No confirmation has been found for a piggery or ice house at Thirkleby but Sir Thomas did have a vinery built in 1798. The expenses for that list carpentry, glass and the work of glazier, plumber, bricklayer, mason and blacksmith (LUSC/DD94, Box 2). It is most likely that the kitchen garden was built in the same phase of development, along with a ‘Managerie’ [sic], as both are listed in the 1815 survey and appear on the later tithe map (NYCRO ZPE; Figure 3).

Sir Thomas was clearly closely involved in the works, referring on 1796 to ‘my undertaking in building a house of some size, and laying out extensive grounds’ (LS JES/COR/15/1). The redesign of the parkland and gardens are associated with Adam Mickle II who was also employed at Newby Hall. He had been recommended to Sir Thomas by the Robinsons in January 1785 and was employed by him by the end of that month (BARC L30/15/54/250, 261; L30/14/333/308). There is little information on the changes he made but a slightly later description tells us ‘the verdant surface of the Park is graced with trees of venerable appearance, and clumps of well grown plantations’ (Neale & Moule 1820). The terms ‘venerable’ and ‘well grown’ implies some trees predating Sir Thomas’ improvements. He also mentions some ‘very old’ silver firs in a letter of 1818 (LS JES/COR/15/56). Another description notes ‘the grounds and gardens remodelled, partly from the proprietor’s own ideas, and partly from those of the late Mr Meikle. They contain some fine old common pine-trees (P sylv.) and a good kitchen garden’ (Loudon, 1826, p1079). The southern avenue survives as a feature, though the other two have disappeared by the time of the Greenwood map.

The ‘old wilderness’ including specimens of Quercus ilex/holm oak seems to have survived Mickle’s landscaping work:

‘We have just whip grafted “in the root” some Ilex on the common oak, having been unsuccessful of late in the common way - but have one plant about 14’ high, cleft grafted on common oak, which is of uncommon health. It was taken from some of the trees in the old wilderness now about 100 years old - which are so much more hardy than our native trees that an unmerciful thinning (by a landscape gardener in 1785) beech lime, sycamore + horse chestnut dies gradually - but the Ilex seems uninjured which is high encouragement for exertion in raising this charming tree.”(LS JES/COR/15/44).

There is little information about the pleasure gardens around the house. A letter of 1818 refers to cuttings of box and privet which perhaps were intended for formal parterres. Sir Thomas grew Glaucium fulvium (horned poppy) in 1811 and in 1818 planted Pyrus japonica ‘conspicuously from the windows, but cradled as I cannot trust the vermin hares + rabbits’(LS JES/COR/15/43 & 56).

That Sir Thomas was creating new plantations from the first is evidenced by a remark in a letter of 1798: ‘I gathered Viola canina this week in full blow in a young plantation’ (LS JES/COR/15/3). These may have been away from the main Park as there were 36 acres (14.5 hectares) of plantation ‘on the Moor’, along with a large pond, listed on the 1815 survey. The pond may be where Sir Thomas later planted Tupher (Typha) minima (dwarf bulrush) in 1812. Received from a Mr Brodie this was ‘packed in earth paper + matting; + sunk with a stone in a hard water stewpond secreted by plantation’ (LS JES/COR/15/44).

In 1812 Sir Thomas notes that Salix caprea (native goat willow) was abundant in the woods and ‘found holly natural layers’. He had the intention of layering some hundreds, presumably for his plantations (LS JES/COR/15/45). In 1818 he planted Rhododendron ponticum in the woods. Also ‘American bird cherry, Hippophae, Aucuba, Japonica + Juniper for experiment’ but these are destroyed by rabbits (LS JES/COR/15/56).

A comparison of the 1815 survey (NYCRO ZPE), albeit lacking its plan, with the later tithe apportionment of 1844 shows the remodelling of the estate was largely carried out by 1815, the total acreage rising by only by 12a 1r 33p (5.04 hectares). In 1815 about 153 acres (61 hectares) were parkland with clumps of woodland of which several areas can be equated exactly with Deer Park, Wheat Riggs and West park on the tithe map. The domestic core - the mansion and service buildings, menagerie, kitchen garden and orchard all have exactly the same areas given in both documents. The farm buildings and adjacent woodland are also the same in both documents. Oak Wood and Ruddings Wood are named in both; Ruddings remaining the same area, though the Oak Wood reduces in size by 7a 1r 12p which is exactly the area given in 1844 for ‘shrubberies at Hale’ (Figure 3), suggesting these were the same original area. If so the southern boundary of the shrubberies could have been established as part of the original landscaping. This boundary, probably a ha-ha, remained unchanged, appearing as an earthwork on the late nineteenth century map and as a stone revetted ditch in a later photograph (Ordnance Survey 25” map 1891; Robinson 2015, 176-77).

1815 - 1853

The only additions we can be certain that Sir Thomas carried out after 1815 were in 1817 when he built a mushroom house, based on the design of Isaac Oldacre, but ‘adapted what was necessary to existing buildings. In one respect I have no doubt but mine has the advantage for the flue is above ground’. In the same year he was planning a peach house ‘We have taken due pains in constructing my new house, which will be glazed this week.’ (LS JES/COR/15/54 & 55).

In the 1820s Sir Thomas’ son, Robert Frankland, started to show an interest in the gardens, perhaps under the influence of his wife. They seem to be embracing new fashions in planting similar to the gardenesque style advocated by Loudon. Sir Thomas writes ‘My son + daughter have been amusing themselves for some weeks in placing single trees + shrubs on the lawns - + so zealously that the Lady carries various articles + even digs’. They go to York ‘merely to ransack the Nursery Gardens’ (LS JES/COR/15/60 & 61). The following year they are ‘occupied with a little flower garden which they have made in the Wood.’ (LS JES/COR/15/65). In 1825 they have ‘beautiful plants of Chrysanthemum Indicum’ (LS JES/COR/15/74)

The tithe map of 1844 (Figure 3) shows the estate as it was during the tenure of Sir Thomas’ son Sir Robert Frankland Russell who is listed in the apportionment as holding a total acreage of 251a 1r 21p (101.73 hectares).

It is probable that he made any changes between inheriting the estate in 1831 and 1836 after which he was involved with improvements at Chequers. Extensions were made to the original house footprint to the northeast and the northwest which also appear on the 1st edition Ordnance Survey map a few years later (Figure 4). That to the northeast is probably the service wing visible in a later published photograph (Robinson 2015, 178).

By 1853, the terrace adjacent to the stable block has been altered, perhaps by Lady Louisa after her husband’s death. The small buildings had disappeared and there is a straight boundary abutting a further building at the south end. Also by 1853, another narrow rectangular building appeared between the stable block and the kitchen garden (Ordnance Survey 6” map 1856). The pleasure grounds to the east of the house had been extended, taking in part of the former East Park, and a fountain is shown in the grounds.

In the wider park by 1853, the distinct clumps of trees depicted in 1844, are less obvious. Lines of trees emphasise enclosure boundaries and to the south west of the Park a line of trees running southwest-northeast suggests a former boundary. The line of the old southern avenue is still clear, though possibly replanted, and shows parallel rows of conifers and deciduous trees. An Araucaria, Scotch Fir and Corsican Pine were planted in the pleasure grounds in 1842 by Sir Robert’s daughter, Augusta Louise, probably on the occasion of her marriage to Lord Walsingham. A commemorative plaque survives today.

In the kitchen garden, new greenhouses had been built in the centre of the area, along with the gardener’s house in the northwest corner and two glasshouses along the inside of the north wall replacing that on the tithe map.

Two mid-century descriptions of the park complement the map evidence:

(the hall).. is situated on the north west side of the village, on a gentle eminence, in an extensive and well-wooded park, commanding picturesque views of the romantic scenery around, and is approached through a magnificent ancient avenue of Scotch Firs, considered one of the finest in this part of the kingdom (Gill 1852, 337).

In 1859:

The park in front is of considerable extent, declining with easy slope to the east, the west, and the south, and adorned with a profusion of thriving timber. A fine avenue, composed chiefly of venerable firs, along which passed the carriageway to the old hall, yet forms a very interesting feature of the landscape (Grainge 1859,192-3).

During his lifetime Sir Robert clearly continued to be involved in the gardens at Thirkleby, gaining accolades for both floral and kitchen garden produce in the horticultural shows that were becoming popular. Among his gardeners, Mr Deuxberry, who was advertising oak timber in 1834 (Yorkshire Gazette 25 January 1834), may be the same one who worked at Moreby Hall. Robert Elliott employed at Thirkleby in 1841 is possibly the same as served as a judge at the North Riding Horticultural Show in 1839 (Yorkshire Gazette, 3 August 1839).

After Sir Robert’s death, Lady Frankland Russell continued to patronise horticultural shows. In 1850, she contributed ‘a splendid ‘flower of the Victoria Regia’ [Victoria Amazonica] to one of the stands at the Grand Floral and Horticultural Exhibition at Thirsk (The York Herald 10 August 1850, 3). This was most probably obtained from the Yorkshire Philosophical Society, of which Sir Robert had been a member. The Society had specimens supplied from Chatsworth in 1850 which continued to flourish for several years (Yorkshire Philosophical Society Annual Report 1850 10; pers. comm. Peter Hogarth). At the same event, Lady Frankland Russell’s gardener Mr Robertson was awarded an extra prize for three specimens of Euthrysa christigalli [?Erythrina crista-galli]. Robertson may be a misspelling of Robinson as a letter from Disraeli in 1850 states ‘Robinson, the gardener at Hampden, has gone as chief to Thirkleby. I believe he has 150£ pr. annm: besides house etc’ (Disraeli et al.1993, 359).

1855 - 1927

Further changes were made to the hall and gardens after the Payne Gallweys took up residence at Thirkleby in 1855 and before 1890/91 when the Ordnance Survey 25” map was surveyed (Figure 8; Ordnance Survey 25” map 1892). A new bay-fronted extension adjacent to the main entrance on the west side of the hall was added by 1894 (Figure 9).

In 1885 Lady Emily’s son, Sir Ralph Payne Gallwey had created a duck decoy, located in the plantations to the south west of the Park. Around the same time a lake surrounded by conifer plantation was created to the east of the pleasure gardens in the former East Park (Ordnance Survey 25” map 1892; Figure 8; Payne-Gallwey 1886 178). In addition to the pre-existing fountain two further fountains appear on the map, one close to the west end of the lake and another within the lake itself which had a Boat House on the southern bank.

A contemporary account tells us that ‘In the immediate vicinity of the hall are some fine specimens of the carnivorous [sic = coniferous] tree, the cedar of Lebanon, Wellingtonia Gigantea, and purple beeches’ (Bulmer 1890, 813).

In the wider park two ponds were created in separate enclosures along the southern boundary, not far from the Lodge gate. By 1910 these had become a single plantation called ‘The Wilderness’ (Ordnance Survey 25” map 1934). The former Home and Ruddings Woods were combined to form Home Wood and a new plantation, Pond Wood, with a series of circular ponds linked by water channels, created from two enclosures to the north of these. It is unclear which of these were referred to in 1894 when ‘Sir Ralph Payne Gallwey threw open the grounds attached to the hall and also the famed duck ponds with their varied collection of water fowl.’ (The Evening Press 8 August 1894, p3).

New lodges had been built at the southern end of the Avenue on the main road (A19) and also where the Avenue crossed into the Park itself. Two ‘Thirkleby lodges’ are listed in the census of 1871, probably the Wyatt lodge and the one near to the old Avenue. These are named ‘Park Lodge’ and ‘Avenue Lodge’ in 1881.

In the late 1880s Thirkleby started to host its own Horticultural Show. In 1890, ‘the gardens and grounds were in beautiful order, and were much admired’ and there was a ‘Display of stove & glasshouse plants supplied from Thirkleby Gardens’ (Yorkshire Herald 14 August 1890, 5). In 1891 ‘The grounds under the care of the head gardener, Mr Keepence, were in excellent order’ (The Yorkshire Herald 29 August 1891, 7).

Sir Ralph succeeded his mother in 1913 but the death of his only son in the First World War marked the start of the decline of the estate. After Sir Ralph’s death in 1916, his heir sold off outlying portions of the estate in 1919 (The Leeds Mercury 28 November 1919, 10; NYCRO ZKC Thirkleby) followed by further sales in 1925 including practically the whole of Great Thirkleby village (NYCRO ZKC; Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer 29 August1925, 7).

The Hall, Park and gardens in 1925 are described in this account:

An Adams house, it is built of white sparkling stone, smoothly dressed, and beautifully decorated. The design is Graeco Italian, and the south front is generally considered to be one of the best examples of this kind of architecture in England...Standing on an eminence, surrounded by a finely timbered park of 260 acres, the hall affords superb views of the Hambleton Hills and the Vales of Mowbray and York, while the western horizon is bounded by the distant hills of Whernside and Ingleborough. About the house are extensive lawns and flower gardens, and many rare pines, interspersed by winding paths, sheltered in the season by abundant foliage from sun and wind, together with fountains and ornamental lakes (The Yorkshire Post 24 October 1925, 13).

An undated album contains some photographs, taken most probably in the early 20th century, which give glimpses of the gardens (NYCRO ZPE). One shows the east lawn with the fountain and a number of small island beds of various shapes cut into the turf (Figure 10). This could predate or postdate another photograph from a different angle (Robinson 2015, 178) which shows the fountain but only one circular island bed. A photograph of the kitchen garden, apparently taken from the top of the wall, shows the layout unchanged from early times with four rectangular blocks planted with a variety of crops. There are a number of large trees in the centre and there is a line of smaller trees, perhaps fruit trees, along the path in the foreground, with a gardener working on them (Figure 11).

By 1927 Sir John Payne Gallwey had failed to sell or lease the property and took the decision to break up the fabric of the hall for auction:

Another great and historic Yorkshire mansion is doomed. This is Thirkleby hall, near Thirsk, long the ancestral home of the Franklands and the Payne Gallweys. It has been in the market for a long time, either with the park or a part of it, but apparently no one wanted it for personal occupation, and so it has been decided to break it up and sell the fabric piecemeal (The Yorkshire Post 19 February 1927, 14).

The architectural fabric, interior furnishings and fittings were auctioned off over three days (NYCRO ZKC). The outdoor effects auctioned on the third day included:

Handsome carved stone pedestal fountain representing two children carrying a fluted shell basin height approx 4’.

Ancient carved stone font.

Handsome carved stone flower vase and pedestal.

Decorative iron pedestal flower vase 2’4” high 2’basin.

Two rare old stone garden vases handsomely carved 22” high.

Iron fountain with the stone basin 15’ diameter. The iron fountain is probably the one in the photo of the east lawn (Figure 10).

Old stone pedestal and presentation sun dial 4’ high. This is probably the sun dial marked on the Ordnance Survey map (Figure 8).

Garden seats. Various garden seats are visible in Figure 12.

Old sun dial and the carved stone pedestal dated 1834 4’ high.

135’ iron fencing 4’6” high and gateway. Some of this is visible in Figure 12.

Stone built portico, paving around the mansion, balustrading, steps and pillars. The portico is probably that at the main entrance (Figure 9).

The hall was demolished, though the stables and the west lodge survived and these along with the site of the former Hall, lake and Home Wood had become a caravan park by the 1970s (Meridian Airmaps 1972; Ordnance Survey Plan 1978).

Location

Thirkleby Park lies to the west of the village of Great Thirkleby within the pre 1832 parish of that name and the modern parish of Thirkleby High and Low with Osgodby. It is about 4.5 km (2.8 miles) south of Thirsk, just to the east of the A19 and bordering Low Lane which runs from the A19 towards Carlton Husthwaite.

Area

The extent of the designed landscape is approximately 95 hectares (235 acres)

Boundaries

The Park is bounded by Low Lane to the south and the approach road to the village on the east. To the north and west the Park is bounded by farmland. An additional strip of land to the south of Low Lane marks the original Avenue

Landform

The core of the estate lies at c. 65 m AOD and slopes down to c.40 m AOD to the south and east. The valley of the Thirkleby Beck lies to the east of the village, draining to the south where other small watercourses drain westwards across low lying land to join the Cod Beck. The bedrock geology is sedimentary, Jurassic mudstone overlain largely by Vale of York formation clay with a narrow band of Breighton Sand formation along Low Lane. Soils are slightly acid but base-rich loamy and clayey soil supporting grassland and arable with some woodland.

Setting

The site of the 18th century hall and domestic buildings is situated at c. 65 m AOD on higher ground, sheltered by plantations to the north and with open views to the south, west and east. The Park slopes southeastwards towards Great Thirkleby village about 0.5 km away. The site is within the National Character Area 24 Vale of Mowbray.

Entrances and approaches

Thirsk Lodge/Park Lodge: Grade II (NHLE: 1151340 NGR: SE 461 789) and drive.

The main approach to Thirkleby Hall and Park as designed in the late eighteenth century. Attributed to James Wyatt, the architect of the Hall. It still exists today. (Figure 6; Tithe map Thirkleby - IR 30/42/367 1844).

The Avenue

Lodge on Low Lane

This was built sometime between 1853 and 1890 and might be that listed on censuses as Avenue Lodge in 1881. It still exists today (Ordnance Survey 25” map 1892).

Lodge on A19 near Thirkleby Bridge

Marked as a lodge, this was built by 1890 and might be that listed on censuses as Avenue Lodge in 1881. It exists today (Ordnance Survey 25” map 1892).

Principal buildings

Old Thirkleby Hall (demolished)

The earlier hall, probably built in the seventeenth century, if not earlier, stood near the church and close to the end of the village street. It was approximately 97’ x 70’ (30 x 21 metres) in size (Figure 1, Figure 2).

Thirkleby Hall (demolished)

The hall built by Sir Thomas Frankland, from designs by Wyatt, was completed between 1785 and 1792. A depiction of 1820 shows a two storey seven bay south facing frontage with steps leading to an entrance flanked by full height Corinthian columns. On the east side a central bay extends to the full height of the building. A later photograph from a similar angle (http://www.lostheritage.org.uk/houses/lh_yorkshire_thirklebypark_info_gallery.html accessed 4 January 2020) shows these facades to have remained unchanged into modern times. However, additions were made to the north side of the house sometime before 1844 and further alterations were made to the west front 1890-1894. The hall was demolished in 1927 (Tithe map Thirkleby - IR 30/42/367 1844; Ordnance Survey 6” map 1856; Figure 7)

Stables Grade II (NHLE: 1150701 NGR: SE 470 791)

The stable block immediately to the north of Thirkleby Hall is also by Wyatt and built at the same time as the Hall (Figure 5).

Gardens and pleasure grounds

The earlier hall had three ‘Long Walks’ radiating out from the house. Parterres bordered by yew columns surrounded the house and these may possibly have contained statuary. In the early eighteenth century a wilderness was created, though its position is unknown.

After the new hall was built and the park remodelled, the main pleasure grounds lay immediately to the west, south and east of the house. An area of shrubberies was bounded at the southern edge by a possible ha-ha. The Home Farm to the east lay at the end of a further belt of woodland (Figure 3). A terraced area lay to the east of the house and stables.

Between 1844 and 1853 the pleasure grounds to the east of the house were extended. Open lawns, with a fountain, were studded with trees and threaded by paths. It is likely that there were island beds with shrubs and flowers as noted in Sir Thomas Frankland’s letters. The accounts of local horticultural shows give evidence that the flowers grown included dahlias, fuchsia, hollyhocks, roses and pansies. A large number of pansy varieties were grown: Trafalgar, Mrs Harcourt, Northern Star, Lady Constable, Voltigeur, Hall’s Rainbow, Duchess of Rutland, Major, Conquering hero, Tryphosa, Berryer, Telegraph, Flying Dutchman, Juventa, Patho, California, Constellation, Over Newton, Excellent, Supreme, Helen, Duke of Norfolk, Sir W Herschel (Yorkshire Gazette 28 June 1851, 6).

A further extension of the pleasure gardens to the east was added before 1885 when the lake surrounded by coniferous plantation and two more fountains were created (Figure 8; Ordnance Survey 25” map 1892). A sundial is shown to the south of the south facade in 1892.

Kitchen garden

There were orchards associated with the old hall and presumably a kitchen garden as well, though their position is not known. These probably corresponded to enclosures seen on the LIDAR image (Figure 1). Pears may have been grown in the orchards as Sir William Frankland’s father-in-law Lord Fauconberg wrote a letter in 1681, encouraging him to plant pears at Thirkleby: ‘This pains I take only to make you as good a gardener as myself’ (RCHM 1900, 47).

The walled kitchen garden (c. 118m x 58m) built by the 6th Baronet lay immediately to the north of the stables. The walls are largely built of bricks around 2” thick with surviving nails in the walls for training trees. The interior was divided into four segments by paths with a slightly off-centre dipping pond. A slip garden enclosed the east and part of the south boundaries of the main garden. The tithe map of 1844 shows a building in the north east corner, most likely a greenhouse, against the internal wall with a possible service building placed centrally on the outside of the north wall. A gap in the surviving wall today shows it to be hollow with flues to aid circulation of warm air (Tithe map Thirkleby - IR 30/42/367 1844). By 1853 this glasshouse had been replaced by others placed centrally along the north wall and in the centre of the area. A gardener’s house was built in the north west corner (Ordnance Survey 6” map 1856; 25” map 1892). To the west of the walled garden, there was an area of orchard c. 60m square. The walled garden can be seen in a photograph of the early 20th century (Figure 11). The walled enclosure and some of the later service buildings behind the north wall survive today.

The letters of the 6th Bt to James Smith of the Linnean Society (LS) give copious detail on what was grown here in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Fruit trees, pears (d’Auch), apricots (Moor Park), peaches (Gros mignon, Noblesse, Galende, Buckingham mignon), nectarines, cherries and mulberries were grown on open walls and borders as well as under glass or in pots. Figs were tried in the vinery but found ‘not worth their room’. Fruit trees on open walls were protected by oiled paper frames ‘We have had a profusion of peaches + nectarines so as to give away 4 or 5 dozen per day for many days together chiefly from the intermediate crop, secured by oiled paper frames in the spring’ (LS JES/COR/15/71, 26 September 1822).

Apple varieties grown included Downton Pippin, Golden Harvey, Grange, Foxley crab, Newtown pippin, Siberian crab (espalier), Ribston Pippin, Carlisle codlings, Hawthorn Dean, Keswick codlings and probably the Rymer apple which Sir Thomas Frankland was credited for bringing to the notice of the Horticultural Society (Trans. Hort. Soc. 1822. 4:107).

In the vinery Verdelho, Frontiniac [Frontenac], Lombardy, Black Prince, Frankendale and muscadines were grown. Sir Thomas also grew melons in frames, adopting ‘Mr Knight’s form of frames’ which he illustrates in a letter (LS JES/COR/15/47). His melons included the orange Canteloupe, the Great Mogul (‘a worse kind I never saw...’), and his favourite Green Egyptian for which he won the Horticutural Society’s Banksian Medal in 1820 (Trans. Hort. Soc. 1822, 4:514). A descendant of this melon, referred to in 1901 as ‘Thirkleby Park’, was grown at Merton Park the seat of Lord Walsingham, a family connection by marriage (JRHS 1901, clxxxvii).

Soft fruit was also grown: raspberries (White Antwerp) and strawberries (Pine, Hautbois, alpine, red chili and black). He patronised the nursery of James Lee in Hammersmith for soft fruit and vine plants and spent £2 10s 6d on an order in October 1818 (/DD94 Box5-6).

His vegetables included kale, ‘We have been successful in kale for forcing of which I got pots made with covers’ (LS JES/COR/15/41). He also grew pease, cucumbers and asparagus ‘raised in one of the pigeon holed frames invented by Mc Phail’ and ready in abundance in December 1820 (LS JES/COR/15/60 & 61). Onions, garlic and shallots were also grown. One of his gardeners, Mr Elias Hildyard, had a remedy for attack by grubs which is mentioned in the Horticultural Society Transactions/Gardeners Magazine (Loudon 1828 174-5).

A keen botanist Sir Thomas exchanged seeds with various correspondents and must have used the glasshouses to raise plants. In letters of 1818-20 he mentions Arauceria imbricata [monkey puzzle], Poinciana pulcherrima (Gul Mohr), Ipomoea quamoclit, Annona squamosa, Abrus precatorius and Adenanthera pavonina and air plants - Epidendrum cochleatum [Prosthechea or clamshell orchid?] and Tillandsia (LS JES/COR/15/57, 58 & 59). Hyacinths (Groot Vorst) were grown in the house (Trans. Hort. Soc. 1822, 4 :130).

In the 1840s and 1850s the prizes won at local horticultural shows reveal what was grown in the walled kitchen garden. Fruit included strawberries, red and white currants, red and white raspberries, pears, grapes, peaches and cherries. Cucumbers, peas, cauliflowers, celery and parsnips won prizes for vegetables. (Yorkshire gazette 22 April 1843; & Supplement 4 July 1848; The York Herald 10 August 1850; 20 September 1851, 6).

In the 1890s Thirkleby had its own Horticultural show, winning further prizes including for tomatoes which became more popular in the nineteenth century (The Yorkshire Herald 29 August 1891). At the Thirkleby Show of 1894 there was a ‘Grand display of hothouse and greenhouse plants which were supplied from the hall, the head gardener, Mr Kupence [=Keepence], being highly successful as an exhibitor’ (The Evening Press 8 August 1894). Mr S Keepence was still gardener at Thirkleby in 1903 and 1904 and reported on the performance of fruit crops for the Gardener’s Chronicle. Apples, pears, plums, cherries, peaches & nectarines, apricots, small fruits, strawberries were being grown, though 1903 was not a very good year (Gardener’s Chronicle 1903 August 1, p73; Gardener’s Chronicle 1904 July 30, p71).

Park and plantations

The early Park

The early park, apparently bounded by a wall, is shown on Jeffery's map of 1771 (Figure 2). Three avenues or Long Walks extend to the north, south and east of the house and church which stand on the east side near the village. There is a clear entrance gap in the Park perimeter on the west side and the western avenue extends beyond the park boundary as far as the junction of A19 and Bagby Road. The avenue to the south also extends beyond the Park boundary and across Low Lane towards the modern A19. This survives today and is marked by a minor road and the remnants of an avenue. A shorter avenue is shown leading northwards as far as the park boundary.

The eighteenth century Park

The extent of the park in the late eighteenth century is broadly the same as that on Jeffery's with the addition of the area, lying within the parish of Bagby, which carried the main entrance drive leading from Thirsk Lodge. On the east side the small area of the earlier park which was bordered by Mill Lane did not form part of the later park. Parkland extended to the east south and west of the Hall, stables and kitchen gardens and was divided into a number of enclosures - West, East and South Parks closer to the house, and Wheat Riggs, Church Field and Deer Park beyond alongside Low Lane. Two semicircular tree clumps lay along the eastern border of East Park and clumps of trees were scattered across other areas of the Park, more clearly delineated on the tithe map than on the 1st edition Ordnance Survey map (Tithe map Thirkleby - IR 30/42/367 1844; Ordnance Survey 6” map 1856 Figures 3 & 4).

The eighteenth century plantations

The domestic buildings were sheltered to the north by Ruddings Wood, Oak Wood and The Stripe, a long plantation bordering the entrance drive and forming the northern boundary of the estate. Oak Wood and Ruddings Wood are not shown on Jeffery's map and are not characterised as ancient woodland. It is probable therefore that these were newly planted as part of the remodelling of the estate.

Ruddings and Oak Woods were threaded with paths linking the area near the kitchen gardens, the pleasure grounds and the shrubberies and woodland which extended south eastwards towards the Home Farm (Ordnance Survey 6” map 1856, Figures 3 & 4).

Later plantations

In the late nineteenth century a coniferous plantation was created around the lake to the east of the original pleasure grounds. Also a further plantation, the Wilderness, was developed around the ponds alongside the southwestern boundary of the Park near Thirsk Lodge. Pond Wood was created to the north of Oak and Ruddings Woods, though this was not linked by paths to the woodland or pleasure grounds (Ordnance Survey 25” map 1892; Ordnance Survey 25” map 1934).

Plantations outside the Park

There were other plantations, not forming part of the park, to the west of the A19. The plantations ‘on the Moor’ listed on the 1815 survey corresponded to Near Moor, Middle Moor, Far Moor and Pond plantations on the tithe map (Tithe apportionment Thirkleby 108, 112, 117, 118).

Water

It is unknown if there were water features associated with the early hall, though the LIDAR image suggests some water-filled boundaries which by the time of the tithe map were reduced to one small subrectangular pond. This had gone by 1853. The redesign of the park in the late eighteenth century did not include water features.

The Lake which exists today was added to the garden in 1885. It is c.100m long with two islands and a fountain at the west end. A Boat House (now gone) was located on the southern edge and a path circumnavigated the shore linking with the those in the pleasure grounds (Ordnance Survey 25” map 1892).

Two ponds were created along the southern boundary of the park near Thirsk Lodge by 1890, later surrounded by plantation (Ordnance Survey 25” map 1934).

Sometime before 1890 a series of linked circular ponds were created in a new plantation in two fields to the north of Oak and Ruddings Wood. These possibly might have been associated with the raising of wildfowl (Ordnance Survey 25” map 1892).

Away from the park itself, Sir Ralph Payne Gallwey made a duck decoy in 1885 in the plantations to the south of the A19.

Books and articles

Atkinson, J.C. 1886. Quarter Sessions Records. The North Riding Record Society Vol 4.

Brown, W. 1897. Yorkshire lay Subsidy (1301). Yorkshire Archaeological Society Record Series 21.

Brown, W. ed. 1909. Yorkshire Star Chamber Proceedings Yorkshire Archaeological Society Record Series Vol 41.

Bulmer, T. 1890 History, topography and directory of North Yorkshire. Preston T. Bulmer and Co, 813.

Clay, John William 1899. Dugdale's Visitation of Yorkshire, with additions. Vol 2. Exeter, W. Pollard & Co 243-248.

Cousins, M. 2011. ‘Ditchley Park – A follower of Fashion’, Garden History 39, 2: 143-179.

Disraeli, B., Conacher, J. B., Matthews, J., Wilson Gunn, J.A., Wiebe, M.G. 1993. Benjamin Disraeli Letters: 1848-1851 Vol 5. University of Toronto Press.

Downes K. 1953. ‘Hawksmoor’s sale catalogue’, The Burlington Magazine 95, 607: 332-335.

Gill, T. 1852. Vallis Eboracensis: Comprising the History and Antiquities of Easingwold and its Neighbourhood. London, Simpkin, Marshall & Co.

Grainge, W., Baker, J.G.,1859. The Vale of Mowbray: a historical and topographical account of Thirsk and its neighbourhood. London, Simpkin, Marshall & Co.

Harvey, J.H. 1974. Early Nurserymen. London, Phillimore & Co Ltd.

Loudon, J.C. 1828. The Gardener's Magazine and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement, 3 London, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green.

Macky, J. 1722. A Journey Through England: In Familiar Letters. Vol 1 & 2. London

Neale, J. P., Moule, T. 1822. Views of the seats of noblemen and gentlemen, in England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland Vol 5. London, Sherwood, Neely, and Jones.

Payne-Gallwey, R. 1886. The book of duck decoys, their construction, management, and history. London, J. Van Voorst.

RCHM 1900. Report on the manuscripts of Mrs. Franklin-Russell-Astley, of Chequers Court, Bucks. Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts.

Robinson, J.M. 2015. Felling the Ancient Oaks. London, Aurum Press 174-179.

Gardeners' Chronicle: a weekly illustrated journal of horticulture and allied subject. Series 3: Vol 36 1904. Vol 34 1903. Vol 20 1896. London.

Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society (JRHS). Vol XXV, 1900-1901. London.

Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London (Trans. Hort. Soc.). Vol 4, 1822.

YPS: Yorkshire Philosophical Society Annual Report 1850

Newspapers

The Evening Press 1893, 1894

Yorkshire Gazette 1834, 1839, 1851, 1892

The York Herald 1850, 1851, 1890

The Yorkshire Herald 1891

The Yorkshire Post 1912, 1925

Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer 1925

Primary sources

Bedfordshire Archives & Records Service (BARC)

Wrest Park Manuscripts

L 30/15/54 Correspondence between Thomas Robinson (1738-1786) 2nd Baron Grantham and his brother Frederick [Fritz]

Centre for Buckinghamshire Studies (CBS)

D-X1069/1/2 Diary of John Baker of Cornhill, linen draper, while travelling from Tring, Hertfordshire, to Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire, 25 May-13 July 1728

Leeds University Special Collections (LUSC) Yorkshire Archaeological Society archive

DD94 Payne Gallwey papers

Linnean Society (LS)

JES/COR/15/1-75 Correspondence of Sir James Edward Smith (1759-1828) Letters from Sir Thomas Frankland

The National Archives (TNA)

Tithe map Thirkleby - IR 30/42/367, 1842-44

Tithe apportionment Wighill - IR 29/42/367, 1842-44

North Yorkshire County Record Office (NYCRO)

ZPN Frankland of Thirkleby family papers

ZPE Frankland-Payne-Gallwey of Thirkleby (2nd deposit uncatalogued papers).

Survey and Valuation of Estates belonging to Sir Thomas Frankland Bart. 1815.

Photograph album

ZKC Sale catalogue for Thirkleby Hall 1927

Z114 Frankland Rentals and accounts

ZT Turton of Upsall family papers

Upsall Castle letter books of Dr John Turton Letters from John Reed (steward)

Royal Institute of British Architects Special Collections (RIBA)

SB72/8(1-27), SB96/9(28-48) Working drawings for Thirkleby Park, Thirsk, North Yorkshire, for Sir Thomas Frankland Bart, by James Wyatt

Maps

Ordnance Survey 6” map, surveyed 1853, published 1856.

Ordnance Survey 25” inch map Yorkshire CIV.1, surveyed 1891, published 1892.

Ordnance Survey 25” inch map Yorkshire CIV.5, surveyed 1890, published 1892.

Ordnance Survey 25” inch map Yorkshire CIV.1, revised 1910, published 1934

Ordnance Survey 25” inch map Yorkshire CIV.5, revised 1910, published 1911.

Ordnance Survey Plan 1:2500 1978

Meridian Airmaps 59/72/212, flown 13 July1972

Jeffery's map of Yorkshire, c. 1771

Speed’s map of Yorkshire: North and East Riding 1610

Blaeu map of Yorkshire, 1645

Warburton Map of Yorkshire, c. 1720

Greenwood Map (surveyed 1817 & 1818 and corrected 1834)

Figure 1 - LIDAR image and interpretation, showing the site of the old hall (as mapped by the Ordnance Survey) at the end of the extension to the village street. (image from https://houseprices.io/lab/lidar/map using Environment Agency data released under an Open Government Licence).

Figure 2 - Extract from Jeffery's Map of 1771. Reproduced by permission of the North Yorkshire County Record Office (Jeffery's Plate 8).

Figure 3 - Extract from Thirkleby Tithe Map, showing the Park with names from apportionment and rotated to align with the National Grid (National Archives IR 30/42/367).

Figure 4 - Ordnance Survey 6” map, surveyed 1853, published 1856, with inset of main area. Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Figure 5 - View of the stables at Thirkleby Hall from the west, taken in the early 20th century. Reproduced by permission of the North Yorkshire County Record Office (NYCRO ZPE).

Figure 6 - View of the west lodge to Thirkleby Park today. The roughcast extensions at each side are modern (M. Mathews).

Figure 7 - Thirkleby Hall seen from the south in the early 19th century, as published in Neale & Moule, 1822.

Figure 8 - Ordnance Survey 25” inch map Yorkshire CIV.1, surveyed 1891, published 1892. Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Figure 9 - View of the main west entrance of Thirkleby Hall from the 1927 sales catalogue. Reproduced by permission of the North Yorkshire County Record Office (NYCRO ZKC).

Figure 10 - View of the lawns to the east of Thirkleby Hall taken in the early 20th century. Reproduced by permission of the North Yorkshire County Record Office (NYCRO ZPE).

Figure 11 - View of the walled kitchen garden at Thirkleby Hall from the top of the wall at the south west corner, taken in the early 20th century. Reproduced by permission of the North Yorkshire County Record Office (NYCRO ZPE).

Figure 12 - View of the south facade of Thirkleby Hall from the 1927 sales catalogue. Reproduced by permission of the North Yorkshire County Record Office (NYCRO ZKC).