North York Moors National Park

The earliest gardens at Hackness were associated with an Elizabethan manor house which may have had origins in the medieval manor which preceded it. As the home of Lady Margaret and Sir Thomas Posthumus Hoby from 1596 onwards, early pleasure grounds and a small park were added. The estate was sold to John van den Bempde in 1707, but it was only with the inheritance of his grandson, Richard Vanden Bempde Johnstone (later Sir Richard), in 1792 that the designed landscape we see today started to take shape.

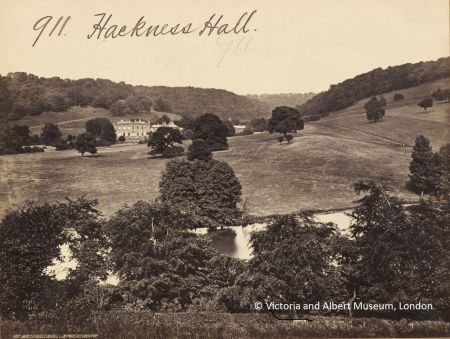

Nestling in a sheltered valley, Hackness offered the perfect location for a country seat. Sir Richard’s new designed landscape made full use of the advantages of the situation by ‘borrowing’ the surrounding woodland to provide the backdrop to a new park and laying out gardens on a south-facing slope which afforded fine views towards the River Derwent. York architects Peter Atkinson and John Carr were engaged to design a new hall and associated buildings which were completed by 1796. All traces of the pre-existing village and Elizabethan manor house were removed leaving only the church, with the villagers relocated to new cottages out of sight of the hall. By 1798 when the public road was diverted to make way for a small lake, the initial design was largely complete.

Although Sir Richard’s descendants were responsible for limited developments in the park and pleasure grounds during the 19th century, there were no significant changes to the overall design of the landscape. A lodge had been built by 1832 but there was little further building work after this date until the early 20th century when Walter Brierley was commissioned to re-design in the interior of the hall after it was destroyed by a disastrous fire in 1910. The Johnstone family continue to occupy the hall and the designed landscape surrounding it remains largely unchanged, although the gardens have been modified, the walled garden is no longer in use and there has been some limited replanting of woodland.

Estate owners

At the time of the Domesday survey the manor of Hackness was owned by William de Percy. Towards the end of the 11th century he granted it to Whitby Abbey, in whose ownership it remained until it was taken by the Crown at the dissolution (Page 1923, 528-32). In 1563 it was given to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, who sold it on to Sir John Constable of Burton Constable. The Constables were the owners until 1588-89 when the manor was purchased jointly by Arthur Dakins of Linton, the Earl of Essex (on behalf of his brother Walter Devereux) and the Earl of Huntingdon (Walter’s guardian) as an estate for Dakins’ daughter Margaret on her marriage to Walter (Moody 1998, xxi). On the death of both Walter Devereux in 1591 and her second husband Thomas Sidney in 1595, Margaret remained as the owner of the estate which continued to be her main residence after her marriage to her third husband, Sir Thomas Posthumus Hoby. Margaret predeceased Sir Thomas and since they had no children, the estate was inherited by a cousin, John Sydenham, when Sir Thomas died in 1641.

Ownership stayed with the Sydenhams until 1707 when, to relieve financial difficulties, Sir Philip Sydenham sold the estate to John Vanden Bempde, a wealthy London merchant of Dutch origin (Page 1923, 528-32). Vanden Bempde had no male heirs and under the terms of his will, the estate was put in trust on his death in 1726, to be inherited by his daughter Charlotte’s male offspring on condition that they should assume the name Vanden Bempde (NYCRO ZF 2/61). In 1744 Charlotte’s son George by her first marriage to William Johnstone, Marquess of Annandale, had already succeeded to his father’s title as 3rd Marquess of Annandale but changed his name to George Vanden Bempde in order to inherit his grandfather’s estate at Hackness (https://deedpolloffice.com/research/private-acts-parliament/1744-18-Geo-2-4 [accessed 31 January 2024]). However, one further condition of John Vanden Bempde’s will (ibid) was that the estate should not be inherited or managed by a lunatic, so when four years later George was declared insane, it appears that the estate was put back in trust. Estate accounts indicate that from at least 1779, Richard Johnstone (George’s half-brother through Charlotte’s second marriage to Lieut. Col. John Johnstone) was managing the estate on his brother’s behalf (NYCRO ZF 4/2/4). George eventually died without issue in 1792 and the following year Richard changed his name to become Richard Vanden Bempde and take up the Hackness inheritance in his own right (https://deedpolloffice.com/research/private-acts-parliament/1793-33-Geo-3-1 [accessed 31 January 2024]). Richard re-assumed his father’s name in 1795 when he was made a baronet, becoming Sir Richard Vanden Bempde Johnstone (https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/johnstone-(sometime-johnstone-vanden-bempde)-richard-bempde-1732-1807 [accessed 31 January 2024]), from whom the present owners are descended.

Key owners responsible for the development of the designed landscape and date of their involvement:

Sir Thomas Posthumus Hoby and Lady Margaret Hoby 1596-1641

Sir Richard Vanden Bempde Johnstone, 1st Baronet 1792-1807

Lady Margaret Vanden-Bempde Johnstone (widow of Sir Richard) 1807-1853

Sir John Vanden-Bempde Johnstone, 2nd Baronet c.1820-1869

Sir Harcourt Vanden Bempde Johnstone, 3rd Baronet and 1st Lord Derwent 1869-c.1916

Early history of the site

Hackness has its origins in the late 7th century with the establishment of a nunnery by St Hilda of Whitby, but apart from the remains of a carved cross which is now housed in the church nothing survives of this early period. It seems that a monastic presence may have continued, however, since the Domesday survey makes reference to ‘the land of St Hilda’ (Rimington 1988, 5). By the late 11th century a settlement at Hackness was well-established and although Domesday gives no pre-conquest owner, it is described in 1086 as a manor, recording eighteen households (Hackness plus the adjacent settlements of Suffield and Everley) with three churches and a priest. The manor is assessed as eight carucates, five of which were ploughable, plus woodland providing pasture measuring 2 leagues by 1 league (https://opendomesday.org/place/SE9690/hackness/ [accessed 20 October 2023]). William de Percy, who held the manor following the conquest, granted it to Whitby Abbey not long after the Domesday survey was completed (Page 1923, 528-32), and monastic occupation continued as Whitby maintained a cell or grange alongside the settlement (ibid).

Under the ownership of Whitby Abbey, the manor appears to have thrived with 55 households recorded in the 1301 lay subsidy along with at least two mills (Brown 1897, 109). By the time of the dissolution only four monks were living in the grange (NYM HER: HER 3206), but the manor appears to have been profitable. A 16th century description of Hackness, transcribed in 1709, portrays an established and well-appointed manor:

Hacknesse lyeth most pleasantly and near unto Scarborough surround on all sides with fair woods, hills and dales, pleasant springs, becks and an abundance of grass, corne, pasture, whereto belongs an old mansion place or manor house in metly repairation [reasonable state of repair], and hath Hall, parlour, great chamber, chapel, Bedchamber, closett, and many other Lodgings, two kitchins, a butterie, pantry, a Brewhouse, Mill, Barn, Bakehouse, Stables and Gilde house, with all other houses one cellarie whereto belongs a little Garden and Orchard. (NYCRO ZF 4/3/1 & 4/3/2).

This passage was written during the tenure of Sir John Constable (ibid) which indicates a date between 1563 -1579, and the use of the phrase ‘old mansion place’ suggests that the Elizabethan house had not yet been built and that the description refers to the medieval manorial complex. Since the Constables’ main residence was elsewhere, it seems probable that construction of the new manor house, depicted in a painting executed at the end of the 17th or very early 18th century (Figure 1), was during the ownership of Margaret Dakins (Devereux/Sidney/Hoby). It is likely also that the Hobys added to the pre-existing gardens referred to in the passage above and we know from the diary of Lady Margaret Hoby, written at Hackness 1599-1601, that they provided produce for the kitchen, herbs and flowers (Moody 1998, 194), and even a bowling green (ibid, 15). Sir Thomas Hoby also added a small park, described in 1696 as ‘a little Parke (walled round)’ (NYCRO ZF 4/3/10) and marked as ‘Great Park’ on an estate map from 1723 (Figure 2). It is likely that this park was created sometime after 1608 since it is not noted in an estate survey of that date (NYCRO ZF 4/3/3). Correspondence between Sir Thomas and the Attorney General in connection with a complaint made against him for unauthorised emparkment (ruled to be unfounded) suggests that it may have been added around 1618 (NYCRO ZF 7/6).

Little is known of the estate under the Sydenhams’ ownership or for much of the 18th century. Evidence from a 1723 survey (NYCRO ZF 9/1) indicates that the manor house and former park were tenanted at the start of the 18th century and this may have been the case for much of this period. The only change identifiable from historic estate maps is that the area marked as ‘Garden’ on the east side of the manor house on the 1723 estate map had been incorporated into the adjacent ‘Little Park’ by the time Outram produced a new map of the estate in 1774 (Figure 3). It is only with the inheritance of Richard Johnstone (soon to become Richard Vanden Bempde) in 1792 that major changes started to be effected.

Chronological history of the designed landscape

1792 - c.1804It is clear that from the outset Richard Vanden Bempde MP intended to make Hackness his country seat and to remodel the landscape into a fashionable country estate. His ideas may well have begun while he was managing the estate on behalf of his half-brother and it seems likely that the survey of the estate produced in 1774-5 (Figure 4 and NYCRO ZF 4/3/6) was commissioned by him in anticipation of coming into the inheritance. As early as 1792 he paid one of his tenants, John Gray, for ‘clearing the nursery ground and planting out young trees’ as well as a year’s salary for ‘superintending the new buildings’ (NYCRO ZF 4/2/4). A new survey and valuation of the estate was completed (based on the 1774 mapping), in which he was already identifying plots of land for construction of new houses to accommodate tenants who were to be evicted from the medieval village when it was demolished (NYCRO ZF 4/3/7). These may have been the buildings John Gray was to supervise. Work began almost straight away, perhaps boosted when he was made a baronet in 1795, so that by 1796 the major phase of building work had been completed.

His new Palladian-style country house is believed to have been designed by York architect Peter Atkinson, with the associated stables and outbuildings designed by John Carr. A walled garden was constructed to the northwest with an orangery built at its centre in around 1800, also by John Carr. Further new buildings were erected to the southwest and south of the walled garden, including Low Hall with associated outbuildings and a pair of cottages adjacent to the church. Low Hall could have been intended as a dower house, although census records show that it was occupied by the estate’s agent between at least 1851 and 1911. The new village was constructed about 1km to the south west of the old one, although a list of estate properties compiled in 1796 suggests that the houses of the medieval village were standing empty at this time awaiting demolition (NYCRO ZF 4/3/16). The new village occupied a prominent position, in view as the park was approached from the south, but it was out of sight from the new hall and grounds apart from a dovecote adjacent to the new keeper’s house which could be seen high on the slope above the village from the rides ascending to the woods behind the hall.

Once the initial building work was complete, over the next few years attention clearly turned to shaping the surrounding park. The former village and the Elizabethan manor house were removed leaving only the church. Around 1798 the public highway running south towards Ayton was moved to the west to make way for construction of the fishpond which was to occupy the view from the southwest facade of the new hall (NYCRO QSB 1800 13/1). Extensive water management works were undertaken to re-route the numerous local watercourses to avoid the immediate area around the hall and to feed into the new lake, and presumably also to supply the walled garden. By 1804 the initial plan for the new designed landscape was largely complete. Tuke’s map of the estate from this date (Figure 4) shows an expanse of lawn in front of the house with the gardens to the north of the public road linked by a bridge to those around the house. The wider landscape incorporated the surrounding woodlands with rides snaking through them and parkland in the valley bottom, although the estate map shows that the earlier field boundaries in the parkland had not yet been removed.

1807 - 1832On his father’s death in 1807, Sir John Vanden Bempde Johnstone was a child of only seven years so it was his mother, Lady Margaret, who must have been the driving force behind the early 19th century changes to the designed landscape. The hall was extended and its entrance modified in 1810, while the entrance driveway was moved to the east and an imposing new entrance gateway (Grade II, NHLE: 1296579) built at the roadside. Removal of the former entrance driveway allowed the creation of a terrace in front of the southwest facade of the hall which offered panoramic views across the landscape. The northern part of the lawn depicted on Tuke’s map (Figure 4), through which the original entrance drive had run, was also divided from the parkland to the south by the insertion of a boundary to create pleasure grounds closer to the house. Bigland, writing in 1812, refers to spacious and elegant gardens terraced into the slope overlooking the hall, and comments that:

The writer of this volume...must confess that in all his tours through different parts of Yorkshire, he has not seen gardens more finely situated, or in a more flourishing state, than those of Lady Johnstone of Hackness. (Bigland 1812, 372)

Work within the wider designed landscape also included construction of a park lodge on the eastern approach road, possibly to create the impression that the road was a private carriageway through the park, and replacement of the old Johnstone Arms public house (a building shown on the 1723 estate map) at the southern entrance to the park with a new building (Grade II, NHLE 1316140). Neither of these new buildings are mapped by Tuke but are shown on William Smith’s map (Figure 5) produced in 1832 while he was the agent for the estate. Cole writing in 1825 describes recent changes to the park which included as well as the new lodge, changes to the water courses and enlargement of the lake with ‘embellishment of the sides of the carriage-road, by plantations’ (Cole 1825, 79), the latter probably alongside the approach road from the south.

c.1832 - 1869Lady Margaret may have retained an involvement in the gardens until her death in 1853, but in adulthood her son also had an interest and continued to make changes on the estate. The 1st edition 6” Ordnance Survey map, surveyed in 1849, shows the pleasure grounds between the hall and the church to the west redesigned with island beds dotted through the former lawn (Figure 6). An ice house was built north of the road, just outside the pleasure grounds – not mapped by Smith in 1832 (NYCRO ZF 9/11), but appearing on the 1st edition 6” Ordnance Survey mapping.

Outbuildings built against the north wall of the walled garden had also been extended by 1849 and a testimonial provided by Sir John and published in the Gardeners’ Chronicle and Agricultural Gazette for February 13 1864 (160) indicates not only his interest in gardening, but that he had added at least one new glasshouse in 1861 supplied by Samuel Hereman of London. By 1849 a nursery had also been established to the west of the village. It is not clear whether this site might be the same as that referred to in the 1792 accounts (NYCRO ZF 4/2/4) but no nursery is marked on Tuke’s 1804 map.

Elsewhere on the estate building work in the 1850s and 1860s included fine new residences for his eldest son (Hackness Grange at the west end of the estate village and outside the park, Grade II NHLE: 1148854) and an imposing vicarage for his nephew the Reverend Charles, replacing an earlier parsonage. The latter is mapped on the 1st edition 6” Ordnance Survey map and was demolished to make way for Hackness Grange. The vicarage has a prominent position opposite the walled garden commanding views over the church to the park and down the valley to the south and is the first building to be seen from the bridge over Lowdales Beck on the approach to the hall from the south and west. Former field boundaries in the valley bottom parkland may also have been removed during this period as they are no longer mapped on the 1849 Ordnance Survey map.

1869-1914Sir John’s successor, his son Harcourt, was to become the first Lord Derwent in 1881 (Page 1923, 528-32). Ordnance Survey mapping shows no significant changes to the general layout of the designed landscape, but under his ownership the gardens continued to evolve and flourish. By 1890 the area in front of the southwest facade of the hall had been enhanced by the addition of a fountain (Figure 7) while a summerhouse had been built in Hilda Woods to the north. Ordnance Survey maps also show that further glasshouses were added in the walled garden. A second nursery was established on land south of the river opposite the village (Ordnance Survey 2nd edition 25” map, surveyed 1910). In 1910 a catastrophic fire devastated much of the interior of the hall, but it was rebuilt the following year within the original facades to a design by Brierley (NHLE: 1148859). A new cottage, probably to accommodate domestic staff, appeared adjacent to the stables complex during this period and is mapped for the first time on the 1912 edition of the 25” Ordnance Survey map (surveyed in 1910).

Later historyAlthough throughout the twentieth century successive Lords Derwent occupied the house as their country residence, the landscape saw no major alteration. By the time the 3rd edition 25” Ordnance Survey map was surveyed in 1926 the hall’s water supply and sewage system had been modified by the addition of a reservoir, sewage beds and a hydraulic ram, the latter possibly to improve the supply into the walled garden since another small reservoir is marked on the slope above the walled garden. The parkland around the hall remained largely intact while the pleasure grounds continued to be maintained as private gardens with some modification to layout and planting of beds, possibly to make them less labour intensive. In particular, the view from the hall terrace towards the northern gardens was opened up by the removal of some of the trees and shrubs alongside the perimeter walk.

Location

Hackness Hall is located 7.4km (4.6 miles) north west of Scarborough and 6km (3.7miles) north of the villages of East and West Ayton.

Area

The designed landscape at Hackness covered 183.4 hectares (453 acres), of which about 91 hectares (225 acres) were the surrounding and enhanced woodlands (Figure 8).

Boundaries

The designed landscape is bounded by the top of the steep wooded slopes of the surrounding valleys. To the east the boundary stops just short of the village of Suffield, at the point where the modern ‘Hackness’ village name sign is positioned. To the south the boundary was the southern and southeastern limits of Walker Flat Wood, Greengate Wood, Sheepstray Wood and Pepperley Wood. To the west and north the boundaries were at the limits of Hackness Head Wood, Loffeyhead Wood, Hilda Wood, Bellsdale Woods, Thirlsey wood, Merrick’s Wood and Crossdales Wood.

Landform

Hackness Hall is located in a valley bottom at the confluence of several small stream valleys which converge before joining the valley of the river Derwent to the south. Lowdales Beck and Crossdales Beck are the principal watercourses. Numerous springs arise at the base of the steep valley sides and drain towards the watercourses. The hall lies at 68m AOD and the gardens are laid out on sloping ground to the north which rises to 93m AOD. The parkland slopes gently southwards towards the Derwent and more steeply up the valley sides to 125-160 m AOD.

The bedrock geology underlying Hackness Hall and the valley bottom is sandstone of the Osgodby formation. This is overlain on the valley sides by a succession consisting of Oxford clay, Lower calcareous grit, limestone and calcareous sandstone of the Yedmandale member, and Hambleton oolitic limestone. The soils are principally freely-draining loamy floodplain soils with some freely-draining very acidic sandy and loamy soils in places and shallow lime-rich soils on the higher ground.

Setting

Hackness is within the North York Moors and Cleveland Hills National Character Area (https://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/2646022?category=587130 [accessed 1 February 2024]), and is part of the Limestone Dales Landscape Character Type in the south east of the North York Moors National Park (https://www.northyorkmoors.org.uk/planning/landscape-character-assessment/North-York-Moors-LCA-Update-FINAL-REPORT-December-2021-for-website.pdf [accessed 1 February 2024]). The dale is enclosed by steep valley sides but opens out to the south towards the Derwent valley where there are open views to the northern escarpment of the Tabular Hills. The valley sides are wooded and the parkland in the valley bottom is pasture.

Entrances and approaches

Southern approach from the innMain approach into park from south. The public road running north from Forge Valley turns to the east in front of the inn (now a house, Grade II NHLE: 1316140) to enter the park. Almost immediately the approach turns back to the north, climbing Red Hill and following the new route established in 1798 to make way for the lake. It appears from postcards printed in the early 1900s (private collection) that the original road was as wide as the modern road which now uses it. A retaining wall marks its western edge where it has been terraced into the slope, while the boundary of the park to the east is fenced. It is now a modern fence, but narrow paling is visible on a postcard from 1905 (private collection). A line of trees follows the road on the opposite side of the fence, including beech, lime and yew, and between the trees are the first views of the lake with the hall beyond as the road rises. The route passes the main entrance to Low Hall which is flanked by stone gate piers at SE 96768 90528 and then crosses the bridge over Lowdales Beck at SE 968 905 (Grade II, NHLE 1148858), described by List Entry as early 19th century but likely to have been built at the same time as the new road. From the bridge, the mid 19th century vicarage (at SE 968 907) occupies a view framed by trees (including a large lime tree adjacent to the southwest end of the bridge) before the walled garden, church and hall come in to view as the road turns to the east again.

Eastern approach and lodgeApproach from east was created by improving the pre-existing public road in early 19th century. The road descends the slope from the eastern limit of the park and as the ground starts to level out towards the valley bottom, the lodge is situated alongside it at SE 980 904. The lodge was built between 1804 and 1832, probably in the early 1820s, and may have been intended to give the impression that the road was a private driveway. The road is mapped as gated at the lodge and appears as such on late 19th century postcards (private collection). Still followed by modern road.

Hall entrances, gate and gate piers [Grade II NHLE: 1296579]Entrance driveway runs south from eastern approach road, passing through gateway at SE 972 906. Gate piers built c.1810, with wrought iron gates described in the listing as 20th century. Entrance replaced an earlier driveway further to west which left the road adjacent to the church. A secondary entrance driveway giving access to the stable complex runs to the east of the extant gateway.

Principal buildings

Old Hackness HallManor house built sometime between 1563 and 1595, probably during the late 1580s when the estate was purchased for Margaret Dakins and Walter Devereux (see 3.2). In the late 17th/early 18th century painting of the old hall (Figure 1), the manor house has the appearance of a multi-phase construction with several wings to the side of an Elizabethan core seemingly built in a different (and possibly earlier) style, which might suggest that the new house of the late 16th century incorporated elements of the medieval manor or monastic complex. An account of the manor written in 1696 describes ‘A large and strong house...built with freestone and slated’ (NYCRO ZF 4/3/10). From the painting in Figure 1 the new building appears to have included an inner and an outer courtyard, with an entrance into the outer courtyard through a gateway in the west side. The manor house along with its associated service wings, outbuildings and gardens are depicted on the 1723 estate map (Figure 2).

Hackness Hall [Grade I NHLE: 1148859]Built c.1795 to a design by Peter Atkinson (snr). New entrance and extensions added in 1810. Interior remodelled by Brierley after a fire in 1910.

Stable block [Grade II NHLE: 1316119]Stables, carriage sheds and workshops to the immediate southeast of Hackness Hall. Built c. 1795 and believed to be by John Carr.

Barns [Grade II NHLE: 1172725 and 1148860]Built c.1795 to the immediate south and east of the stable block. The List Entry indicates that the latter is an unusually early example of a Dutch barn.

Low Hall [Grade II NHLE: 1316139]Built within the park at SE 96822 90539 with direct private access into pleasure grounds across a low stone bridge over the beck. Possibly intended as a dower house, although the death of Sir Richard Vanden Bempde while his son was only a child meant that it was never occupied as such. Shown on Tuke’s 1804 estate map. Adjacent outbuilding with remains of sawmill [Listed Grade II NHLE: 1148819] has a pump with a lead plaque dated 1799 so Low Hall is likely to have been built between 1795 when the main hall was built and this later date.

Orangery [Grade II NHLE: 1296601]In the centre of the walled garden at SE 96916 90662, commanding views to the south towards Forge Valley and the Tabular Hills escarpment, with the church in the foreground. Built c. 1800 to a design by John Carr.

Icehouse [Grade II NHLE: 1168083]Built in a hollow to east of pleasure grounds north of road at SE 97087 90629 alongside Kirk Beck. Described by Listing as early 19th century, although not mapped before 1st edition 6” Ordnance Survey map.

BoathouseLocated on east side of fishpond at SE 96920 90247. Appears for the first time on the 1st edition 6” Ordnance Survey mapping. A modern timber boathouse exists at this location.

SummerhouseLocated on the west side of Hilda Wood at SE 97039 90979 adjacent to a ride. The clearing survives and a possible earthwork platform (much degraded) but nothing of the structure. Built in the second half of the 19th century and depicted for the first time on the 1st edition 25” Ordnance Survey mapping surveyed in 1890. Views would have been across the park to the plateau of Suffield Heights as well as down into the narrow valley in which it was located.

Dovecote [Grade II NHLE: 1148853]Located at SE 96483 90127 to the immediate east of the new keeper’s house and built in the 1790s as part of the new village. Occupies a prominent position in views from the rides in the southern park and woodlands.

Gardens and pleasure grounds

Late 16th-early 17th century gardensThe gardens referred to in Lady Margaret Hoby’s diary included a walled enclosure on the south side of the house of 1r 20p in size (0.1 ha), depicted on the painting in Figure 1 and the 1723 estate map in Figure 2 and confirmed by the 1792 survey which itemises ‘a garden within the walls’ (NYCRO ZF 4/3/7). Both the painting and the map also show an enclosure on the north side of the house containing a building, confirmed by the 1723 survey to be a dovecote (NYCRO ZF 4/3/4). A further area of 1a 2r (0.6 ha) is marked ‘Garden’ on Figure 2 on the east side of the house, as well an orchard of 3r 17p (0.3 ha) which may correspond to an area of trees on the broadly contemporary painting. The 1792 survey describes this parcel as orchard planted with apple trees (ibid).

Lady Margaret’s diary entries indicate that the gardens provided produce for the kitchen as well as having ornamentals. Particular plants mentioned include apples (Moody 1998, 11), raspberries (ibid, 196), and artichokes and a variety of roses which the sheltered conditions allowed to bloom until November in a particularly mild autumn (ibid, 194). The bowling green inferred from the diary entry for 7 September 1599 (ibid, 15) can be identified as being located on the east side of the house, since this area is still referred to as ‘Bowling Green’ in the estate surveys of 1774 and 1792 (NYCRO ZF 4/3/6 and ibid), although in the surveys the parcel extends into the area of former park to the south of the manor house as well as to the east. A small structure depicted in the area marked ‘Garden’ on Figure 2 could have been a garden structure associated with the bowling, although there is no corroborating evidence for this.

To the east of the latter ‘Garden’, the 1723 map marks the 1a 2r (0.6 ha) ‘Little Parke’, probably created by the Hobys for recreation as pleasure grounds since it is not mentioned in a 1608 survey of the estate (NYCRO ZF 4/3/3), but by 1774 this had been incorporated into the same land parcel as the garden to the west (ibid) and together part of the area identified as ‘Bowling Green’. An ancient ash tree surviving in the southern pleasure grounds around the later hall (4.8.2) is likely to pre-date the designed landscape of the 1790s and may be located approximately on the boundary of the seventeenth century ‘Little Parke’.

A description of Hackness manor from 1696 describes the hall and surroundings:

Southern pleasure groundsThere is a pleasant Seat at Hackness, a large and strong House with a double Dove Coate, Granary and Brewhouses, all built with free Stone and Slated. There are 2 Orchards or Gardens with a Rivolet [rivulet] running through both of them wherein Fish may be preserved. There are 2 Corne Mills, one below and another above the house, which this Water turns. Another Rivolet runs through the Towne of Hackness stored with Crawfish and Trouts, both which run through a little Parke (walled round) into the River Derwent, which runs by the Towne Side. Hackness stands in a Vale surrounded by Hills which are planted with Oak and Ashwood and other Underwoods’ (NYCRO ZF 4/3/10).

Immediately surrounding Hackness Hall and separated from the road to the north and the churchyard to the west by a stone wall. On Tuke’s 1804 map (Figure 4) this area of the gardens consisted only of a tree and shrub lined walk running inside the boundary wall as far as the church and then continuing westwards alongside Kirk Beck as far as a small island at the north end of the fishpond which was accessed across a bridge. The walk also turned north to cross a small stone bridge (extant) into the garden in front of Low Hall. Smith’s 1832 map (NYCRO ZF 9/11) shows a larger area of garden had been created by the addition of a boundary running along the south side of the walk at its west end and then turning to the southeast towards the southwest corner of the stable block.

A terrace running along the length of the southwest facade of the hall appears to have been created from the original entrance drive as mapped by Tuke (Figure 4) and still affords panoramic views across the park to the landscape beyond; this may be the ‘terrace-walk commanding extensive views’ noted by Loudon (1825, 1079). Figure 6 shows that the southern pleasure grounds had been modified by 1849 to have extended shrubberies and a number of island beds studding the lawn in front of the west front of the hall. The Journal of Horticulture and Cottage Gardener for 5 August 1875 included a detailed account of the gardens which describes the island beds within the pleasure grounds as having roses and herbaceous planting in some, while others had bedding plants (117). Also described were pillars of roses and geraniums cascading from baskets set on pedestals. A photograph in the Historic England archive shows some of the island beds close to the hall, planted with a mix of shrubs and herbaceous plants in the early years of the 20th century (HEA PC09300).

A small rectangular outline mapped on the 1849 Ordnance Survey adjacent to the terrace across the front of the house is marked only as an earthwork on the 1st edition 25” Ordnance Survey map, surveyed in 1890 (Figure 7) and this appears to be no longer extant. It is not clear what this would have been. A fountain is shown in the lawn in front of the west facade of the hall on the 1890 Ordnance Survey map (Figure 7) which photographs in the Historic England archive (HEA BSM01/01/052) indicate originally had a statue of Hermes in the centre. In more recent times, after the 1958 1:10,560 Ordnance Survey map had been produced, the southern part of the lawn was re-defined into a square area, bounded by a sunk fence on its south and west sides and this survives now.

Other more recent developments included continuing the line of the terrace as a path running to the northwest and removing some of the trees and shrubs lining the perimeter path to open up views across to the northern pleasure grounds from the terrace. This area of the gardens as they survive today still has some of the island beds in the northern area of lawn, which is also dotted with specimen trees of varying ages. Most of these are coniferous and their size suggests that some are likely to have been planted during the nineteenth century. A substantial specimen of a Douglas Fir is likely to the same as that mentioned in the 1875 Gardener’s Chronicle (117) which is said to have been 40 years old at that time.

Northern pleasure groundsA stone bridge with a central arch over the road and two smaller arches on either side at SE 97070 90612 (Grade II NHLE: 1316118) was constructed in the late 18th century as part of the original design to link the southern pleasure grounds around the hall with those to the north of the road. The road at this point is at a lower level than the gardens on either side and would not have been visible from the pleasure grounds. Cole (1825, 79) describes the bridge as planted with shrubs cascading over the sides. Two copper beech trees flank the southern side of the bridge and their size suggests that they may have been planted when the bridge was first built. From the bridge, a level path runs on a terrace towards the walled garden.

On Tuke’s map (Figure 4) the northern pleasure grounds are shown as a woodland garden with Kirk Beck flowing through it, possibly a small wilderness garden. By 1849 Kirk Beck had been modified to include a small waterfall and the tree cover had been reduced and more shrubs added. This area remains informal with mature trees and flowering shrubs, but it is not clear how old these are and how much of the historic planting survives. The icehouse is located at the east end of this part of the gardens and is currently screened and shaded by a number of large conifers, including yews, which appear to be at least 100-150 years old.

Kitchen garden

The late 16th/early 17th century gardens described above (4.8.1) included productive areas, which may have been located within the walled garden mapped on the south side of the manor house, since this is the only garden mentioned in the 1792 survey (NYCRO ZF 4/3/7). This early kitchen garden was replaced by a 1.5 ha (3.7 acres) square walled garden with brick walls, faced with stone on the outside to the south, east and west. It was laid out on a south-facing slope to the northwest of the hall as part of the original landscape design.

In the original design as mapped by Tuke in 1804 (Figure 4) the interior was subdivided by a brick wall with an orangery sited in the centre of it. Four buildings are shown against the inside face of the north wall, depicted as greenhouses on Smith’s 1832 map (NYCRO ZF 9/11). Two small external outbuildings are depicted on the west side. Outbuildings against the exterior face of the north wall were added at some point before 1832 and mapped by Smith, including the stone built gardener’s cottage. Bigland refers to spacious and elegant gardens terraced into the slope overlooking the hall, in which ‘The greenhouses etc display a great and splendid variety of plants and flowers, to which the southern exposure of the situation is extremely favourable’ (Bigland 1812, 372). Loudon also makes reference to ‘a green-house richly stocked with exotic plants’ (Loudon 1825, 1079).

By the time the 1st edition 6” Ordnance Survey map was surveyed in 1849 the walled garden had the form it retains today, with a third terrace which had been created at the lower end (Figure 6). A sun dial is mapped in front of the orangery and a circular basin or tank (presumably a dipping pool) on the upper terrace behind the orangery. The south-facing and west-facing walls in the southern two parts of the garden were lined with espaliers and fan-trained fruit trees, some of which survive. Further glasshouses or cold frames are mapped on the 1st and 2nd edition 25” Ordnance Survey maps, surveyed in 1890 (Figure 7) and 1910 respectively, including one outside the walled garden to the immediate north. At least one of the glasshouses or greenhouses is likely to have been a hothouse, its presence suggested by a small soot-surrounded opening visible in the north side of the north wall. The 1875 description in the Journal of Horticulture and Cottage Gardener (117) describes the walls of the kitchen garden being lined with apples, pears, plums and cherries in addition to seven glasshouses for tender fruit (peaches, nectarines and vines), ornamentals and bedding plants.

Park and Plantations

Seventeenth century parkAn area of 9a 3r (3.95 ha) depicted and labelled as ‘Great Park’ on the early 18th century estate map (Figure 2) extended south from the manor house and its associated gardens. Created by Sir Thomas Posthumus Hoby between 1608 and 1618 (see 3.2 for discussion of dating).

Northern parklandFollows the small valley around Crossdales Beck east from the pleasure grounds and extends into narrow dry valleys to the north up to the lower edge of the steep wooded slopes. Created as part of the landscaping in the late 1790s, although some former field boundaries are shown on Tuke’s 1804 map (Figure 4) which could indicate that a few land parcels had not been fully incorporated into the park at this date. A maximum extent of 13.6 ha (37 acres) is depicted on the 1st edition OS mapping surveyed in 1849 and remains the same today. Parkland trees are scattered through the valley bottom, most, if not all, of which appear too young to be original although a photograph in the Francis Frith collection does show trees in this part of the park in about 1877 (Figure 9). Several rides cross the area and extend up both the dry valleys and the steep slopes to the north. A dry stone retaining wall runs along the north edge of the road eastwards to just beyond the rear entrance to the hall’s stable complex.

Southern parklandArea to west and south of hall, plus areas south of road through the valley of Crossdales Beck and southeast into Crossdales, extending into the small dry valleys at the south eastern extent. It is limited by the lower edges of the steeply wooded slopes which surround it. As with the northern parkland, this area was created as part of the landscaping in the late 1790s and includes the area marked as ‘Lawn’ on Tuke’s 1804 estate map (Figure 4), which incorporated the early 17th century Great Park, as well as ‘Plain’ and ‘Brown’s Close’, with the new fishpond sited at the western edge of Tuke’s Lawn. These three areas survive largely as depicted in 1804 and are separated by sunken fences.

The depiction on Tuke’s 1804 map of former field boundaries at the southeastern end of the southern parkland may indicate that the park had not reached its fullest extent of 26.6 ha (72 acres) at this date, but it is likely to have done so by the time the park lodge was built alongside the road some time before 1832. Earthworks of the earlier manor house complex are visible between the fishpond and the hall and appear on the 1st edition 6” Ordnance Survey mapping, surveyed in 1849, along with several footpaths crossing the park. The narrow strip of land between the fishpond and the road to the west is planted with trees and shrubs and a line of closely-spaced beech trees turns to the southeast from its southern end to mark the southern limit of the park at this point. At least some of the trees in this area may be part of the original design and include lime (common and broad-leaved), beech (common and copper), yew and laurel, A few large conifers may have been additions later in the 19th century.

Bellheads Wood and Hilda WoodForming the backdrop to the walled garden when viewed from the south, these existing woods extended north from the northern gardens and pleasure grounds, to the east of the road up to Silpho. From at least 1608 these areas were being managed, described as coppice in a survey of that date (NYCRO ZF 4/3/3), and in 1792 (NYCRO ZF 4/3/7) they covered 45 acres (18 ha) managed in hand by the estate. The woodland was modified from the late 1790s onwards with additional planting and rides. Laurels survive at the southern end of Bellheads Wood and in Hilda Wood there are sweet chestnuts, while the conifers planted on the slopes immediately above the walled garden are likely to be 19th century.

At the southeastern end of Hilda Wood the 1804 estate map appears to depict a small clearing in the woodland at c. SE 973 907, from where there would have been clear views of the hall, church and the lake beyond, as well as over the pleasure grounds. The rides were constructed to snake up the steeply wooded slopes and along the narrow dry valley in Hilda Woods, labelled ‘Hilden’ on Tukes 1804 (and earlier) maps, where a ride is shown crossing the valley at its northern end over a small bridge. The 1st edition 6” Ordnance Survey mapping of 1849 shows the rides through Hilda Wood with trees lining one edge. A small number of mature beech trees alongside the ride on the western side of the valley may be survivors of these trees.

Many of the rides are still visible as narrow terraces while some of those in Bellheads Wood were later modified to form a new and less steep road up to Silpho which is now followed by the modern road. The late 19th century summerhouse in Hilda Wood depicted on the 1st edition 25” Ordnance Survey mapping was located adjacent to the rides on the west side of the valley. From Bellheads Wood the views were across the walled garden and towards the river Derwent to the south.

Bellsdale East and West Woods, Thirlsey Wood, Merrick’s East and West Woods, Northfield Wood and Crossdales WoodBorrowed landscape forming the northern backdrop to the eastern end of the park. These woods covered 61 acres (24.7 ha) in 1792 (NYCRO ZF 4/3/7). From at least the first half of the nineteenth century they were modified by the creation of rides or tracks. Tuke’s 1804 map shows one running along the bottom of Bellsdale, leading up onto the farmland beyond, but others through Thirlsey and Merricks West Wood are not mapped before 1849 when they appear on the 1st edition 6” map, lined with trees.

Pepperley Wood, Sheepstray Wood, Greengate Wood and Walker Flat WoodBorrowed landscape forming the southern backdrop to the park. These woods existed from at least the early 18th century as they are named on the 1723 map of the estate (NYCRO ZF 9/5) and they covered about 56 acres (22.7 ha) in 1792 (NYCRO ZF 4/3/7). At the east end they line the approach into the park. Tracks terraced into the slopes of Greengate and Walker Flat Woods lead out of the park but have the same appearance as those in the northern woods and may also have been constructed as rides, although they are not marked on the 1804 estate map. These routes afford views over the hall and pleasure grounds, south to the Derwent valley, west towards the keeper’s house with dovecote and northwest into Lowdales.

Hackness Head Wood and Loffeyhead WoodBorrowed landscape forming the western backdrop to the park and covering about 38.7 ha (95.6 acres), which includes 13 ha (32 acres) of pasture in Lowdales. The keeper’s house and adjacent dovecote are located at the southwestern end of Hackness Head Wood as mapped in 1804. Hackness Head wood was modified, probably from the late 1790s onwards, by additional planting which included sweet chestnut, yew, laurel and rhododendron as well as conifers. The conifers may be around 100-150 years old so probably represent later 19th century additions to the woodland within the designed landscape.

Water

FishpondSmall 2.1 ha (5.8 acre) lake, labelled as a fishpond on historic mapping, located at the lowest part of the park to the west of the hall and fed by Lowdales Beck and Kirk Beck at its northern end. Constructed in 1798 or soon afterwards as the road south from Hackness was diverted to the west in in order to create space for its construction (NYCRO QSB 1800 13/1). At its southern end the lake feeds into the water supply for Hackness mill, which on the 1849 Ordnance Survey mapping is depicted as running through a series of weirs and sluices. On Tuke’s 1804 map (Figure 4) a small circular island is shown at the lake’s narrow northern end where the two feeder streams run either side. On Smith’s 1832 map (NYCRO ZF 9/11) this appears to have been modified by the separation of the two watercourses and the creation of a mill race to take Lowdales Beck to the west of the lake (as Back Race) and down to the mill to the south. Tuke also depicts a footpath running around the lake and across to the island, but by 1849 the eastern stretch of the circuit had been removed, superseded by a number of paths crossing the park between the lake and the hall to the east. From the surviving western part of the lake circuit there are views across the park and to the hall. The boathouse is located on the lake’s eastern bank at its widest point.

Upper PondSmall water body to the north of the road north of the lake, depicted for the first time on Smith’s 1832 map of the estate (NYCRO ZF 9/11). Fed by Lowdales Beck and probably introduced to control both the flow of water into the main lake and down to the mill via a new mill race running to the west of the main lake, as well as the supply for the saw mill located to the immediate north of Low Hall. The 1890 Ordnance Survey map depicts a sluice at the southern end of Upper Pond and this survives on the north side of the bridge over Lowdales Beck, although the pond itself was drained sometime after its depiction on the 1952 Ordnance Survey map.

Kirk BeckWatercourse diverted as part of the late 18th century landscaping to run through the pleasure grounds north of the road before passing under the road and through a stone-walled channel around the southern perimeter of the churchyard and on into the north end of the fishpond. At the east end of the northern pleasure grounds Kirk Beck passes beneath two paths which are carried over the watercourse on small stone bridges. At SE 97010 90612 its line is interrupted by a small waterfall which is marked for the first time on the 1890 Ordnance Survey map, although the abrupt change in alignment of Kirk Beck depicted in 1849 suggests that it may have existed at the earlier date.

Roadside water channelRuns along the northern edge of the road from SE 97092 90617, at the point where the original course of Kirk Beck would have crossed the road, westwards along the outside edge of the walled garden and towards Lowdales Beck which it flows into. First shown on the 1849 Ordnance Survey map on which it flows into Upper Pond at its western end. Possibly constructed to manage excess water on the road which may have arisen from the flow from natural watercourses and springs not being fully diverted into the man-made channels. The channel has a shallow open profile and is cobbled with rounded pebbles, although these have been re-set in cement and edged with modern kerbstones. It has a constant flow of water and is a prominent feature of the modern streetscape.

Crossdales BeckA section of Crossdales Beck is a gently curving watercourse running along the contours from approximately SE 97376 90593 to its junction with Kirk Beck at SE 97109 90672. 18th century mapping depicts this section which is likely to have been diverted along the contours to create a leat to supply a mill with probable medieval origins. The watercourse is still flowing, although interrupted by a recent drainage cut, and there appear to be rounded cobbles lining its base which are similar to the channel which flows at the side of the road through the present village. The cobbles may be an improvement associated with the late 18th century landscaping.

Lowdales Beck/Back RaceRealigned to feed the fishpond on Tukes’s 1804 estate map, but by 1832 it had been dammed north of the road to form Upper Pond and channelled into a new mill race south of the road which ran to the west of and parallel to the western edge of the fishpond before rejoining the former course of Lowdales Beck after the mill supply had been taken off. On the 1849 Ordnance Survey mapping, this southern stretch of the former Lowdales Beck is renamed ‘Brown Beck’ and a weir and sluice are shown to control the mill supply. The new mill race is named ‘Back Race’ on the 1st edition 25” Ordnance Survey map, surveyed in 1890; it still carries water which runs in a stone-lined channel, meeting an overflow from the southern end of the fishpond.

Books and articles

Bigland, J. 1812. Beauties of England and Wales: or Original Delineations, Topographical, Historical, and Descriptive, of each County. Vol XVI. London, Harris, Longman et al.

Brown, W. (ed) 1897. Yorkshire Lay Subsidy. Yorkshire Archaeological Society Record Series Vol 21. Leeds.

Cole, J. 1825. Cole’s Scarborough Guide. Scarborough, John Cole.

Cole, J. 1832. Cole’s Scarborough Guide 5th edition. Scarborough, Todd.

Journal of Horticulture, Cottage Gardener and Country Gentlemen 1875, Vol XXIX, 116-118

Loudon, J C. 1825. An Encyclopaedia of Gardening. London, Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green.

Moody, J. 1998 (ed). The Private Life of an Elizabethan lady: the diary of Lady Margaret Hoby 1599-1605. Stroud, Sutton Publishing.

North York Moors Historic Environment Record (NYM HER). HER no 3205 and 3206

Page, W. (ed) 1923. A History of the County of York North Riding: Volume 2. London, Victoria County Histories, pp. 528-532. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/north/vol2/pp528-532 [accessed 20 October 2023]

Rimington, F. 1988. ‘The three churches of Hackness’, Transactions of the Scarborough Archaeological and Historical Society 26, 3-10.

Primary sources

North Yorkshire County Record Office (NYCRO)ZF 2/61 The will of John Vanden Bempde 1726

ZF 4/2/4 Account book for Hackness estate 1779-1792

ZF 4/3/3 Survey 1608 of Sir Thomas Posthumus Hoby’s estate

ZF 4/3/4 A field book for the manor of Hackness 1723

ZF 4/3/6 Survey and valuation of Hackness 1775

ZF 4/3/7 Particular and valuation of an estate in Hackness 1792

ZF 4/3/1 & 2 Survey of Hackness Lordship (mid 16th century) and 1709 transcription

ZF 4/3/10 The value of the several towns belonging to the manor of Hackness, 1696

ZF 4/3/16 List of messuages, cottages and sites of fronts collected in the parish of Hackness,1796

ZF 7/6 Correspondence concerning a case brought against Sir Thomas Posthumous Hoby for possible illegal emparkment,1618/19

ZF 9/1 1709/1723 Dickinson estate map

ZF 9/5 John Outram estate map 1774

ZF 9/8 John Tuke estate map 1804

ZF 9/11 Hackness Hills by William Smith 1832

QSB 1800 13/1 Order for the diversion of a highway in the township of Hackness 1798

Historic England Archive (HEA)FF98/00296 Photograph of 18th century painting of former Hackness Hall

PC09300 Photograph of gardens around north west corner of Hackness Hall, c. 1900-1905

BSM01/01/052 Photograph of fountain in front of southwest facade of Hackness Hall, c. 1920 - 1939

Francis Frith Collection (FFC)9550A Photograph of Hackness, the park c. 1877

Maps

Ordnance Survey 1st edition 6” map, surveyed 1849-1850, published 1852

Ordnance Survey 1st edition 25” map, surveyed in 1890, published 1892

Ordnance Survey 2nd edition 25” map, surveyed 1910, published 1912

Ordnance Survey 3rd edition 25” map, surveyed 1926, published 1928

Ordnance Survey 5th edition 6” map, revised 1950, published 1952

Ordnance Survey 1:10,560 quarter sheet SE 99 SE, published 1958

Figure 1 – Late 17th or early 18th century painting by an unknown artist showing former Hackness Hall and village. © Lord Derwent. Reproduced with permission from Lord Derwent.

Figure 2 - Map of Hackness manor by Joseph Dickinson produced for John Vanden Bempde in 1723 (NYCRO ZF 9/1). Reproduced with permission from the North Yorkshire County Record Office.

Figure 3 – Manor house and village depicted on survey of estate by John Outram produced for Marquis of Annandale in 1774 (NYCRO ZF 9/5). Reproduced with permission from the North Yorkshire County Record Office.

Figure 4 - Map of Hackness estate by John Tuke produced for Sir Richard Vanden Bempde Johnstone in 1804 (NYCRO ZF 9/8). Reproduced with permission from the North Yorkshire County Record Office.

Figure 5 – William Smith map of the Hackness Hills 1832 (NYCRO ZF 9/11). Reproduced with permission from the North Yorkshire County Record Office.

Figure 6 - Ordnance Survey 1st edition 6”, surveyed 1849-50, published 1854. National Library of Scotland CC-BY.

Figure 7 – Walled garden and pleasure grounds around hall shown on Ordnance Survey 1st edition 25”, surveyed 1890, published 1892. National Library of Scotland CC-BY.

Figure 8 - Extent of designed landscape outlined on Ordnance Survey 1st edition 6” map, surveyed 1849, published 1854. National Library of Scotland CC-BY.

Figure 9 – Francis Frith photograph of Hackness Hall, the park c.1877 (FFC 9550A), taken from northwest near Thirlsey Bottoms © The Francis Frith Collection.

Figure 10 – Francis Frith photograph of Hackness Hall and church c. 1881 (FFC 13952). Glasshouses at back of walled garden are visible to the left of photograph. © The Francis Frith Collection

Figure 11 – Francis Frith photograph of Hackness Hall c. 1878 (FFC 10801), showing entrance gateway and northwest facade. © The Francis Frith Collection

Figure 12 - Francis Frith photograph of Hackness Hall, lake and park taken from southwest. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London