The designed landscape around the present Hawksworth Hall, which was built during the early 17th century, has been evolving with the changing fashions and successive owners since that time. The landscape that is seen today was largely developed over the period 1768-1786 by Walter Ramsden Beaumont Hawksworth [later Fawkes] (1746-1792) who consulted two landscape designers. The first was probably Anthony Sparrow and the second Thomas White. Though neither designers’ scheme was fully implemented, elements were used that included a redevelopment of an entrance carriageway to the hall, installation of a ha-ha and creation of vistas across the park and relocating the walled kitchen garden from a central position within the park to a peripheral corner. The gardens and park then remained largely unchanged when the hall ceased to be the primary residence of the Hawksworth family in 1786 until the early 20th century when the park was developed into a golf course. Today the historic designed landscape around Hawksworth Hall remains largely legible and extant.

Estate owners

The village of Hawksworth was once within the ancient parish of Otley and part of the feudal estate of the Archbishop of York and from at least the 9th century functioned as a source of income for the Church. By the 14th century the Archbishop had granted the Hawksworth portion of his estate to the Warde family who served as the mesne lords (Laurence 1991, 2).

The Hawksworth family were Scandinavian by origin and are known to have been living in the area since at least the 12th century. Two individuals bearing old Norse names, Toki and Thurstan, are documented in 12th century records of the area. Recordings of the surname Hawksworth occur in early 13th century deeds relating to Lenard de Hawksworth, son of Toki and of Thurstan’s sons William and Hugh de Hawksworth. The branch of the family that had their seat at Hawksworth Hall descended from Robert de Hawksworth, who was living in the area in 1227, and his son Walter would be the first to bear a Christian name that would be retained by successive generations (Laurence 1991, 14).

One Walter de Hawksworth married Beatrice Warde in the mid-13th century, and it was through this marriage that the Hawksworth family attained manorial rights and the Hawksworth estate in a deed dated 1273. As there is limited reference to the family in archive material for the next 150 years, Laurence (1991, 16) speculated that their principal residence may have moved to their other estate, Mitton in Lancashire. The earliest known reference to a manor house at Hawksworth dates from 1440 when Thomas Hawksworth living in York leased the estate and mansion to his son, John.

The history of the present-day hall started with Walter I (1538-1620) and Isabel Hawksworth. He was succeeded by his son Richard (d. 1657) who received a knighthood in his twenties, but at the outbreak of civil war pledged an allegiance to the Parliamentarians. Soon after he was arrested and gaoled at York for almost 2 years.

On Richard’s death, his only son Walter II (1625-1677) acquired Hawksworth followed by his young son, another Walter III (1660-1683) who inherited at the age of 17-years-old but died only six years later of consumption. During his short life, Walter III was created a baronet by Charles II. His only surviving child, the 5-year-old Walter IV (1678-1735) inherited the estate and became the 2nd Baronet. Dying without a direct male heir at the age of 57 years (Walter IV and his wife Judith had two surviving daughters the eldest being Frances), the estate passed to a grandson.

Walter V Ramsden (c. 1722-1760), the son of Frances Hawksworth and Thomas Ramsden of Crowstone, inherited Hawksworth at the age of c. 13 years on the death of his grandfather Walter IV the 2nd Baronet in 1735. He took the name Hawksworth, but the baronetcy became extinct. Unfortunately, Walter V Ramsden [Hawksworth] died young, in his thirties. With his wife Frances (d. 1755) having died 5 years previous, their 14-year-old son, another Walter VI (1746-1792), was left an orphan. Ayscough Fawkes of Farnley Hall, Otley (approx. 6 miles from Hawksworth), who was distant relative of the Hawksworth family through marriage, was appointed a trustee and guardian of the young Walter VI Ramsden Beaumont Hawksworth.

In 1786, Walter VI inherited Farnley Hall and made it his principal residence and assumed the name Fawkes, as required of the legacy, with Hawksworth being subsumed into the Fawkes estates. On the death of Walter VI Ramsden Beaumont Hawkesworth [Fawkes], Hawksworth passed to his son and member of parliament for Yorkshire, Walter Ramsden Fawkes (1769-1825). Hawksworth Hall was retained by the family until Frederick Hawkesworth Fawkes sold the entire estate in 1919 (Laurence 1991, 99; Richardson 1991, 21).

From 1786 until 1919, the hall was occupied by a series of tenants. The most notable of these, with respect to the gardens, were Timothy Horsfall (a wealthy merchant and local magistrate from Bingley) 1830-1877 and Duncan G. Law (the last tenant and subsequent owner of the hall) who resided there from 1899 until his death in 1923 (Speight 1905, 296; Laurence 1991, 31). Edgar L. Gaunt, a textile manufacturer, occupied Hawksworth as his private residence from 1923-1955 when it was sold to the Bradford and District Spastics Society (later known as Scope). It became a specialist residential school for children with disabilities until it closed in 1999 (Laurence 1991, 31). The hall was then, briefly, held by a company that manufactured stairlifts before returning to a private residential home c. 2000, which it remains to this day.

Key owners and tenants responsible for major developments of the designed landscape and dates of their involvement:

Walter I and Isabel Hawksworth (pre-1611 – 1620)

Walter II Hawksworth (1657 – 1677)

Walter IV Hawksworth, 2nd Baronet (1699 – 1735)

Walter VI Ramsden Beaumont Hawksworth [later Fawkes] (1767 - 1786?)

Timothy Horsfall (1830 - 1877)

Duncan Law (1899 - 1923)

Early history of the site

The earliest parts of the present Hawksworth Hall were built in the early 17th century by Walter I (1538-1620) and Isabel Hawksworth (Figures 1 and 2). Ornate plaster work within the first floor Great Chamber (also known as King’s Chamber) displays their coat of arms and the date 1611 stand testament to their work (LUSC YAS/MS1961).

Walter II (1625-1677) inherited Hawksworth at the age of 32 years and immediately started major alterations greatly enlarging the hall during the decade 1660-1670. A large barn was built to the rear (1661), the eastern half of the hall was added (1664) and stained glass commissioned (1666) (Laurence 1991, 21). Hearth Tax records from 1672 identify a substantial hall boasting 17 hearths (Hearth Tax Digital). As far as is known, Hawksworth Hall was not enclosed and did not have a deer park at this time as none are shown on the Blaeu map of 1662-5.

Walter III (1660-1683) the 1st Baronet died young, leaving Hawksworth to his young son Walter IV (1678-1735). It is during the time of the 2nd Baronet that there is the first recorded comment on the gardens. Ralph Thoresby, antiquarian and diarist of Leeds, recorded on the 31st August 1702:

‘we came to Hawksworth, where we dined with the ingenious Sir Walter Hawksworth, who is making pleasant alterations and additions to that ancient seat and gardens’ (Hunter 1830, 383).

Thoresby may have been delighted by terracing to the south and east of the hall shown in a drawing made by Samuel Buck c. 1720 (Wakefield Historical Publications 1979, 204-5). Buck’s sketch shows a balustraded terrace across the south front of the hall with steps to a path dividing an enclosed front garden and leading to a gate with ornate gate piers, further steps, and adjacent low wall with railings. To the east of the hall there is a second enclosed garden with three or four visible terraces and planting that may include topiarised cones. Railings (or a claire voie) are apparent on the east side of the enclosed garden that would have allowed views to the old walled kitchen garden and park (see below). This non-axial arrangement would have been dictated largely by the steeply sloping site on which the hall was built.

In February 1729, Walter IV purchased 3000 quickwoods (usually hawthorn or whitethorn) at a cost of 14s 6d (TS SD17). Together with other payments made during January and February, the recorded expenditure suggests that in the region of 10,000-15,000 quickwoods were planted over the two-month period of February and March. Some are specifically referred to as being planted within the ‘wood’ (TS SD17), but it may be that some were used at boundaries or around more valuable trees that were being planted, possibly those forming the avenues that are indicated on the 1768 survey. Payments were also made during the year for hedge cutting, ‘stubbing’ (removal of trees), to ‘Chip the gardner’ on several occasions, and one bill in March/April paid a gardener from Leeds 14s 3d. Whether this payment was for further quickwoods or other plants and seeds is unclear. Finally, in October 1729 a man was paid 4s 0d to value the wood. Though archival evidence is lacking, it is likely an area of wood was subsequently felled and the timber sold. It remains clear that sizable works were being undertaken in the grounds at this time (TS SD17).

Walter V Ramsden (c. 1722-1760) inherited Hawksworth on the death of his grandfather the 2nd Baronet in 1735 and took the name Hawksworth. Nothing is known of this Walter’s gardens beyond a ‘new spade for the garden’ having been purchased from the blacksmith in 1758 for 3s 8d (LUSC YAS/DD/146 Box 28).

Chronological history of the designed landscape

1767 – 1786

Walter VI Ramsden Beaumont Hawksworth (1746-1792), having been orphaned at the age of 14 years, was placed under the guardianship of the Fawkes of Farnley Hall, Otley. On attaining his majority in 1767 he quickly initiated a period of landscape improvements at Hawksworth Hall.

In 1764 aged 18 years, Walter VI matriculated from University College, Oxford (Robertshaw 1976, 260). Two years later, also whilst at Oxford, Walter VI purchased several art works from the dealer A. Campione. Amongst these were two unspecified ‘lansdskips’ [sic], and etchings by Della Bella, Salvator Rosa and Claude Lorrain at a cost of £3 12s 0d (LUSC YAS/DD/146 Box 28). Clearly the young 20-year-old Walter VI was interested in landscapes, and these may have subsequently influenced his designs for the gardens at Hawksworth. He would certainly have been very familiar with the gardens of his guardian and later benefactor at Farnley Hall. Buck’s sketch c. 1720, illustrates enclosed walled gardens on three sides of Farnley Hall with a garden pavilion within the corner of one section (Wakefield Historical Publications 1979, 200-1). By 1771, the high walls had been removed, but the pavilion was retained (Tupholme 2015, 11).

Expenses show that throughout December 1767, Walter VI travelled to a number of other estates, including Harewood (LUSC YAS/DD146 Box 28). Being a frequent visitor to Harewood, it is likely that Walter VI would have been influenced by the fashionable improvements being undertaken by his friend, Edwin Lascelles. Lascelles had recently built the elegant Harewood House (1754-1801), designed by John Carr (Warleigh-Lack 2013, 294), and had commissioned plans from Lancelot Brown (1758), Richard Woods (c. 1764) and Thomas White (1765) for the landscaping of the grounds (Turnbull and Wickham 2022, 22-23). Soon after taking responsibility for Hawksworth, Walter VI commissioned surveys and plans of his estate from the landscape designers Anthony Sparrow and Thomas White. Anthony Sparrow was the foreman to Richard Woods (early 1760s-1765) and later Thomas White (from 1765 and at least intermittently until 1774) whilst working for Lascelles at Harewood House (Finch, 2020; Turnbull and Wickham 2022, 37). It is possible that Lascelles introduced Walter VI to these designers.

The survey by Sparrow (1768) (LUSC YAS/DD/193/8) shows the hall and gardens separated from the park by the public highway that links the village of Hawksworth to the west with the town of Guiseley to the east (Figure 3). To the rear of the hall there are three unspecified outbuildings. Though lacking detail there is the suggestion of an entrance courtyard on the west side of the hall, garden to the front and an enclosed garden with a terrace to the east, the latter two features correspond with those illustrated by Buck c. 1720. Two tree-lined avenues run east-west; the upper avenue also displays a distinctive circular copse of trees. Trees envelop the hall to the north and west. Across the public highway, the park is divided by a wall running north-south and a walled-garden abuts this wall. The park is relatively devoid of features beyond a public footpath (extant), two wooded areas, a few clumps of trees (one with an outbuilding of unknown function) and an area of trees shown in a grid, probably depicting an orchard.

In the same year that Sparrow surveyed Hawksworth, archival material indicates that alterations to the estate were already being undertaken (LUSC YAS/DD/146 Box 28). Most notable amongst the expenses in the archive are those relating to work on the ha-ha at the front of the hall with men being paid to ‘rake the earth lower and casting the earth back from the wall’ and ‘casting more earth ought [sic] of the ha-ha near the front of the hall’. Whilst working on the ha-ha, John Nevil was paid for walling in the adjacent kitchen garden. It is at this time that the extant walled garden replaced the ‘Old [walled kitchen] Garden’ shown in Sparrow’s survey. Other structural alterations included the removal of ‘the garden house’ (location unknown) which engaged William Mawson in three days of work. Tree and hedge planting including 130 firs ‘50 largest raised firs…80 more D[it]to [smaller] at 1d per’ and 20 larches were purchased from Joseph Balfour. Also, ‘quickwoods’ whitethorn hedging was purchased, and garden seed procured from Perfect’s Nursery, Pontefract. John Deane was regularly paid throughout 1768 for ‘work in the garden’ with assistance from Kitson (LUSC YAS/DD/146 Box 28). Although nothing is known of John, the Deanes were an established farming family in the village.

In 1769, two landscaping proposals for Hawksworth were submitted. One, although unsigned, is believed to be in the hand of Sparrow (Turnbull and Wickham 2022, 201) and a second is by Thomas White (LUSC YAS/DD193/9) (Figure 4). Given that these plans are dated the year after archive material suggests that improvements to the gardens had begun, it does mean that Walter VI had been consulting with designers for some time.

There are similarities between the two designs. Both offer an ambitious proposal to reroute the public highway away from the front of the hall onto the hill above, running behind the hall and then dropping back down into the village west of the property. This would have been difficult to achieve requiring an Act of Parliament and does not appear to have been attempted. Other similarities include the removal of the enclosed rectangular garden to the front of the hall, the relocation of the wall garden to an area in the west of the park (that almost corresponds to the extant walled garden), and landscaping of the parkland with clumps and specimen trees. In other respects, the two proposals differ markedly.

The suggested improvements attributed to Sparrow see the upper tree-lined avenue retained, indeed a section carries part of the rerouted road, which then continues into open park planted with a line of clumps of trees to the north. Vestiges of the lower avenue create an informal approach to the rear of the hall. Perhaps the most interesting part of the design is in the area close to the hall where elliptical planting areas flank the east and south-west sides of the hall. A sweeping carriageway runs roughly east-west whilst a curving ha-ha offers unobstructed views across the park.

In contrast, White suggested removing the avenues and extending the pleasure ground both to the north of the hall (into an area was noted as ‘plow’d ground’ in Sparrow’s design) and east in a meadow known as Guiseley Seat (as named on the 1848 tithe map) (Figure 4). Surprisingly this new area to the north is enclosed on all sides with a belt of trees with no apparent vistas extending beyond the pleasure ground, despite there being spectacular views across the valley. To the southwest of the hall, a band of trees conceals the new walled garden and adjacent farmland, but otherwise the park remains largely open with few planted clumps and specimen trees with unobstructed views across a carefully positioned ha-ha.

Neither of these designs were implemented as proposed. Nor, unfortunately, have recorded payments to Sparrow or White been located within the archive leaving it unclear how much work either man was engaged in at Hawksworth. Walter VI did though continue to improve his estate, appointing the architect Carr to modernise the hall in 1774, only a few years after he had designed Harewood House (Warleigh-Lack 2013, 290). Two decades after embarking on improvements, Walter VI inherited Farnley Hall (1786) and, as stipulated in the bequest, changed his name to Walter Ramsden Beaumont Hawksworth [Fawkes] and made Farnley the principal family home (Speight 1905, 295).

1787 – 1899

When Walter VI Ramsden Beaumont Hawksworth [Fawkes] (1746-1792) left Hawksworth Hall in 1786, it marked the end of around five centuries of occupation by the Hawksworth family and the start of a 133 year period of the hall being occupied by tenants.

A survey book of 1788 (plan missing) (LUSC DD161/11A/7a) provides some insight into the landscape shortly after Walter VI vacated Hawksworth Hall (Figure 5). It describes areas of plantation east and west of the hall, and park (Hall Croft) to the south with few trees (approx. 3% of the area was plantation). The stated area of the two plots that are listed as Hall Croft suggest that the wall running north-south through the park on Sparrow’s plan (1768) remains in situ. Indeed, the inclusion of the park as a number of named plots suggests that the site was still divided into distinct areas (Hall Croft 140 and 141, Tofts 142, and Greenhouses 143), rather than open parkland. Furthermore, the area is referred to as ‘James Deane’s Farm’ which is somewhat at odds with an ornamental park.

William Mounsey of Otley prepared an undated estate plan for Walter Fawkes (LUSC DD193/10) between 1768 and 1825. Given that Walter VI Fawkes’ son, also a Walter and last of that name to be seated at Farnley, died in 1825 and one William Mounsey is listed as a land surveyor in the Baines’s Directory and Gazetteer Directory of 1822 for Otley, it is likely that the plan dates from the latter end of the range, probably c. 1820s. Corresponding with the description given in the 1788 survey, the plan shows two plantations east and west of the hall, the former with a drive that, in part, aligns with the two tree-lined avenues of 1768. This plan confirms the completion of east-west carriageway providing access to the front of the hall, whilst the absence of the south parterre suggests that this was installed after the 1820s. It confirms that the walled kitchen garden has by this time been moved from the northeast side to the northwest corner of the park which otherwise appears open with a few small clumps of trees, the largest one being south of the fishpond. Notably, the bisecting north-south wall remains in situ in Hall Croft.

The tithe (WYAS) and estate maps of 1848 (private collection) reveal the absence the drive within the east plantation, which was present c. 1820s, and, for the first time, a formal south front garden. Timothy Horsfall was the tenant living at Hawksworth Hall during this period 1833–1877. He may have been responsible for the development of the formal geometric designed parterre south of the hall that is extant. Horsfall is known to have been the president of the local Menstone Horticultural and Cottage Gardeners’ Society and to have hosted a visit by the Idle Wesleyan Chapel, who enjoyed ‘a pleasant day in the park and grounds’ (Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer 24th July 1869; Bradford Observer, 25th July 1867). He may well have continued to develop the gardens in the fashion of the time. These two maps also reveal that by this time the wall bisecting Hall Croft had been removed though planting in the park remained sparse with one copse on the east boundary and a few specimen trees.

1899 -1919

The hall and gardensIn 1898/9 the parkland and garden were split between two tenants; Duncan Law took on the tenancy of the hall and immediate grounds whilst The Bradford Golf Club entered into a 20-year lease of c. 100 acres of parkland i.e. Hall Croft.

By this time the estate, including the hall, was falling into a state of considerable disrepair. The chartered surveyors and auctioneers Hollis and Webb were instructed in May 1900 by Frederick Hawksworth Fawkes to evaluate the Hawksworth estate (Laurence 1991, 96). Farmhouses and their outbuildings were recorded as old and rundown with the tenants living in unsanitary conditions whilst poor drainage was affecting agricultural land. Houses in the village urgently required repair to the extent that the appearance of the village was affecting the value of the estate. Only through the extensive alterations and improvements made by Law was the dilapidated hall rescued. With a series of recommendations, Hollis and Webb suggested the estate be put up for sale with a reserve of £60,000. An auction was arranged, but for reasons that are unclear Fawkes did not go ahead with the sale at this time.

Law was the tenant of Hawksworth Hall during the period 1899-1919 and later the owner from 1919 until his death in 1923. There can be no doubt that Law was a keen gardener, with a particular interest in roses. Throughout the 24 years that he resided at Hawksworth, he supported regional gardening societies, submitted entries to local horticultural shows and accommodated several garden visits.

As Vice President of the Saltaire Rose Society he hosted visits by the Society in 1904 and 1906. Members viewed the ‘extensive rosary and herbaceous garden’ and the ‘thousands of roses, sweet peas etc.’. Great acclaim was given to the ‘lovely delphiniums, campanulas, Peruvian lilies’ and ‘a fine border of Canterbury bells’ (Shipley Times and Express 19th August 1904; 27th August 1906). The most likely site for this herbaceous garden and rosary is the area southwest of the hall. Visiting members of the Bradford Paxton Society were equally delighted with the gardens when they visited in 1908 and 1909. They were ‘conducted round extensive grounds by Mr. Duncan Law, who named the newest kinds of roses, sweet peas and herbaceous perennials’ (Shipley Times and Express, 17th July 1908; 27th August 1909).

In July 1904, Law was presented with a sterling silver medal from the National Rose Society by the Saltaire, Shipley and District Rose Society for a Premier Bloom with the rose ‘Bessie Brown’. Similarly in 1910, only four years after rose ‘William Shean’ was introduced into the UK, he was awarded a National Rose Society’s bronze medal for the bloom (Wharfedale & Airedale Observer, 19th August 1910). At the same show Law was bestowed with 1st class and presented with a silver rose bowl for twelve hybrid tea blooms (The Gardener’s Chronicle, 6th August 1910). His gardener of two decades, [John] Johnson, was also acknowledged in the news reports. Law was clearly at the forefront of rose cultivation. In addition to the rose ‘William Shean’, others for which he received praise were also recent introductions; the hybrid teas ‘Bessie Brown’ (bred 1899), ‘G [George] C Waud’ (1908) and ‘Hugh Dickson’ (1905) (Wharfedale & Airedale Observer, 19th August 1910).

In additions to those for roses, trophies continued to be awarded to Law throughout the period that he resided at Hawksworth including, in 1913, a prize at the Menston Flower and Vegetable Society for perennials (Leeds Mercury, 28th July 1913). The gardens at the hall were however, not restricted to prize winning flowers, with the Bradford Weekly Telegraph (17th August 1917) reporting a giant ‘Ponderosa Red’ tomato weighing in at 1 lb 9 ½ oz, with a circumference of 17 inches. Again, the head gardener, Johnstone was acknowledged (ibid.).

The park (Hall Croft)In October 1898, members of the Bradford St Andrew’s Golf Club on Baildon Moor approved a scheme to see a new golf course developed on land that was part of the Hawksworth estate. Fawkes leased c. 100 acres, principally Hall Croft, to the golf club for a period of 20-years at a rental of £1 12s 6d per acre (Richardson 1991, 13-4). A new course was laid out by W.C. Gaudin, a club house built (formally opened November 1900), and the Bradford Golf Club opened 1st May 1899 (Beaumont 2013; Richardson 1991, 13-4). A description from that time depicts moorland of gorse and heather with few trees (Beaumont 2013). Given that the course was opened for play within 6 months, it is likely that this early description provides a reasonable picture of the late 19th century park.

During World War I, sheep were allowed to graze the course and 35 acres were used for agriculture; 10 acres of rough being ploughed and 25 acres used to grow hay (Richardson 1991, 21).

On the 28th of July 1919, the estate was sold through auction by Dacre and Son of Otley as a series of separate lots, realising a value of £17,500 (Laurence 1991, 99). Prior to the auction, Law privately purchased the hall for £9,000 and three farms were sold to High Royds Hospital (West Riding County Council) for £12,500 (Laurence 1991, 99). Negotiations with the Bradford Golf Club started in 1919 with Fawkes offering the land for sale at £9,000, but after some negotiation the golf course and a property in the village, which the club had been leasing, were purchased in 1920 for £5,500 (Richardson 1991, 21).

Later history after 1920

The hall and immediate gardenLaw died in 1923, only five years after purchasing Hawksworth Hall. The estate was then acquired by Edgar Gaunt and used a private family residence for the next 32 years (Laurence 1991, 31; Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 14th April 1923). Little is known of the gardens during this period beyond the description prepared by the auctioneers Hollis and Webb in 1955 for the sales brochure (LLHL Hollis and Webb 1955). This described the terrace and formal garden to the front of the hall. The walled kitchen garden and surrounding grounds south of the public highway (c. 3 acres) included a good number of fruit trees, glasshouses and a potting shed within the walled area. Additional planting in the form of a lawn, shrubbery and a strip of arable land lay on the external south, east and north sides of the walled garden. Included within the sale were plantations to the east of the house with the main access drive, the meadow Guiseley Seat, north of the hall outbuildings, and finally, plantations to the west (now the publicly accessible Hawksworth Wood).

During the period from the hall first being occupied by a residential school (1955) to the present day nothing is known of the gardens, beyond an attempt to sell the timber from Hawksworth Wood (see below).

Golf courseThe purchase of land previously referred to as Hall Croft in 1920 by the Bradford Gold Club marked the start of a period of extensive course improvements. In 1919, Harry Colt and Alistair Mackenzie were consulted on possible improvements (Richardson 1991, 21). Few if any of their suggestions were implemented. A drainage system was, however, instated throughout the course at this time. Soon after in 1922, W. Herbert Fowler and Tom Simpson, leading figures in golf course design, were invited to reevaluate the course. A major redesign was undertaken with Frank Harris Bros. Ltd carrying out the work. The new course was opened for play in August 1923 (Richardson 1991, 23).

The original course of 1900 and even that designed by Fowler and Simpson in the 1920s featured open moor with few trees, a terrain that would persist for many years. More recently, a major programme of tree planting has radically altered the character of the course and today there is an abundance of mixed tree planting across the course.

Location

Hawksworth Hall is located next to the village of Hawksworth, 1 mile west of the town of Guiseley and 13 miles northwest of Leeds.

Area

The historic area of the hall, gardens and parkland was 103 acres (41.7 hectares).

Boundaries

The northern boundary runs from SE 16573 41960 to SE 17158 41733, then south along Willow Lane SE 17259 41574 to SE 17021 41008, west to SE 583 41185 along the southern edge of Hall Croft (Bradford Golf Club), north to SE 16678 41639, including the extant walled garden, west along Hawksworth Lane to SE 16483 41812 and north to SE 16573 41960 along the footpath on the west side of Hawksworth Wood.

Landform

Hawksworth Hall lies at 210 m (688 ft). The plantation to the west (Hawksworth Wood) is the highest point of the site at 231 m (756 ft), dropping to 160 m (525 ft) at the lowest point of the site at the southern edge of Hall Croft.

The hall is built on Millstone Grit overlaid with sedimentary deposits of Till, Devensian – Diamicton. Hawksworth Wood is located on Rough Rock Flag – sandstone. The southern part of the estate, Hall Croft lies on Pennine Lower Coal Measures – mudstone, siltstone and sandstone and Rough Rock – sandstone overlaid with superficial deposit of Till, Devensian – Diamicton. The soil across the estate is slowly permeable seasonally wet acid loamy and clayey soils.

Setting

Located in the northeast corner of the South Pennines area, Hawksworth Hall is positioned on an elevated land ridge forming the southeastern tip of Hawksworth Moor with the Wharfe Valley to the north and views south towards Gill Beck and the Aire Valley beyond. The area is characterised by open moorland plateau dissected by small fast-flowing streams and broader valleys of the Aire and Wharf with pastures and meadows within the fertile valley floors.

Entrances and approaches

A footpath linking the front terrace of the hall and Hawksworth Lane

A path flanked by ornate gate piers, as depicted by Buck in his sketch of Hawksworth Hall c. 1720 and in the watercolour by Daw or Dale c. 1768 (Laurence 1991, 48) has been removed, probably at the time the ha-ha was installed c. 1768.

Courtyard to the west of the hall

An open area, possibly a courtyard, is shown immediately west of the enclosed south front garden on the survey of Hawksworth Hall prepared by Sparrow in 1768 (LUSC YAS/DD/193/8). Access to this area was direct from the public highway running east-west in front on the hall, the current day Hawksworth Lane. By c. 1820s this courtyard and entrance from the public road had been replaced by garden (LUSC DD193/10).

East-west carriageway from Hawksworth Lane

The east-west carriageway running across the front of the hall was installed between 1768 and c. 1820s. It is likely that it dates from the earlier part of this period when extensive alterations within the grounds were being undertaken, c. 1768. In addition, there was separate vehicular access adjacent to the west entrance of the carriageway providing discrete access to the outbuildings and rear of the hall. Today, vehicular access appears limited to the east entrance of the carriageway terminating at the hall (Figure 6), whilst the extant west entrance seems restricted to pedestrians. The access route to the rear of the Hall and outbuildings remains available.

The National Heritage List for England (NHLE) register describes a pair of sandstone ashlar gate piers at the east entrance of the carriageway dating from c. early 18th century [Grade II, NHLE no. 1262971]. Rusticated with chamfered plinths and moulded caps and urn finials (the latter thought to date from a later period), are described in the NHLE record (Historic Englanda). The urn finials are at present absent.

Principal buildings

Hawksworth Hall [Grade II*, NHLE no. 1251067]

An architecturally complex building of course dressed sandstone and stone slate roofs. The original hall and cross wings lie on an east-west axis with an added hall range to the east and two cross-wings to the east of this. The earliest parts probably date from the early 16th century with alterations in the 17th century; substantial additions being made in the decade c. 1660 -1670. Further alterations were made in the 18th century, with John Carr being known to have worked at the hall in 1774 (Historic Englandb; Warleigh-Lack 2013, 294).

Outbuildings to the rear of the hall

Three outbuildings of substantial size have been depicted on various maps and plans to the rear of the hall, with specific reference being made to a barn, stables and kennels. The barn c. 1611 takes the form of an extensive building northwest of the hall (building extant but condition unknown, possibly converted into housing). The exact location of the stables is unclear with White labelling all three outbuildings on his 1768 proposal as ‘stables’. It is likely that the stables were within the barn complex and/or a second smaller building directly north of the hall. This latter structure is seen on maps and plans up to 1889-91 (OS 6-inch surveyed 1889-1891, published 1895) but absent from those prepared in the 20th century. The third and smallest of the three structures lies north of the barn and is identified as kennels on an undated map of the village that includes a footpath through the park labelled to ‘Esholt Station’ (opened 1876) and Hawksworth School (opened in 1874) (LUSC YAS/DD161/11B/1). The earliest known recording of a structure on this site is the c. 1820s estate map (LUSC DD193/10). This building is at present thought to be in a ruinous state.

Gardens and pleasure grounds

South front of the hall

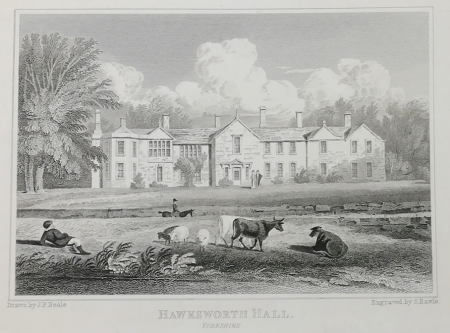

Buck’s sketch c. 1720 provides the earliest visual depiction of the garden in front of the hall. A balustraded terrace runs across the building with steps descending to an area enclosed by walls and railings (Wakefield Historical Publications 1979). There is no detail of planting within this area. The path that bisects the garden links the hall with the public highway and access is given via an ornate gate and gate piers. Whilst Sparrow’s plan of 1768 shows an enclosed garden, Daw or Dale’s watercolour c. 1768 depicts an open area with no terrace, walls or railings; only the path and gateposts remaining (Laurence 1991, 48; LUSC YAS/DD/193/8). It is likely that major alterations were being undertaken at that time, the two images capturing the changes. Neale’s drawing (1822) (Figure 7) and the estate map c. 1820s confirm that the enclosed south garden, the terraced area to the east (4.8.3) and courtyard to the west (4.8.2) had been removed by the early 19th century (LUSC MS 194/15/133; DD193/10).

With the sinking of the public road and the creation of a ha-ha c. 1768, open unobstructed views from the hall and south front garden were created across the park (Hall Croft). The effect is best illustrated in the drawing by Neale (1822) (Figure 7) (LUSC MS 194/15/133). This view from the hall across the park was retained until at least the first half of the 20th century; a photograph 1920-1950 reveals a panorama of a few scattered trees within the relatively flat, open landscaped area (by this time Bradford Golf Club) (HEAS WSA01/01/07730). Today those views are gone; the ha-ha wall now supports a substantial laurel hedge and the hall is entirely obscured from both the public road and the golf course.

By 1848, a rectangular garden with geometrically positioned flower beds, surrounded with an outer walkway and bisected by a central path had replaced the open south front (Hawksworth Hall Estate Plan, 1848). This layout remains extant, though photographs of the garden over the 80-year period c. 1907 – c. 1986 capture a simplification in the design of the planting beds. In the early part of the 20th century the terrace steps had white gates at the top of the flight and a pair of white urns at the bottom, both of which had been removed by the 1920s. The sales brochure produced by Hollis and Webb in April 1955 (LLHL Hollis and Webb 1955) show a simply planted glacis either side of the terrace steps. Corner beds adorn each of the two lawns with a central circular island and single rectangular bed adjacent to and midway along the bisecting path. Roses are included in the planting, whilst the side flanking borders support shrubs including rhododendrons. Satellite imagery suggests that the gardens remain relatively unchanged in layout today (Google Earth, 2021).

West of the hall

The courtyard depicted on Sparrow’s 1768 survey west of the hall and in front of the outbuildings had by the c. 1820s been replaced with an area of planting bisected diagonally by the east-west carriageway. By 1906, a portion of the trees and shrubs had been removed from a rectangular area adjacent to the road boundary and replaced, possibly with a lawn (OS 25-inch revised 1906, published 1908). A low-resolution photograph c. 1908 shows curving herbaceous borders of mixed planting including mature trees and an area of lawn. It is possible that this area contained Law’s rosary and many of his herbaceous borders.

East of the hall

In the earliest depiction of the garden east of the hall, Buck’s sketch c. 1720 reveals an enclosed area with three or possibly four terraces running east-west with the suggestion of topiary and railings or a claire voie (Wakefield Historical Publications 1979). Sparrow’s less detailed survey of 1768 shows a single raised terrace running from the back of the hall with steps at both the east and west end and an open enclosed area to the front (LUSC YAS/DD/193/8). The clearest depiction of this single terrace is seen in Daw or Dale’s watercolour c. 1768, where a high wall with steps at the west end is shown above a simple grass terrace and glacis.

By c. 1820s the terracing had gone, and the area was principally plantation, though a portion of the high terrace remained. Estimated to be 73 m long in 1847 (OS 6-inch first edition map surveyed 1847-8, published 1851), this wall had decreased to approx. 30 m in length by 1906 (OS 6-inch map revised 1906, published 1909) and shortly after, was all but gone. It is likely that much of the early terracing was removed during the extensive alterations c. 1768 when the east-west carriageway cut through the area and shrubs and trees were planted forming the east entrance carriageway to the hall which remains to the present day (Figure 6).

Kitchen garden

The first documented kitchen garden is identified as ‘old garden’ in the northeast corner of Hall Croft by Sparrow in his 1768 plan of the estate (Figure 3) (LUSC YAS/DD/193/8). By c. 1820 it had been removed and the new parallelogram shaped walled garden constructed (YAS/DD193/10). It is likely that these changes were undertaken soon after Sparrow completed his survey. Estate accounts indicate that John Nevil was paid for walling ‘… the wall adjoining the kitchen garden at 2s 6d per rood’ (July 1768) and John Cowgill ‘for cutting down and stubing 19 roods [approx. 114 m] of thorn hedge in the kitchen garden’ (October 1768), possibly within this new garden (LUSC YAS/DD/146 Box 28).

The earliest known depiction c. 1820s shows a quartered walled garden, paths lined with trees, probably fruit trees, and an outbuilding in the north wall, possibly a stovehouse (YAS/DD193/10). By 1848 the outbuilding had been increased in size, possibly to include the glasshouse which was damaged during a hailstone storm (Hawksworth Estate map, 1848). In May 1833, the Halifax Express reported that unusually large hailstones, in some cases three-quarters of an inch in diameter, had fallen during a particularly damaging thunderstorm causing extensive damage with upwards of 400 squares of glass being broken and most of the gardens being severely damaged. By 1891, further fruit trees are shown with a glasshouse now clearly present attached to the garden buildings in the north wall and an additional small glass structure, probably a frame, also within the walled garden (OS 25-inch revised 1891, published 1893).

The brochure produced by Hollis and Webb (April 1955) for the sale of the 31-acre site encompassing the hall provides the only known written description of the walled garden. The 2.026-acre walled garden had a good number of fruit trees growing against the high walls. Against the north wall were three heated glasshouses; 27 ft. 3 in. x 14 ft., 17 ft. 6 in. x 14 ft., and 27 ft. x 14 ft. To the north side of the wall was a stone-built potting shed, part of which was two storeys, and within a gas-fired Robin Hood boiler. Temporary storage was also available here. Within the walled garden there were cold frames with 13 lights and others with 6 lights. External to the walled garden at this time was an additional garden area: northeast (0.055-acres) with the potting shed; east (1.073-acres) including a path to the walled garden with planting on both sides, probably shrubbery, and Alders Well; south-west of the walled garden, probably a strip of arable land and a lawn.

In a survey of the walled garden undertaken in the late 1980s, George Sheeran identified an 18th century stovehouse within the garden building range in the north wall (George Sheeran, pers. comm.). The presence of the stovehouse, together with the thickness of the wall in this run and what appeared to be a chimney (albeit reduced), suggested the presence of a flue wall which is consistent with the 1955 particulars (LLHL Hollis and Webb 1955). The position of the then derelict 19th century glasshouse also corresponded with the glasshouse shown on the OS 25-inch revised 1891, published 1893.

The potting shed remains, in part at least, though the glasshouse range was demolished shortly after Sheeran completed his survey of the walled garden (Sheeran 1990, 201-2). Satellite imagery show that no internal structures or layout remain today whilst a crumbling section of the west wall highlights the precarious nature of this 18th century walled garden which has been turned over to industrial use.

Park and plantations

Hall Croft (the park)

Laurence (1991, 29) suggested that Hall Croft was transformed from a series of fields into a large informal park in the late 18th century. There is no known map depicting a separate field system, with the earliest of the park, referred to as Hall Croft, being Sparrow’s plan of 1768 showing an open area bisected by a single north-south wall. The 1788 survey book does, however, describe an area divided and in agricultural use. The north-south wall persisted until at least the c. 1820s but had been removed by the 1840s. The 1848 tithe map and estate plan, both show an open landscape of 72 a 0 r 1 p (0.3 km2) with few trees and a fishpond.

The park remained little altered to the point where its use was changed to the recreational sport of golf and even then, the changes were minimal in the early years of the course. Once Hall Croft had been leased to the Bradford St. Andrews Golf Club, a golf course was laid out, a club house built and The Bradford Golf Club opened to members 1st May 1899 (Richardson 1991, 14). A contemporary narrative depicts moorland of gorse and heather with few trees; a portrayal that probably provides a reasonable representation of the late 19th century park.

Following the purchase of the land from Fawkes in 1919, some improvements were made, but it is only in recent years that a major programme of tree planting has significantly impacted on the character of the landscape. A thick belt of trees on the northern edge of the golf course completely obscures views of both the public highway and the hall.

Plantations north and northeast of the hall

Sparrow’s survey of 1768 shows two tree-lined avenues running east–west in the area north and north-east of the hall. The upper avenue extends approx. 335 m (1,100 ft) and displays a distinctive circular copse of trees. Today the northern boundary wall follows the position of the avenue, indeed the northern edge of the circular copse of trees is outlined in the extant stone wall. The lower avenue runs approx. 207 m (681 ft) parallel with the terrace east of the hall and terminating at Guiseley Seat, the meadow east of the boundary of interest. The area between the two tree-lined avenues directly north of the hall is depicted as plantation with an open area to the northeast. This is reversed by the c. 1820s when the area north of the hall is shown open, and to the northeast is heavily planted with the lines of the avenues being remodelled into two drives; one follows the line of the upper tree-lined avenue and the second follows the line of the lower avenue, then turns south along the wall of Guiseley Seat and returns to the hall running parallel the east access carriageway. The first edition OS 6-inch map indicates that the drives following the line of the original tree-lined avenues remained in 1847/8, but the circular route had been lost. After this time, there is no cartographic evidence of these paths, but contemporary LiDAR hints that tracks remain below the tree canopy.

LiDAR and satellite images of the garden north of the hall reveal two features of interest. The first is a rectangular area SE 16843 41820. LiDAR hints at the feature, but it is a parch mark in the grass that is most distinctive (LiDAR DTM 50cm-1m; ESRI World Imagery). No feature is visible on the ground today. More intriguingly, LiDAR and the satellite image identify a rectangular feature adjacent to the north wall SE 16963 41775. On the ground this is clearly visible as a man-made, levelled area covered in grass. No structures corresponding to either feature have been identified on any map or survey viewed (from 1768) and their origin and purpose remain unknown.

Hawksworth Wood

An area of 7a 3r 9p and listed as plantation and pleasure grounds in the 1788 survey book is believed to be the modern day Hawksworth Wood (Figure 5). The c. 1820s estate map and subsequent OS maps also show plantation. In 1955 the woodland, which was described as 8.345-acre of plantation in the auction brochure, was bought with the hall by the National Spastics Association for the use of the hall’s residents. Soon after purchase, a timber survey described that antiquity of many trees, with a number of the mature trees said to be showing signs of decay (Bradford Observer, 25th October 1956). The evidence suggests that this area has remained largely undisturbed for an extended period of time. Ownership at the current time is unclear, but public access to the area is permitted.

Water

A fishpond (approx. 530 m2), first recorded in the 1788 survey, is located 72 m south of the south-east corner of the walled garden within Hall Croft (the park). It remains extant within the golf course.

Books and articles

Beaumont, J. 2013. Herbert Fowler and the Bradford Golf Club, Hawksworth: The Creation of a Little Known Jewel [on-line]. Available from https://golfclubatlas.com/in-my-opinion/herbert-fowler-and-the-bradford-golf-club/ (accessed 08.05.23).

Finch, J. 2020. ‘Place making: Capability Brown and the Landscaping of Harewood House, West Yorkshire’ In Capability Brown, Royal Gardener edited by J. Finch and J. Woudstra, 75-87. White Rose University Press.

Hearth Tax Digital. Tax Assessment West Riding of Yorkshire - Skyrack Wapentake, Hawkesworth, Lady Day 1672.

Historic Englanda, National Heritage List for England (NHLE). Gate Piers at the East Entrance to Hawksworth Hall, NHLE no. 1251067.

Historic Englandb, National Heritage List for England (NHLE). Hawksworth Hall, NHLE no. 1251067.

Hunter, J. 1830. The Diary of Ralph Thoresby (1677-1724), vol 1. Colburn and Bentley, London.

Laurence, A. 1991. A History of Menston and Hawksworth. Smith Settle, Otley, West Yorkshire.

Richardson, G.A. 1991. The Hawksworth Hundred, Bradford Golf Club 1891-1991. White Crescent Press Ltd., Luton, Bedfordshire.

Robertshaw, W. 1976. ‘Cameos of Local History’, The Bradford Antiquary 11 (new series 9), 254-274.

Sheeran, G. 1990. Landscape Gardens in West Yorkshire 16980-1880. Wakefield Historical Publications, Charlesworth and Co Ltd, Huddersfield.

Speight, H. 1905. ‘Hawksworth Hall and its Associations’, The Bradford Antiquary 4, 246-296.

Tupholme, A. 2015. Farnley Hall visit at AGM 2015, Yorkshire Gardens Trust Newsletter, Autumn 37, 10-13.

Turnbull, D. and Wickham, L. 2022. Thomas White (c.1736-1811) Redesigning the Northern British Landscape. Windgather Press, Oxbow Books, Oxford.

Wakefield Historical Publications 1979. Samuel Buck’s Yorkshire Sketchbook, Scolar Press, Ilkley.

Warleigh-Lack, C. 2013. John Carr of York and Hidden Architectural Histories (PhD thesis), Middlesex

Primary sources

Hawksworth Hall Estate Plan of 1848. Private collection.

Historic England Archive Services (HEAS)

WSA01/01/07730 ‘A View of Hawksworth Valley and Hawksworth Hall Gardens, 1920-1950’.

Leeds Local History Library (LLHL)

Hollis and Webb, 1955. Plans, particulars and special conditions of sale of the Hawksworth Hall Estate.

Leeds University Special Collection (LUSC)

MS 194/15/133 ‘Hawksworth Hall, Yorkshire. Drawn by J.P. Neale. Engraved by S. Rawle. London, 1822’.

YAS/DD/146 Box 28 ‘Fawkes of Farnley Collection’, 11th – 20th century.

YAS/DD161/11A/7a ‘Copy of a survey of Mr. Fawkes’s Estates in the township of Hawksworth made in the year 1788’.

YAS/DD161/11B/1 ‘Plan of Hawksworth Village’.

YAS/DD/193/8 ‘A survey of the grounds, roads, etc. adjoining Hawksworth Hall, Anthony Sparrow, 1768’.

YAS/DD/193/9 ‘Plan of Hawksworth showing proposed trees and garden, surveyor T. White, 1769’.

YAS/DD193/10 ‘A plan of the estate situate in the manor of Hawksworth…the property of Walter Fawkes Esq., undated, 19th century’.

YAS/MS1961 ‘Collection of photographs and postcards of Yorkshire places and places in other counties collected by Yorkshire Archaeological Society’.

Thoresby Society Archive (TS)

MS Box SD 1-17; SD17 Vellum-bound book 8x6¼in: An Account Book that has reference to Hawksworth – miscellaneous domestic and apparel items – 1728-9.

West Yorkshire Archive Service (WYAS)

‘Tithe Map for Hawksworth (1848)’ [on-line] http://wytithemaps.org.uk/leeds-maps/hawksworth (accessed 12.12.22).

Maps

Blaeu (1662-65) Ducatus Eboracensis Pars Occidentalis (the West Riding of Yorke Shire) map, 1662-65, Amsterdam [on-line]. Available from https://maps.nls.uk/view/104188177 (accessed 20.04.23).

OS 6-inch 1st edition, surveyed 1847-1848, published 1851.

OS 6-inch surveyed 1889-1891, published 1895.

OS 6-inch revised 1906, published 1909.

OS 25-inch revised edition 1891, published 1893.

OS 25-inch revised edition 1906, published 1908.

Figure 1 - Hawksworth Hall, 2005. cc-by-sa/2.0 - © David Spencer - geograph.org.uk/p/34302

Figure 2 - The boundary of interest outlined on the Ordnance Survey 6-inch revised 1906, published 1909. Features within the boundary of interest: 1, Hawksworth Hall grade II*; 2, south front garden; 3, ha-ha; 4, outbuildings; 5, plantation to the east of the hall; 6, east carriageway entrance, gate piers grade II; 7, west carriageway entrance and vehicular access to the rear of the hall; 8, Hall Croft, the park; 9, site of the old walled garden; 10, the extant walled garden; 11, fish pond; 12, Hawksworth Wood. National Library of Scotland CC-BY.

Figure 3 - Survey of Hawksworth Hall prepared by Anthony Sparrow in 1768 entitled ‘A survey of the grounds, roads and [illegible] joining to Hawksworth-Hall taken in the year 1768 by Anthony Sparrow’. Reproduced with the permission of Special Collections, Leeds University Library, Yorkshire Archeological and Historical Society Collection, YAS/DD193/8.

Figure 4 - A plan of Improvements for Hawksworth designed by Thomas White, dated 1769 (YAS/DD193). Reproduced with the permission of Special Collections, Leeds University Library, Yorkshire Archeological and Historical Society Collection, YAS/DD193/9.

Figure 5 - The descriptions of lots within the Hawksworth estate survey book of 1788 (plan missing) (YAS/DD161/11A/7a) were used to identify the probable locations and transposed onto the Ordnance Survey 6 inch- revised 1906, published 1909 map. National Library of Scotland CC-BY.

Figure 6 - East access drive of Hawksworth Hall looking west from the gate, 2012. cc-by-sa/2.0 - © Betty Longbottom - geograph.org.uk/p/3071500

Figure 7 - Hawksworth Hall, Yorkshire. Drawn by JP Neale and engraved by S Rawle (1822), London. Reproduced with the permission of Special Collections, Leeds University Library, MS 194/15/133.