While Thomas Knowlton does not qualify to be a true Yorkshireman, having been born in Kent, he nevertheless spent the majority of his long life in the county. Like many men of his age he was a polymath, endlessly fascinated by the world around him and developments in scientific learning. While his ‘day job’ was as head gardener at Londesborough, the estate of the Earl of Burlington in Yorkshire, he also found time for botanical experiments, archaeology, ornithology and the study of fossils. He also acted as what would now be described as a ‘garden or landscape consultant’ to neighbouring estates such as Everingham.

He was a prolific letter writer, many of which have survived today and are the basis for Blanche Henery’s comprehensive biography No ordinary gardener: Thomas Knowlton 1691 – 1781, published in 1986. His correspondents included many of the leading figures of the day such Sir Hans Sloane, president of the Royal Society and Peter Collinson, the renown importer of new plant material, particularly from North America. For a man with such good connections, surprisingly little is known of his early life. We do not know what his father did for a living (although one of his three brothers also became a gardener) and do not know the extent of his schooling. We also have to assume that his horticultural training occurred during his employment.

His first known position was as a gardener at Offly Place in Hertfordshire. There he had undertaken experiments for Thomas Fairchild to demonstrate plant reproduction, the results of which Fairchild presented to the Royal Society in 1720. Shortly after he started to work for one of the leading nurserymen, James Sherard. In 1725 he moved to one of the grandest estates in the country to be head gardener: Canon’s in Edgware, belonging to the Duke of Chandos. The following year he left to collect plants for Fairchild from Holland and Guernsey before moving to Lord Burlington’s estate at the end of 1726. By becoming gardener to Burlington, Knowlton was to start working for the creator of the most innovative garden in England at the time: Chiswick.

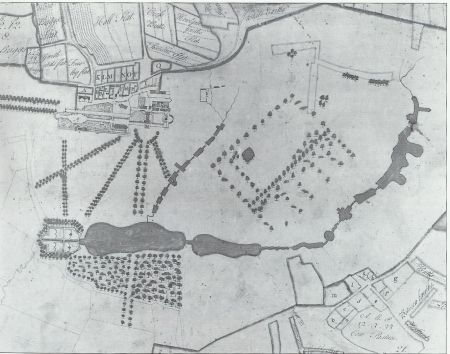

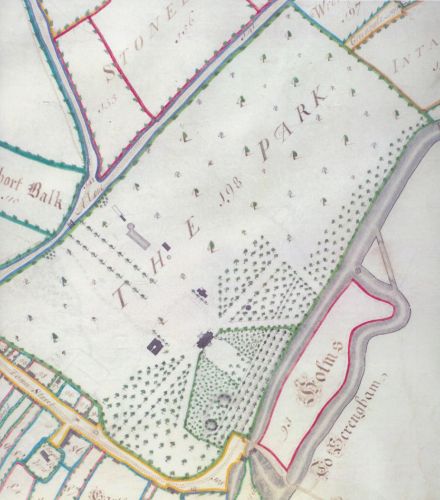

Little had been done to the formal gardens at Londesborough, laid out by Robert Hooke in the 1670s, when Knowlton arrived. The changes that had occurred by the time of the estate map of 1739, indicated Burlington’s desire to utilise the naturally attractive setting.

East Riding Archives, ref. DDX31/173

From the house at the top of one hill, the view was down to the lake below and onwards to the hill opposite. In contrast to Chiswick that had no such attractive vistas, Burlington did not need to add focal points such as buildings. David Neave argues that Burlington himself was the designer of the landscape at Londesborough, as he was at Chiswick. The extent of Knowlton’s input into the design is uncertain but given his horticultural expertise, it is clear that he would have influenced the plants used. One example is the turkey oak avenue, a novelty as they were only introduced into England in 1735. It is possible that Knowlton planted the turkey oaks that remain today.

Knowlton was only at Londesborough a few years before he was being consulted about other neighbouring estates. The earliest record we have is from a letter of 8 May 1727 when the estate manager at Everingham is considering him. This was not an uncommon occurrence at the time: a contemporary was Thomas Greening, gardener to the Duke of Newcastle at Claremont who went on to design gardens. However he remained at Londesborough unlike Lancelot 'Capability' Brown and others such as William Emes who became ‘professional improvers’.

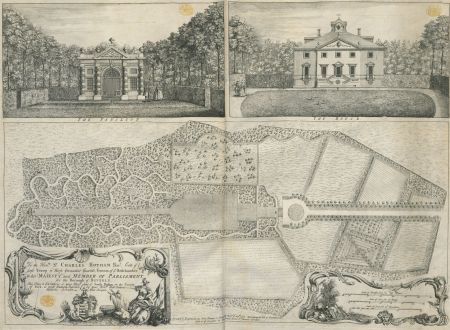

British Library: Maps K.Top.45.20.1.

The first estate where Knowlton was consulted was Dalton Hall, owned by Sir Charles Hotham. Hotham had a competent head gardener, John Scott, whom he employed in 1728, so Knowlton’s role could be described as an advisor. There are no records as to who did the design but a drawing by Rocque made in 1737 owes much to Londesborough and Chiswick.

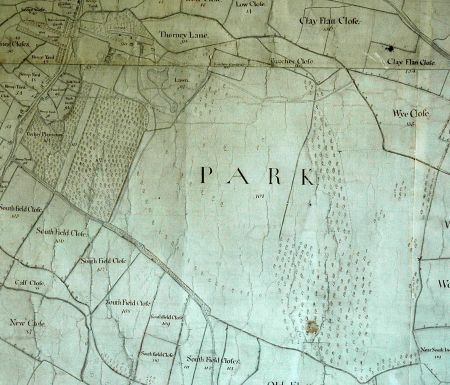

Thomas Willoughby, at Birdsall House near Malton, also consulted him in 1729 but it was at Everingham Hall however, four miles east of Londesborough, where he was occupied for many years. We know a lot about the work he completed here due to the letters that have survived between Sir Marmaduke Constable, the absentee owner and his Chaplain and de facto agent, Dom John Bede Potts. They discuss the progress that is made from 1730 until 1743 in the improvement of the estate. Knowlton and Marmaduke Lawson appear to have worked in partnership at Everingham. He is described as ‘Mr Lawson of Mowerby’ as he was the owner of Moreby Hall, 6 miles south of York.

Private Collection.

In the period from the end of 1730 to the last recorded payment on the 10th Dec 1743, Knowlton was paid at least £22 16s for his work at Everingham, excluding his supply of plants (about £30,000 in today’s money based on average earnings). Everingham was a long-term project for Knowlton in collaboration with Lawson and he may have been the designer, as no other candidates have come to light. If he was the designer, then his work here shows how his ideas changed. Although two formal avenues were planned, there was also, in the latter stages, some more naturalistic clumps planned and executed. This indicated a change in style, possibly following the ideas of Kent, which he would have seen at Chiswick that he often visited.

In his latter years, he worked at two more notable estates: Aldby Park and Burton Constable Hall. Henry Brewster Darley owned Aldby Park and on inheriting the house in 1743, Darley wanted to landscape the grounds. Three years later, we have a record of Knowlton working there. From a survey of 1746 and a bill from Knowlton dated 8th September of the same year, we can see the extent of the work that he completed at this time.

March 17th 1745/6 & March 24th & 25th 1746

‘To setting out & Levelling of ye West of the House’

March 24th & 25th

‘[To] planting of ye Filberts [Corylus maxima], Elmes, Privetts & ye Pruning all the Larches’March 31st & April 1st

‘To planting 1000 of Beech, 500 Hornbeam & 2000 of Birch & Levelling part of ye Court’

April 15th & May 19th

‘To Directions & Levelling the West Front...[and] Inspection’

May 22nd, 23rd, 29th

‘To Levelling the Court... and finishing’

9th June

‘To setting out the South Front’

16th & 23rd June

‘To setting out & Forming the Slopes’

3rd & 8th July

‘To setting out & Levelling of the Dove Court Avenue & Lawn Slopes’

For the above and the supply of 2000 Birch seedlings & 20 Wickin? Trees, Knowlton charged £8 7s 6d (about £12,000 in today’s money).

There is an undated and unsigned plan in the archives at Northallerton which given the layout is almost identical to the 1746 survey, one can speculate that this may have been Knowlton’s plan for the estate. There are meandering paths that lead to the old Saxon fort on the site, reminiscent of South Dalton and there is also what appears to be a walled kitchen garden to the bottom left. The slopes mentioned in the bill may have been inspired by the work Knowlton did on the terraces at Duncombe Park. Although Christopher Hussey attributes the design of the Duncombe terraces to Bridgeman, there are two references that connect Knowlton. The first is in a letter dated 27th February 1733/4 from Dom John Bede Potts to Sir Marmaduke Constable when he states that ‘ye person ytcommands ye labourers under Mr Knowltons directions is to go up to Mr Duncome (Thomas Duncombe)’. The next is a letter from Knowlton himself, dated 22nd October 1736: ‘I imagine I shall be sent for to Mr Duncombs…very soon they I know are Drawing to conclusion of what I had…seat…out’.

There are two more bills for work done at Aldby, the first from 24th August 1749 for £4 14s 6d refers to the following work:

27th October, 15th November & 14th December 1748

‘For Direction & Inspection & Setting out an Underground Drain’

20th December & 3rd January 1749

‘To Levelling & Setting the Pales’20th January & 17th February

‘To setting out & planting the Meanders’26th April

‘To Levelling with Directions’24th May

‘To setting out the Slope’

Aldby Park provides the most complete picture of Knowlton’s mature design style. Although there is some formality with straight avenues, the informal areas are now the most prominent, in particular his planting of the slopes. He is now using the natural landscape, just as he did at Duncombe, to create a better effect. However as the plans are not signed, we can never be sure that he was totally responsible for these.

The last place that Knowlton worked was the estate of Burton Constable in East Yorkshire, owned by William Constable, a keen amateur botanist. Constable had inherited the property in 1747 and devoted much time and expense on improving his property. He called in many designers (including latterly Brown) to make suggestions for improvements. Whether Knowlton was involved in changes to the landscape is not known.

We do know that however he planned and built the menagerie in 1761 that is sited at the end of the lake and a stove garden complex as confirmed by him in a letter in 1758:

‘I have Latly just finished 2 stoves with a Little Green house in ye middle of ym 206 feet Longe for Wm constable Esqr at Burton near Hull with fire walls 170 Long at ye each end of ym, all now I say compleat & finished about 6 week since & is ye greatest in it[s] kind of any I know.’

Knowlton’s first bill of 15 January 1757/58, is for ‘drawings concerning alterations at Burton: 10 pounds' could this be the plan in the Burton Constable archives that is undated? Elisabeth Hall dates this plan to post 1763 due to the inclusion of the menagerie. However this may be from an earlier date as it is in the same hand as the survey from 1755 and the menagerie shown could be merely part of the plan. It is also a significant sum (about £13,000 in today’s money) for just a plan of the menagerie.

Henery also speculates ‘that Knowlton assisted [William Constable] with the selection and planting of the various species [he] purchased’ from nurserymen such as Christopher Gray and Robert Blake. The latter supplied many hardy flowering shrubs such as Bladdernut trees, Spanish brooms, Bird cherries, ‘Spirea frutex’, laburnums, syringas given in the list in the Aldby archive.

Photo: Louise Wickham

Lord Burlington died in 1753 and Londesborough passed to the Duke of Devonshire, his son-in-law. Knowlton remained in East Yorkshire although he also worked at Chatsworth as ‘director of his Grace’s new kitchen-garden, stoves, &c.’ (recorded in a letter from 1762). This was the one built between 1760 and 1765 as part of the major remodelling of the estate by the 4th Duke, directed by Lancelot Brown.

Thomas Knowlton died in his ninetieth year and was buried in the churchyard at Londesborough: the memorial to him still stands today. It appeared that he never retired from his post as gardener at the estate, although towards the end of his life he was totally blind. His grandson, Thomas junior (1757 – 1837), carried on the family tradition, as he was a steward for the fifth and sixth Dukes of Devonshire.